Bayeux Tapestry, C11

Bayeux Tapestry, C11

St Augustine of Canterbury (d 604)

St Augustine of Canterbury (d 604)

Britain had already been a Christian land in late Roman times, but the Anglo-Saxons who flooded in during the C5 and C6 supplanted the old faith with their own belief in such gods as Tiu, Woden, Thor, and Frigg – Germanic deities after whom our weekdays are still named. Late in the C6, Pope Gregory the Great saw an opening to reassert Rome’s control of this far-off island, when the Christian daughter of King Charibert of Paris married the pagan King of Kent. To this end, he sent an obscure Benedictine monk called Augustine as a missionary. The mission was a shot in the dark, and nearly collapsed even before reaching Kent. Yet Augustine proved so adept on arrival that he converted the Kentish king, founded the English Church, built cathedrals at Canterbury and Rochester as well as St Augustine’s Abbey, and became the first Archbishop of Canterbury. Needless to say, this resounding success was rewarded by canonisation.

St Bertha, Queen of Kent (ca 565-post 600)

St Bertha, Queen of Kent (ca 565-post 600)

The fact that King Aethelbehrt of Kent’s wife Bertha was directly descended from Clovis, first king of all the Franks, goes to show what prestige Kent already enjoyed by the C6. She was a devout Christian, and shared her convictions with her pagan husband. Without her influence, it is doubtful whether Augustine could have met with a positive reception in England; indeed, Pope Gregory the Great even wrote to acknowledge Bertha’s piety. Although her son, the future King Eadbald of Kent, repudiated her beliefs, her daughter Aethelburg married a Northumbrian king and so carried Christianity further north. The oldest church in the English-speaking world, St Martin’s in Canterbury, was built for Bertha’s benefit, and she was made a saint for her role in re-establishing Christianity in England.

St Theodore of Tarsus (602-690)

St Theodore of Tarsus (602-690)

By 668, there had been one indigenous Archbishop of Canterbury. The second, Wighard, died before being consecrated, prompting the appointment of the most exotic yet: Theodore of Tarsus in Asia Minor, which was still ethnically Greek and within the Byzantine Empire. Theodore, who remained in the post for 22 years, was particularly assiduous. Having had a strikingly broad education in Constantinople and Rome, he opened a school at Canterbury intended to share such learning – which even included sacred music – with young men who would then proselytise as Benedictine abbots. He additionally undertook extensive reform of the English Church, which included fragmenting the Northumbrian diocese in the face of hostility from the Bishop of York. In 679, he intervened to avert war between Mercia and Northumbria. Having died in Canterbury at a venerable age, he was buried at St Augustine’s Abbey. His name may have spawned the Welsh name Tudor that was to cast a long shadow over English history.

St Sexburga of Ely (~640-~699)

St Sexburga of Ely (~640-~699)

Few people in history can have had as prestigious a family tree as Seaxburh (or Sexburga) of Ely. Her parents were King Onna of East Anglia and his queen Saewara; she married King Eorcenberht of Kent, grandson of the great King Aethelberht I and Queen Bertha of Kent; and she bore four children, of whom her two sons Ecgberht and Hlothhere became successive Kings of Kent, and her two daughters Ercongota and Eormenhild, both nuns, became saints. On her husband‘s death in 664, she temporarily served as regent. King Ecgberht granted her some land in Sheppey where she founded and directed Minster Abbey, having already founded one convent at Milton. After presiding over 74 nuns as Abbess, she succeeded her sister Elthelthreda as Abbess of Ely, Cambridgeshire around 670. According to legend, she had Elthelthreda’s remains disinterred for reburial in a new shrine, and found them uncorrupted. For this miracle, she emulated her four siblings by being canonised.

Odo, Archbishop of Canterbury (died 958)

Odo, Archbishop of Canterbury (died 958)

A century before Odo of Bayeux demonstrated that bishops are no angels, another Odo, or Oda, set a bad example. Probably born in East Anglia, and the son of a Danish invader, he repudiated his pagan background for a lucrative career in the Church. He was bishop of Ramsbury when, according to legend, he attended the battle of Brunanburh in 937 and miraculously restored Aethelstan’s sword after it was lost. Four years later, he was promoted to archbishop of Canterbury. Apart from annulling King Eadwig’s marriage, probably on dynastic grounds, and driving the queen into exile, he occupied himself codifying laws that among other things asserted the supremacy of the clergy, who were to be immune from taxation; anyone who dared say otherwise could literally go to hell. Although his fellow clerics gave him the epithet Odo the Good, and he was posthumously hailed a saint, poet Michael Drayton branded him Odo the Severe.

St Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury (~909-988)

St Dunstan, Archbishop of Canterbury (~909-988)

Dunstan from Wessex was a talented artist and silversmith, but above all a fine administrator. Already running and revitalising Glastonbury Abbey by 945, he was in and out of favour under several kings, including Aethelstan, sometimes effectively operating as prime minister. Having served as bishop successively of Worcester and London, he became archbishop of Canterbury in 959. He enjoyed great popularity, not least owing to folk tales of his repeated outwitting of the devil. He supposedly grabbed Lucifer by the nose with tongs; and he removed a horseshoe he had nailed on the devil’s foot only when the devil promised never again to enter a house sporting a horseshoe over the door – a supposed source of the tradition of the lucky horseshoe. Although (or rather because) such stories were unauthenticated, he was canonised. Monks on the make later claimed to have removed his lucrative remains from Canterbury Cathedral to Glastonbury, a claim Archbishop Warham disproved by opening his tomb in 1508.

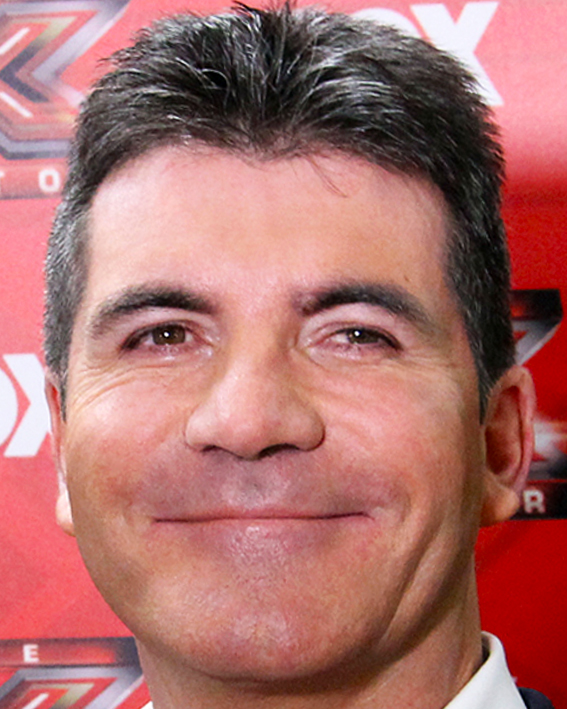

Stigand, Archbishop of Canterbury (died 1072)

Stigand, Archbishop of Canterbury (died 1072)

Since Stigand and his brother Aethelmaer, born in East Anglia, had Norse and English names respectively, they were presumably of mixed ancestry. Having been Cnut’s adviser and chaplain by 1020, Stigand somehow also became archbishop of Canterbury in 1052 while remaining bishop of Winchester. He was praised by earlier English historians for surviving the Norman Conquest and engineering Kent’s special status. Nevertheless, as a native who had grown rich serving several pre-Norman monarchs, he was doomed. His concurrent tenure of the bishopric and archbishopric had long since antagonised the Vatican, yet William exploited his collaboration to appease the English while power was secured. In 1070, however, papal legates were permitted to intervene. Stripped of his titles and property and incarcerated at Winchester, Stigand died and was buried there. He was propagandistically depicted at Harold II’s ‘illegal’ coronation in the Bayeux Tapestry; and his successor Lanfranc cited his excommunication as a pretext for reimagining the Church on Norman lines.

Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury (~1005-89)

Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury (~1005-89)

Born at Pavia in Lombardy, the capital of Imperial Italy within the Holy Roman Empire, Lanfranc studied law, but then saw a career opportunity in Normandy, where William the Bastard was making a name for himself. After establishing a school, he made the leap to Benedictine prior at Bec Abbey in 1041, and facilitated William’s marriage. Promoted to Abbot of St Stephen’s Abbey in Caen in 1062, he was ideally placed when his boss became William the Conqueror and sought a Norman replacement for Stigand, the Anglian Archbishop of Canterbury. Lanfranc assumed the role in 1070, devoting himself to maintaining the independence of the Anglo-Norman Church, asserting Canterbury’s primacy over York, and replacing Saxon officials with Norman ones. A true power behind the throne, he presented a solid foil to William’s unscrupulous brother Bishop Odo, and secured the succession of William Rufus. Among the Norman invaders, he is probably best considered the least bad of a bad bunch.

Odo, Bishop of Bayeux (d 1097)

Odo, Bishop of Bayeux (d 1097)

If Odo had an epithet, it would be ‘the Odious’. As Bishop of Bayeux and half-brother to William of Normandy, he participated at the Battle of Hastings; and, after the victorious Normans had purloined almost all English land and wealth, Odo took a share second only to the Conqueror’s. He was made Earl of Kent, settling near Harrietsham. It was probably he who ordered the English to celebrate their own downfall by embroidering the Bayeux Tapestry, which ended up at his home cathedral. For a holy man, he took an unhealthy interest in mammon. At the Penenden Heath Trial in 1076, he was successfully arraigned, despite being William’s right-hand man, for stealing Church property. Undaunted, he illegally planned a military expedition to Italy, possibly with the aim of making himself Pope, for which he was gaoled for five years. He later supported a failed rebellion against William II, and mercifully died in Sicily on the 1st Crusade.

Gundulf of Rochester (~1024-1108)

Gundulf of Rochester (~1024-1108)

Gundulf was no wizard, except of architecture; his Tolkien-like Norse name simply reflects the fact that he was born in Normandy. Before the invasion of England, he was a monk at Caen’s St Etienne Abbey. Archbishop Lanfranc of Canterbury brought him to Kent in 1070 to help accelerate the Normanisation of Anglo-Saxon monasteries. Around 1078, King William ordered Gundulf to construct a stone keep to secure London against revolt, the outcome being the White Tower around which the Tower of London evolved. Meanwhile, after Lanfranc secured lands in Rochester previously awarded to William’s half-brother Odo, Gundulf – who himself became Bishop in 1075 – erected the new Cathedral in 1083. He was also responsible for St Bartholomew’s Hospital (1078) and the Castle (ca 1088) in Rochester, and St Leonard’s Tower (1080) and St Mary’s Abbey (ca 1092) in West Malling. It seems a trifle unfair that William of Rochester was canonised for being murdered, while Gundulf of Rochester’s industriousness went unacknowledged.

St Anselm of Canterbury (ca 1033-1109)

St Anselm of Canterbury (ca 1033-1109)

Anselm of Aosta in the far north-west of Italy was Archbishop of Canterbury for the last sixteen years of his life, during which time he was twice exiled for defying the English monarch. He is however better remembered as the Father of Scholasticism. This was a way of thinking critically that came to dominate Europe for half a millennium. Anselm sought to restore the credibility of Roman Catholic doctrine at a time when mysticism was normal. Arguing that faith in God’s existence preceded knowledge, he advocated inferring all facts from faith and depending only on Aristotle for earthly evidence. All contradictions between faith and observable ‘truths’ were to be resolved by arcane disputation among clerics – a practice ridiculed in later centuries as concerning the number of angels that can stand on a pinhead. Though canonised for his ingenuity and dutifully buried in the Cathedral, Anselm is reviled by modernists for having held back the scientific revolution for centuries.

Eadmer (~1060-~1126)

Eadmer (~1060-~1126)

Eadmer was that rarity, an Anglo-Saxon who thrived in the early days of the Norman Conquest. He started adult life at St Augustine’s Abbey in Canterbury. There he encountered the visiting Anselm of Aosta, who was to have such a profound effect on the nature of religious and scientific thought. When Anselm returned as Archbishop in 1093, their friendship became more formal, because the Pope made Eadmer Anselm’s director. He was therefore well placed to write an authoritative biography of the future saint. It was one of several works he penned, the best of which was his ‘Historia Novorum in Anglia’, essentially an account of the first half-century of Norman rule, albeit with an ecclesiastical emphasis. He became particularly associated with the notion of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary, an idea actually repudiated by Anselm yet nevertheless persistent. Eadmer might himself have become Bishop of St Andrews, had Scotland not refused to recognise Canterbury’s hegemony.

Stephen, King of England (1092/6-1154)

Stephen, King of England (1092/6-1154)

Stephen of Blois was a grandson of William the Conqueror. Already wealthy, he made a profitable marriage that brought in valuable estates in Kent and Boulogne. He had sworn to support his cousin Matilda’s claim to the throne, she being the daughter of King Henry I and soon to be widow of the Holy Roman Emperor. After she married Geoffrey of Anjou, however, the Anglo-Normans and the English Church turned against her, and Stephen usurped the throne on Henry’s death in 1135. He then spent his entire reign fighting off rebellions, not least an invasion by the Empress Matilda that became the centre-piece of the 18-year Anarchy. His desperate plans to secure the succession for his son Eustace failed when the prince died in 1153. Resigned to ceding the throne to the Angevins, he set about patching up the damage, but soon died at Dover, and was buried with his wife and son at Faversham Abbey.

St Thomas Becket (1120-70)

St Thomas Becket (1120-70)

Becket is revered today for being murdered in the Cathedral by four of King Henry II’s knights. Ironically, until his grisly end, he was deeply unpopular. Though born in Cheapside, Becket was altogether Norman, a scion of the invader overclass that still lorded it over their Saxon vassals. He’d originally been Lord Chancellor, but was appointed by his friend the King to the position of Archbishop of Canterbury so that they could reassert royal authority over the Church. Once in position, however, the cussed Becket refused to play ball. Even after being allowed home from exile, he continued to be a bane, and even excommunicated three bishops for carrying out the King’s wishes. The bloody denouement was the stuff of gangster movies, when four goons wasted the rival gang leader after being sent only to rough him up. At least St Thomas the Martyr has had the last laugh in folk mythology.

Baldwin of Forde, Archbishop of Canterbury (~1125-90)

Baldwin of Forde, Archbishop of Canterbury (~1125-90)

Baldwin, a Devonian, was sent to Italy in his twenties, and worked as tutor to Pope Eugene III’s nephew. A specialist in canon law, he became a monk around 1170, and was appointed Abbot of Forde Abbey in Dorset before becoming Bishop of Worcester in 1180. Given Baldwin’s obvious talent, Henry II practically insisted on his selection as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1184. Nevertheless, he got embroiled in a bitter dispute with Christ Church Priory that remained unresolved. In 1189, he crowned Henry’s son Richard I, who despatched him to Tyre on the 3rd Crusade with a vanguard of about 500 men. They arrived in time to assist the escape of the Frankish besiegers of Acre, who were surrounded by Saladin’s army. Though Baldwin participated in the fighting, he was already sick. While preparing to excommunicate Crusader allies with whom he had fallen into dispute concerning the succession to the Kingdom of Jerusalem, he died even before Richard’s arrival.

Hubert de Burgh, Earl of Kent (~1170-1243)

Hubert de Burgh, Earl of Kent (~1170-1243)

De Burgh rose from obscure origins in Norfolk to become a major support to King John as an ambassador, in battle against Philip II of France, and in the 1st Barons’ War, including the ratification of Magna Carta. His dedication enabled him to buy the manor of Tunstall, and earned him such posts as Sheriff of Kent and Constable of Dover. When John died in 1216, his successor Henry III was only nine, so de Burgh assumed the role of regent. In 1217, he commanded at the Siege of Dover Castle and the 2nd Battle of Sandwich, emerging triumphant. He became the castellan of Rochester Castle, Earl of Kent, and Chief Justiciar, a Norman post affording unique powers outside the royal household, and married Margaret, sister of Alexander II of Scotland. Naturally his political weight incurred the animosity of rivals, and in 1232 he was imprisoned and stripped of his estates. Shakespeare later wrote him into ‘King John’.

Walter de Merton (~1205-77)

Walter de Merton (~1205-77)

Walter, from Hampshire, went into holy orders, but built a career as much in politics as religion. He was a skilled negotiator, out of whom Henry III got good use at a time of serious upheaval on account of the baronial revolt. Such was his loyalty that he became Lord Chancellor in 1261, and stood in for Edward I for two years while he was away on the 9th Crusade. He acquired his surname from a house he set up in Surrey to accommodate scholars of Merton Priory. After ten years, that institution moved to Oxford and, thanks to the pains he took to set it on a level footing, became today’s Merton College, with its vaunted Field and Recreation Ground. Relieved of the Lord Chancellorship, he was compensated by Edward by being made bishop of Rochester. Dividing his time between Merton and Rochester, he fell from his horse when fording the Medway, with fatal consequences.

Henry III, King of England (1207-72)

Henry III, King of England (1207-72)

Although one of the less familiar Norman kings, Henry III remained England’s longest-reigning monarch until George III five centuries later. Born at Winchester, he was just nine when his father King John died. At 20, he threw off his advisors’ constraints and embarked on a warlike policy towards France, but his military efforts proved a fiasco. After his staunch supporter Hubert de Burgh fell from grace in 1232, the corruption of Henry’s Savoyard in-laws increasingly excited the hostility of the baronial caste, until in 1263 Simon de Montfort initiated the 2nd Barons’ War. Henry was actually captured at Lewes in 1264, but his talented son Prince Edward escaped and, at the Battle of Evesham a year later, saw de Montfort put to death; the King meanwhile had to be rescued by Roger de Leybourne. By nature an easy-going type, Henry and his wife, Eleanor of Provence, instituted the royal practice of spending Christmas at Eltham Palace.

Simon de Montfort (1208-65)

Simon de Montfort (1208-65)

De Montfort came to England from the Paris area at the age of 21, hoping to succeed to the Earldom of Leicester. Though speaking no English, he was welcomed by Henry III, whose court was French-speaking. In 1238 he married Eleanor of England, Henry’s sister and the Earl of Pembroke’s widow, who had inherited Sutton Valence Castle from her first husband. Repeated disputes with the feeble king eventually turned to civil war in 1263, when the populist but anti-Semitic de Montfort led a baronial revolt seeking parliamentary reform and a Jewish pogrom. After a temporary reverse, he spectacularly won the Battle of Lewes (1264), capturing Henry and his son Edward. He then innovated his ‘Great Parliament’, the first to embrace the citizenry. Unluckily for him, the charismatic young Prince Edward escaped and led a superior force of disaffected barons against him at Evesham. De Montfort and his men were cut to ribbons, and democracy would have to wait.

Eleanor of Provence (~1223-91)

Eleanor of Provence (~1223-91)

Henry III picked an unusual venue for his first date with the Count of Provence’s daughter in 1236: the altar of Canterbury Cathedral. She was 12, he was 28; but uxorial suitability generally ranked a distant second to dynastic politics back then. Norman England’s usually foreign queens seldom courted popularity, but Eleanor was exceptionally contemptuous. She arrived in England with no dowry, but flooded the royal court with her kin, known as the Savoyards. A dedicated follower of fashion, she funded her lifestyle by extorting ‘queen-gold’ and other spurious imposts from London’s populace. The mutual loathing got so bad that, when she went barging on the Thames in 1263, Londoners pelted her with rotten vegetables, mud, and even rocks; she had to be rescued. She perhaps imagined she might earn popularity by expelling all Jews from her estates in 1275. She was buried in Wiltshire in an unmarked grave. Her one good legacy was her eldest son, Edward I.

Edward I, King of England (1239-1307)

Edward I, King of England (1239-1307)

Edward Longshanks, the young prince who turned the tables on the Baron’s Revolt, was to prove a match for more than just Simon de Montfort. The clue is in his epithet, ‘Hammer of the Scots’, earned by his savage treatment of the Auld Enemy after he’d already wreaked havoc in Wales and gone crusading. This made him wildly popular in England, though he was more feared than liked by those about him. His imposing physique and violent temper did at least aid him in restoring order among the barons after the turmoil of his inept father’s reign. His legislative amendments brought temporary stability, although he enshrined anti-Semitism in English law for centuries. He chose to live with his first wife Eleanor of Castile at Leeds Castle, where she bore many of their sixteen or so children. Sadly, his successor would be his son Edward II, the disastrous monarch who would quickly undo all his work.

Eleanor of Castile, Queen of England (1241-90)

Eleanor of Castile, Queen of England (1241-90)

Like most royal matches, King Edward I’s with Eleanor was political, intended to reinforce English control of Gascony. Nevertheless, it was a strong one. The two would remain devoted for life, even if the story of Eleanor saving the King’s life on the Ninth Crusade by sucking poison from an assassin’s wound is far-fetched. Their compatibility may have owed something to a common temperament, her feistiness being a foil for his own. Yet she by no means shared in his popularity. Barely able to speak English, she spent her time at their home at Leeds Castle trading in properties with recklessly borrowed money. Most of the numerous children she bore died young, and her only son who grew to adulthood was her very last child, the hopeless Edward II. Even so, after she died near Lincoln, the distraught King had memorial crosses erected at each stop on the long walk home with her body, the last of them being at Charing, Middlesex.

Edward II, King of England (1284-1327)

Edward II, King of England (1284-1327)

If it hadn’t been for the early death of Isobel of Castile’s eldest surviving son, England would have had a King Alphonso. Instead, in 1307, it got Edward II, who at 21 had been gifted Eltham Manor by the Bishop of Durham, and spent Christmas at Wye Court while awaiting his coronation. His 20-year reign was economically described in the title of Marlowe‘s bioplay as “troublesome”. It might be argued charitably that Edward was unlucky to be sandwiched between his father Edward I and son Edward III, both of whom were outstanding leaders and national heroes. Contrariwise, he scandalised the Baronial caste with his relationship with Piers Gaveston, whom they eventually executed. Edward’s mismanagement led directly to the calamitous defeat at Bannockburn in 1314, and his relationship with the rapacious Hugh Despenser the Younger even caused his wife, Isabella of France, to rebel against him. He was eventually murdered at Berkeley Castle, legendarily with a painfully inserted red-hot poker.

Elizabeth de Brus, Queen of Scotland (~1289-1327)

Elizabeth de Brus, Queen of Scotland (~1289-1327)

Elizabeth de Burgh was a product of the era when Anglo-Scottish relations were largely a civil war between Britain’s Norman overlords north and south of the border. Her father was Richard Og de Burgh, an Ulster-based friend of England’s Edward I. She met Robert de Brus, the Scottish Earl of Carrick, at Edward’s court, and they married in Essex in 1302. After they boldly crowned themselves King and Queen of Scotland in 1306, however, she was taken prisoner and held captive in a succession of castles, ending with Rochester. Luckily for her, ‘Robert the Bruce’ had legendarily learned perseverance from a spider, while Edward had been succeeded by his worthless son Edward II. After Bruce triumphed at Bannockburn in 1314, Elizabeth was allowed home in a prisoner exchange. Although she died prematurely after falling off her horse, she had co-reigned for 13 years over an independent Scotland whose future James VI would one day rule England.

Philippa of Hainault (1310?-69)

Philippa of Hainault (1310?-69)

Unlike several foreign-born queens of England who earned public disapproval, Philippe de Hainaut (sic) appears to have enjoyed a genuinely collaborative relationship with her husband, Edward III, which endured through 40 years of the Hundred Years’ War. As her name suggests, she was born in the Low Countries, the Count of Hainaut’s daughter. She and Edward, her second cousin, were married in 1328 in consequence of his father Edward II’s eagerness to forge a political alliance in the region. The tenant of Leeds Castle, she appointed Jean Froissart as her secretary, and in addition to bearing 13 children, including Edward the Black Prince, was instrumental in getting Flemish weavers established in England. She stood in as regent in 1346 while Edward was fighting in France, and famously persuaded him to show mercy after the Siege of Calais in 1347. Queen’s College, Oxford was named after her. Strangely, she came fifth in the ‘100 Great Black Britons’ poll in 2003.

Thomas Beauchamp, 11th Earl of Warwick (1313-69)

Thomas Beauchamp, 11th Earl of Warwick (1313-69)

In 1319, the Earl of March, regent during Edward III’s minority, married his infant daughter Katherine to Thomas Beauchamp. This wealthy young Lord Warwick cut his teeth with years of military service in Scotland, and so proved himself as both soldier and commander that he became Marshal of England, supervised the young Black Prince in battle, and was appointed the third Knight of the Garter. A major force in Edward’s French campaigns, he played a senior role at the triumphs of Crécy (1346) and Poitiers (1356). Being required repeatedly to sail from Sandwich and Dover, he would base himself at the manors of Rainham and Easole (Nonington) he had inherited from his younger brother Sir John. Such was his reputation that, at his approach in 1369, Philip the Bold of Burgundy fled Calais in the night. After raiding Normandy with John of Gaunt, Beauchamp died at Calais of plague, as his brother had nine years earlier.

Edward III, King of England (1312-77)

Edward III, King of England (1312-77)

When he was 13, Prince Edward’s mother Queen Isabella deposed his father Edward II and installed herself and her lover as regents. Fortunately, the boy was made of sterner stuff than his clueless father. He assumed the kingship at 17 after banishing her and executing the lover, and embarked on military campaigns to subdue the Scots and to claim the French throne. He enjoyed tremendous successes, his son the Black Prince securing historic victories at Crécy and Poitiers. Edward’s misfortune was that, having acceded so young, he ruled for half a century. Despite enjoying leisure time with his agreeable wife Philippa of Hainault at their country retreat, Leeds Castle, exhaustion took its toll. He later suffered such reverses, both domestically and in foreign affairs, that his ambitions ultimately went unfulfilled. Then the Black Prince predeceased him, and the succession passed to his unstable grandson Richard II. In no time, England was again in turmoil.

Wat Tyler (d 1381)

Wat Tyler (d 1381)

Walter Tyler won notoriety as the leader of the Peasant’s Revolt, the direct cause of which was a new fourpenny poll tax. Tyler, who was probably from Kent or Essex, led a pitchfork army from Canterbury to London to demand rights for the peasantry. After crossing London Bridge, his men wreaked havoc, and the young King Richard II felt bound to meet Tyler and offer concessions. In this winning position, however, Tyler’s hubris let him down. At a second meeting at Smithfield, he provoked one of the King’s men into insulting him, whereupon he attacked first the noble and then the Lord Mayor, who cut him down with his sword. His head was displayed on the end of a pole as a warning. And so the Revolt, which had come close to success, failed for want of a modicum of restraint. Tyler nevertheless became a folk hero, and has a road named after him in Kent’s county town.

Edward, the Black Prince (1330-76)

Edward, the Black Prince (1330-76)

To England, Edward of Woodstock was the heroic Prince of Wales who twice made a mockery of overwhelming French superiority: at Crécy in 1346, and Poitiers ten years later. To France, however, he was a brigand who unchivalrously despoiled and looted the French interior, and mercilessly massacred hordes of prisoners. The king of France, John the Good, didn’t seem bothered; he accepted Edward’s invitation to dinner at Dover on his way home from exile in 1360, Edward having a home at Northbourne. Nicknamed the Black Prince after the colour of his armour, rather than his reputation for ruthlessness, Edward would have made a good successor to Edward III in the hard-man mould of Edward I; but he was enfeebled by dysentery, and felled by it at 45. Unluckily for England, his son Edward had also died young, so the throne passed to the boy’s awful brother, Richard II. The Black Prince now lies serenely in Canterbury Cathedral.

John Ball (~1338-81)

John Ball (~1338-81)

John Ball, a priest originally from Colchester, was evidence of the idea that socialism is a restatement of radical Christian values for a secular age. Having lived through the Black Death, he grew appalled by its consequences, notably the inequality of wealth that persisted among the overworked survivors. For his unorthodox utterances, this ‘Mad Priest of Kent’ was jailed in Maidstone. He was released by insurgents during the Peasants’ Revolt, whereupon he proceeded to the rebel army’s rallying point at Blackheath. There he made a stirring speech beginning, “When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?” and exhorting workmen to “cast off the yoke of bondage” in a distinctly Marxist tone. When the revolt failed, Ball was imprisoned, tried, and sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered. Even King Richard II himself turned up in St Albans to enjoy the spectacle, and got into the redistributive spirit by sharing Ball’s body-parts around.

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (1340-99)

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (1340-99)

The founder of the House of Lancaster, John of Gaunt is unique in being an ancestor of all subsequent British monarchs. He was born at Ghent in the Low Countries, and got his Anglicised surname from Shakespeare. He was the younger brother of Edward the Black Prince, whose young son Richard II he controlled after Edward III’s death in 1377; he started by appointing himself constable of the important new castle at Queenborough. Nothing like the warrior his brother had been, he enriched himself through political machinations and lucrative marriages. His second, to Constance of Castile, even led him to claim Castile’s throne, but his expedition to claim it in 1387 was an unmitigated failure. Nevertheless, his son Henry of Bolingbroke by his first wife Blanche of Lancaster deposed Richard immediately after John’s death and became Henry IV. Furthermore, John’s mistress Katherine Swynford, whom he married in 1396, bore a son whose great-grandson was Henry Tudor.

Geoffrey Chaucer (1340s-1400)

Geoffrey Chaucer (1340s-1400)

The consequence of writing ‘The Canterbury Tales’, the most famous of all medieval works in English, is that Chaucer is generally known for little else, despite his extraordinarily rich life. The son of a London vintner, he was captured as a teenager during an invasion of France and ransomed by King Edward III. Marrying one of the Queen’s attendants brought a family connection with his future patron, John of Gaunt. From 1367 he remained in the King’s service, initially as a diplomat; his visits to Italy crucially introduced him to Petrarch and Boccaccio. He started writing poetry seriously around 1370, commencing his magnum opus in 1387. By then he had moved to Greenwich and become MP for Kent; he was additionally a senior bureaucrat in customs and public works. Remarkably, in his spare time he even wrote a ‘Treatise on the Astrolabe’. He was the first to be buried at Westminster Abbey’s Poets Corner.

Henry Chichele, Archbishop of Canterbury (~1364-1443)

Henry Chichele, Archbishop of Canterbury (~1364-1443)

A native of Northamptonshire, Chichele went to Oxford and acquired a training in ecclesiastical law that soon brought him rewards. It also equipped him for diplomacy. He was born at the time of the Papal Schism, when two popes reigned simultaneously in Pisa and Avignon. He repeatedly undertook missions to Italy to negotiate a reunification, but when he met with failure participated in 1409 in a project to install a new pope in place of both. He also undertook successful missions to France of a secular nature. Chichele became Archbishop of Canterbury for life in 1414, and embarked on vigorously persecuting heretics. In 1438, he founded Oxford’s College of the Souls of All the Faithful Departed, or All Souls, to commemorate the dead of the Hundred Years’ War. He was buried at the Cathedral, his macabre tomb displaying a life-size effigy of him peacefully at prayer above another of his rotting corpse.

Anne of Bohemia, Queen of England (1366-94)

Anne of Bohemia, Queen of England (1366-94)

When he had been on the throne for five years, the young Richard II was supposed to marry the daughter of the Lord of Milan, which would have brought a large dowry. Instead, in 1382, he was wed to his fellow 15-year-old Anne of Bohemia. She was the daughter of Charles IV, the Holy Roman Emperor who ruled about half of Europe, and sister to his successor Sigismond. This political alliance was considered an important means of counterbalancing French support for the Antipope Clement VII during the Papal Schism, and Richard paid over £4 million in today’s money to secure it. Anne was immediately gifted Leeds Castle, having spent Christmas there before their January wedding. Well thought of as a benefactor of the arts and a support to supplicants, she may also have reined in Richard’s wilder impulses. After she died childless, probably of plague, while residing at Sheen Palace, Richard’s behaviour became increasingly unrestrained, and eventually dangerously so.

Richard II, King of England (1367-1400)

Richard II, King of England (1367-1400)

Thanks mainly to Shakespeare’s ‘Richard II’, posterity has a low opinion of the son of Edward the Black Prince and Joan of Kent. Richard succeeded his grandfather Edward III aged ten, his father having died of dysentery. He boded well at first, sharing his wife Anne of Bohemia’s passion for patronising the arts rather than going to war. He held court at Leeds Castle, where he welcomed the likes of Froissart. However, these were martial times, and a clique of ‘Lords Appellant’ took exception to him. Although a reconciliation was effected, Richard grew increasingly vindictive. He made a thoroughgoing enemy of Henry Bolingbroke, who in 1399 forced him to abdicate and took the throne as Henry IV. Richard was imprisoned in Leeds Castle and elsewhere, and is believed to have been starved to death. Shakespeare painted him as the author of his own undoing; his problem may have been a personality disorder.

Henry IV, King of England (1367-1413)

Henry IV, King of England (1367-1413)

As the eldest son of the ambitious John of Gaunt, Henry of Bolingbroke in Lincolnshire probably felt obliged to press his debatable claim to the throne; but he could have been forgiven for wishing he hadn’t. He married 11-year-old heiress Mary de Bohun at 13, which brought him wealth and, eventually, six children. Although he initially supported his cousin Richard II, the King denied him his father’s estates, so Henry usurped the throne in 1399, initiating Lancastrian rule that would sow discord until after 1485. Already during his reign, Henry faced two major threats, from Owen Glendower in Wales and ‘Harry Hotspur’ Percy in Shropshire. With the help of his son Prince Harry, he put down both, but they took a toll. Despite relaxing with his second wife Joan of Navarre at his favoured Eltham Palace for ten of the thirteen Christmases of his rule, he died of chronic illness, and was buried at Canterbury Cathedral.

Joan of Navarre (~1368-1437)

Joan of Navarre (~1368-1437)

Joan, the daughter of the King of Navarre in the Basque region, was married to Duke John IV of Brittany for 13 years until he died. She and Henry IV grew attached during his exile in Brittany, and she married him in 1403. So it was that she became the second in a succession of highly unpopular foreign Queens of England. One reason was that, though regal, she was unduly rapacious. The other was her dislike of the English, which led her to favour the company of her Breton courtiers to such an extent that Parliament eventually exiled them. After Henry‘s death in 1413, she got on well with her stepson Henry V at first, but ill feeling developed until he took her property and imprisoned her successively at Pevensey Castle and Leeds Castle. She was released just before his death, residing thereafter at Nottingham Castle. She was buried alongside Henry IV in the Trinity Chapel of Canterbury Cathedral.

Isabella of Valois (1389-1409)

Isabella of Valois (1389-1409)

That Isabeau de Valois was only six when Richard II of England needed a new wife was no obstacle to a fine political match. The daughter of King Charles VI of France, she was deemed a good prospect for the future by 29-year-old Richard after the death of his first wife Anne of Bohemia, even if consummation would have to be delayed until she passed twelve. The marriage reportedly worked: she was pleased to become such an important personage, and he entertained her at Eltham Palace like a kid sister. She was still only nine when he was toppled, and ten when he died. Henry IV wanted her to marry his son Henry of Monmouth, the future Henry V. She refused, and instead married her cousin, the future Duke of Orléans, in 1406, while Henry V married her sister, Catherine of Valois. After so much trouble, Isabella died in childbirth at 19, although her daughter Jeanne did survive.

Charles, Duke of Orléans (1394-1465)

Charles, Duke of Orléans (1394-1465)

After the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, Richard Waller (ca 1395-1461) of Groombridge Place discovered the Duke of Orléans still alive under a pile of corpses, and took him prisoner. As the French king’s nephew, Charles was so dangerous politically that Henry V forbade a ransom. He spent much of his 25-year captivity as the guest of Waller, who was knighted. Despite his homesickness, he proved an admirable prisoner. Having gained a huge dowry by marrying Richard II’s short-lived widow Isabella of Valois, he contributed lavishly to public works, including the construction of Speldhurst church, which bore his coat of arms until it burnt down in 1791. Above all, he was a prolific poet. Though he wrote highly complex poetry, he is best known for composing the first Valentine poem, sent to his second wife back home. He was eventually ransomed in 1440 and enjoyed a quarter century with his third wife back in France as a literary celebrity.

Catherine de Valois, Queen of England (1401-37)

Catherine de Valois, Queen of England (1401-37)

When Catherine entered history in 1420, she was an 18-year-old ingénue who happened to be the daughter of King Charles VI of France. Her appeal to King Henry V of England was not just sexual: by marrying her, he became heir to the French throne. Their marriage lasted only two years before he died of dysentery, bequeathing Leeds Castle to her. By then she’d borne him an heir; it was not her fault that he was Henry VI, whose utter incompetence sparked the Wars of the Roses. Less blamelessly, she then defied a Parliamentary decree to get embroiled with an ambitious Welsh courtier called Owain ap Tudur. Their bastard son would father the Harri Tudur who abused his royal connection to usurp the English throne in 1485. Given her talent for unwitting trouble-making, she is appropriately best known for the scene in Shakespeare’s ‘Henry V’ when she gets to speak the foulest of words; pure ‘Carry On’, but funnier.

Margaret of Anjou, Queen of England (1430-82)

Margaret of Anjou, Queen of England (1430-82)

Amid a succession of unloved foreign Queens of England, Marguerite d’Anjou takes the biscuit. She was the daughter of René, King of Naples, a man described as “all crowns and no kingdoms”. Landing his 15-year-old daughter’s marriage to the King of England must have struck him as an absolute godsend. Even better was the fact that her new husband, Henry VI, was an idiot, so she was free to rule the roost. Having seized Placentia Palace in Greenwich, she pursued the same preoccupations as Nero’s mother, Agrippina: her own wellbeing, and her son’s succession. All else was expendable, not least public safety. It was her crass imperiousness that prompted the Yorkist revolt, and her bloody-mindedness that sustained the conflict beyond endurance. She was hated with a passion, and none shed a tear when, in 1471, she was defeated at Tewkesbury and her young son killed. Shattered, she fled to France, and lived her last decade as a pauper.

Edward IV, King of England (1442-83)

Edward IV, King of England (1442-83)

Among the dubious protagonists of the Wars of the Roses, Edward IV was arguably the most charismatic. Having succeeded his father Richard, Duke of York, who was killed at Wakefield in 1460, he deposed the Lancastrian king Henry VI by defeating him at Towton in 1461. He then secretly married Elizabeth Woodville for largely sexual reasons, which so outraged his ally the Duke of Warwick that Edward too was deposed and banished in 1471. Undaunted, he sought the help of the Burgundians, invaded from France, and crushed the Lancastrian army at Barnet. Warwick was killed, heralding twelve years of stable Yorkist rule. Edward was, however, an incorrigible man of the flesh. One Christmas, he threw a banquet for 2,000 in the great hall he had built at Eltham Palace. Only months later, he fell ill, and died of unknown causes. His brother Richard usurped the throne, bringing dire consequences for some of Elizabeth’s closest kin.

The Duke of Clarence (1449-78)

The Duke of Clarence (1449-78)

George Plantagenet was one of those rare individuals better known for his manner of death than anything he did. He grew up in Greenwich, the son of Richard of York and brother of two future Kings of England, Edward IV and Richard III. When Edward took the throne in 1461, George became the 1st Duke of Clarence. Had he been patient, he might himself have succeeded, being older than Richard; but he was inclined to mental instability and questionable decision-taking. When his father-in-law, the Earl of Warwick, turned against the Yorkists in 1469, the foolhardy Clarence backed him in the belief that he would be installed as king in his brother’s place. Disappointed, he returned to the Yorkist cause, but repaid his brother’s forgiveness by again rebelling in 1477. This time, King Edward had him tried for treason and executed. According to tradition, he was imaginatively drowned in a butt of Malmsey wine.

William Warham, Archbishop of Canterbury (~1450-1532)

William Warham, Archbishop of Canterbury (~1450-1532)

Having been born a farmer’s son in Hampshire, Warham went to Oxford, took holy orders, and practised law. By 1494, he was Master of the Rolls. He served Henry VII well as a diplomat, helping arrange Prince Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon, and conducting negotiations with the Scots and with the Holy Roman Emperor. He became the Bishop of London in 1501, but in no time progressed to Lord Chancellor and Archbishop of Canterbury, and then Chancellor of Oxford University. He showed evidence of his political instincts in 1515 by resigning as Lord Chancellor in favour of the ill-fated Cardinal Wolsey, presumably suspecting what was ahead. Having accompanied Henry VIII to the Field of the Cloth of Gold, he took the stance that the King’s anger meant death, and so acquiesced as far as his conscience allowed. He died just in time to avoid Henry’s lethal marital upheavals, and has a prominent tomb in Canterbury Cathedral.

Richard III, King of England (1452-85)

Richard III, King of England (1452-85)

Arch-villain, as per Shakespeare, or just an unlucky pragmatist? It is hard to be sure about Richard. He was raised with elder brother George in a tower at Placentia Palace in Greenwich after their father Richard of York fled the country. He stuck loyally with his eldest brother, Edward IV, throughout the bitter civil war. Come Edward’s death in 1483, however, he took on another hue. He used a legal ruse to argue that Edward’s young sons Edward and Richard were conceived illegitimately, and seized the crown for himself; the two ‘Princes in the Tower’ were never seen again. He might have argued that it was necessary for England’s sake, given the imminent threat from the Tudors. All was lost in any case at Bosworth in 1485, when the usurper Henry VII ended Richard’s life, the Plantagenet dynasty, the Wars of the Roses, and the Middle Ages. Richard’s skeleton was eventually found in 2012, and respectfully reburied at Leicester Cathedral.

St John Fisher (1469-1535)

St John Fisher (1469-1535)

The epitome of the dour Yorkshireman, John Fisher studied at Cambridge before becoming Margaret Beaufort’s chaplain. A year after his appointment as a Divinity professor in 1503, he was made chancellor of Cambridge University and Bishop of Rochester, where he remained for the rest of his life. He was known for his extreme spiritual uprightness, and liked to remind others of their mortality by placing a skull on the altar at prayer time, and on the dining-table at supper time. Author of an outspoken critique of Luther in 1523, he unsurprisingly had no truck with the determination of the supposed ‘Defender of the Faith’, Henry VIII, to implement an English Reformation for dynastic and libidinous reasons. By insisting on papal supremacy in Church matters, he effectively signed his own death warrant. He was beheaded on Tower Hill, a fortnight before Sir Thomas More went the same way. Exactly four centuries later, he was canonised as a martyr by Pope Pius XI.

Cardinal Wolsey (1473-1530)

Cardinal Wolsey (1473-1530)

Thomas Wolsey’s life encapsulated the principle that supping with the devil demands a long spoon. From humble origins in Suffolk, he became a priest after studying Theology at Oxford. He was appointed chaplain to the Archbishop of Canterbury and rector of Lydd, although it is debatable whether he preached there. He was royal chaplain under Henry VII, and his rise to fame and riches grew meteoric under Henry VIII. He became Archbishop of York in 1514 and then a cardinal; yet his secular power was no less impressive, culminating in the Lord Chancellorship. It all went pear-shaped when Henry took a fancy to Anne Boleyn. Wolsey was charged with securing Henry’s divorce from Queen Catherine. Seeing the likely consequences, he actively resisted. Henry responded by relieving him of his government titles and Hampton Court Palace, and then summoning him to be tried for treason. Wolsey saved himself a lot of pain by expediently dying en route.

Sir Thomas More (1478-1535)

Sir Thomas More (1478-1535)

It’s unsurprising that Erasmus’s best friend in England was Thomas More. Both were learned, humanistic, and Catholic; but More went further. Born into a wealthy London family, he served as a household page to the Archbishop of Canterbury, who lived at Knole House. After Oxford, he studied law. He actually accompanied Erasmus on that famous visit to Eltham Palace, and later would get to know Prince Henry all too well. An MP at 26, he was knighted in 1521 for services to the King, succeeding Wolsey as Lord Chancellor eight years later. It was an untimely appointment, with Henry’s divorce from Catherine on the cards. Sir Thomas was a devout Catholic, who wore a hair-shirt and might have become a monk. Out of principle and obstinacy, he refused to endorse the King’s ‘great matter’, literally to the death. The martyr was canonised by Pope Pius XI in 1935, ironically after his satire ‘Utopia’ had made him a Bolshevik hero.

Catherine of Aragon, Queen of England (1485-1536)

Catherine of Aragon, Queen of England (1485-1536)

Catalina de Aragon was one of the more pitiable figures in history. Her illustrious parents were Ferdinand and Isabella, who’d completed the reconqista of Spain and unified the Spanish nation. At 15, she married Prince Arthur, heir to the English throne, who died after just five months. Seven years later, she wed his brother, King Henry VIII. Living at Leeds Castle, she acquitted herself well, even serving as regent in Henry’s absence. Her one failure lay in the matter of providing a male heir. The nearest she came in six pregnancies was a would-be Henry IX who died after seven weeks; only the future Mary I survived. In 1533 her impatient husband had the marriage annulled, took up with Anne Boleyn, and ejected Catherine from court. She was shunned, moved from place to place, and took to wearing a hair shirt; and still she refused to recognise the divorce. When she died, daughter Mary was even forbidden to attend the funeral.

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556)

Archbishop Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556)

It fell to Nottinghamshire-born academic Thomas Cranmer to pick up the pieces of King Henry VIII’s repudiation of the Roman Catholic Church. Cardinal Wolsey turned to him at Cambridge for support on the matter of Henry’s divorce. It led Cranmer to tour Europe in search of academic advice, during which his encounters with Protestant activists influenced his theological thinking. In 1532, he was surprisingly summoned to the Canterbury archbishopric. As a theological Mr Fixit by royal appointment, he smoothed the passage of Henry’s matrimonial convulsions, whilst under Edward VI he created the Anglican liturgy, including the Book of Common Prayer. Such achievements came back to bite him, however, for he inevitably fell foul of the Catholic Queen Mary. Tried for treason and heresy, he recanted his beliefs, but to no avail; Mary wanted an example made of him. At the last moment, he dramatically renounced his recantation, cursed the Pope, and died a Protestant martyr’s fiery death at Oxford.

John Bale (1495-1563)

John Bale (1495-1563)

A Carmelite friar from the age of 12, John Bale from Suffolk converted to Protestantism in 1533, and thereafter castigated the monastic way of life through miracle plays and mysteries. So coarse was his vitriol that he became known as Bilious Bale, and acquired many enemies; but he was protected by Thomas Cromwell, who reaped the benefits. When Cromwell fell, Bale fled. Recalled under Edward VI, he was made a bishop in Ireland, where his propaganda so antagonised Catholics that they attacked his house and killed five servants. Finally, with Elizabeth I on the throne, Bale was made a prebendary at Canterbury, where he died. Among his less polemical works, the most significant is his ‘A Summary of the Famous Writers of Britain’ (1548), which implausibly starts with Adam. He did make a landmark literary contribution with his first drama, ‘Kynge Johan’ (ca 1538), which represents the dramatic crossover from morality play to historical drama that later became standard.

Mary Tudor, Queen of France (1496-1533)

Mary Tudor, Queen of France (1496-1533)

Born at Sheen Palace, the pet sister of Henry VIII, Princess Mary was regarded officially as a political pawn. She was married off at 18 to Louis XII of France, who was desperate for a son before he died but expired within three months. She turned immediately to her true love, Charles Brandon, the Duke of Suffolk, and married him secretly in Paris against Henry’s expressed wishes. This was treason; but Cardinal Wolsey intervened, and the couple merely had a punitive £24,000 fine imposed on them. They were also made to marry again in Henry’s presence at Greenwich Palace, two months after the original ceremony. The fine was later reduced, and in 1530 they were even gifted Sayes Court. Mary – who incidentally detested Anne Boleyn – bore four children, but was frequently sick, and died at 37 from one of several possible maladies. She was the subject of a play written by Borden dramatist Primogene Duvard in 1844.

Mary Boleyn (~1499-1543)

Mary Boleyn (~1499-1543)

Like her younger sister Anne, Mary Boleyn was probably born at Blickling Hall in Norfolk, but grew up at Hever Castle. Also like Anne, but even earlier, she was Henry VIII’s mistress, and probably bore him two unacknowledged bastards. Unlike Anne, however, who was less attractive but cannier, she failed to secure a royal marriage. Instead she wed William Carey, one of Henry‘s pet courtiers. Their three children included a son, Henry, who grew up to be the Baron Hunsdon who patronised the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, for whom Shakespeare wrote and performed. When Carey died of the ‘sweating-sickness’ in 1528, the King gave Anne custody of her young nephew, Mary having been left penniless. Six years later, Mary remarried secretly, this time with a humble soldier called William Stafford. Since she was one of the Queen’s companions at court, Anne was outraged, and barred her sister from the royal presence. Mary died in no doubt grateful obscurity.

Reginald Pole, Archbishop of Canterbury (1500-58)

Reginald Pole, Archbishop of Canterbury (1500-58)

Perhaps surprisingly, there was one last Catholic archbishop of Canterbury after the English Reformation. Edward IV’s great-nephew Reginald Pole was born in Worcestershire, studied at Oxford and Padua, and became dean of Exeter in 1527. Henry VIII sought his support on his divorce from Catherine of Aragon, but he felt unable to oblige, and left the country in 1532. When pressed by Thomas Cromwell in 1536, he aggressively repudiated and conspired against Henry, who retaliated by beheading most of Pole’s family. Elevated in Rome to cardinal, he might have become pope, but was brought home when Mary I succeeded Edward VI and required help with persecuting Protestants. She made him Archbishop of Canterbury in 1556, after which the martyrdoms proliferated. Nevertheless, Pole sought to rehabilitate the Church of England with Rome, which prompted Pope Paul IV to refer him to the Inquisition. Though safe under Mary’s protection, he saved himself trouble by dying within hours of her decease.

Bishop Nicholas Ridley (~1500-55)

Bishop Nicholas Ridley (~1500-55)

The execution of the ‘Oxford Martyrs’ Nicholas Ridley, Thomas Cranmer, and Hugh Latimer was the nadir of Mary I‘s bloody reign. Ridley, from Northumberland, studied at Cambridge and Paris before progressing up the ecclesiastical ladder, from chaplain at Canterbury (1537) to vicar of Herne (1538) to Bishop of Rochester (1547) and finally Bishop of London (1550). Having renounced transubstantiation, he collaborated with Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury, on the Forty-two Articles expressing the precepts of the new Church of England. A loyal support to Edward VI, he spoke publicly against the legitimacy of both Mary and her sister Elizabeth, and supported the claim of Lady Jane Grey. When Edward died at 15, Mary’s supporters usurped the throne for her, with fatal consequences for Ridley. The new Catholic queen ignored his pointless apology and had him show-tried for heresy. His death at the stake was notoriously horrific, but in Latimer’s words lit a candle that would never be put out.

Anne Boleyn, Queen of England (~1501-36)

Anne Boleyn, Queen of England (~1501-36)

Nan Bullen was probably born at her family’s second home in Norfolk, but is most associated with Hever Castle. After two proposed marriages had fallen through, in 1526 she drew the attention of the priapic King Henry VIII, who already enjoyed her elder sister Mary as a mistress. Anne refused to sleep with him unless as his Queen. His ardour for her became the primary driver of his campaign to divorce his wife, even though it meant forcing a historic rupture with the Roman Catholic Church. Not until 1533 could they marry, just three months before Anne gave birth to the future Queen Elizabeth I. There followed three miscarriages in three years, however, prompting the King to transfer his interest to Jane Seymour. To this end, he had various trumped-up charges brought against Anne, including adultery, incest, and intended regicide. Being a decent cove, however, he graciously permitted her head to be severed by an expert swordsman.

Anne of Cleves, Queen of England (1515-57)

Anne of Cleves, Queen of England (1515-57)

After Jane Seymour’s death, Henry VIII decided to strengthen his alliance with German Protestants by marrying one of the Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg’s two daughters. Hans Holbein the Younger was famously sent to paint accurate portraits of both so that Henry could make his choice. When in 1540 the King informally met his bride-to-be Anna von Kleve at Rochester Abbey, however, he was sorely unimpressed. The feeling remained when they were officially introduced at Blackheath; and he proved incapable of consummating their marriage at Greenwich. After six fruitless months, he got her to agree to an annulment. The ever-loyal Thomas Cromwell, who had presided over the fiasco, paid with his life. At least Anne was treated well: Henry called her his “Beloved Sister”, and granted her the use of several houses, including Hever Castle. She resided last at the Manor House in Dartford, where she outlived all Henry’s other wives, and indeed him.

Katherine Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk (1519-80)

Katherine Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk (1519-80)

In 1516, Baron Willoughby de Eresby married Maria de Salinas, Catherine of Aragon’s Spanish companion. He died in 1526, whereupon Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, purchased their only child Katherine’s wardship, and contrived to deny her uncle’s claim to Willoughby’s vast Lincolnshire estates, even invoking Cardinal Wolsey. When Brandon’s third wife died in 1533, he married the girl, despite a 35-year age difference, and so acquired the estates himself; but he expired in 1545. Katherine loyally supported the King’s English Reformation, so he designated a chamber at Otford Palace ‘My Lady of Southfolk’s lodging’; his death spared her becoming his seventh wife. When his sixth, Catherine Parr, died in childbirth, Katherine resented being appointed the orphan’s guardian; the baby promptly disappeared. Both her sons by Brandon having died young, she fled overseas with her second husband during Mary I’s reign, their exile being recounted in ‘Foxe’s Book of Martyrs’. She died back in Lincolnshire.

Sir Henry Sidney (1529-86)

Sir Henry Sidney (1529-86)

Sir William Sidney from Yorkshire was a favourite of Henry VIII and Edward VI, whose services were rewarded with estates that included Penshurst. His son Henry was altogether more controversial. In 1565, he was made Lord Deputy of Ireland. Arriving to find considerable disarray, he managed to secure Elizabeth I’s permission to eliminate the insurgent Shane O’Neill, whom he held responsible. He then travelled south and north bending other chieftains to his control. Although his brutality was nothing unusual for the era, his administrative initiatives included ‘lord presidents’ to exercise military authority over southern Ireland, which provoked the Desmond Rebellions. He left Ireland in 1571, convinced that Elizabeth was insufficiently grateful. He returned in 1575, but his annual levy prompted protests to her from his peers in Ireland. In 1578, he was recalled in disgrace, and whiled away the rest of his life on the Welsh borders. His one lasting accomplishment was siring the great poet Sir Philip Sidney.

Thomas Sackville, 1st Earl of Dorset (1536-1608)

Thomas Sackville, 1st Earl of Dorset (1536-1608)

Thomas Sackville was born at his family’s ancestral home at Buckhurst, Sussex, and ended up owning both Knole House and Groombridge Place among many other properties. His wealth derived from an eventful career in diplomacy, involving missions to Rome (where he was gaoled), France, and the United Provinces. Surprisingly, he has a place in literary history as well. He co-wrote ‘The Tragedie of Gorboduc’ (1561), the bloody tale of what happens when a king divides his patrimony between his two sons, Ferrex and Porrex, whose mutual enmity has dire consequences; suffice it to say (spoiler alert) that everyone dies. Sackville’s co-author Thomas Newton wrote the first three acts and Sackville covered the last two. It was performed before Elizabeth I in 1561, and at Dublin Castle forty years later became the first play to be performed in Ireland. The first ever blank verse drama in English, it was a direct antecedent of ‘King Lear’.

William Lambarde (1536-1601)

William Lambarde (1536-1601)

Lambarde, a prominent draper’s son, was born in London, though the family home was West Coombe Manor east of Greenwich; he inherited it at 18. After entering Lincoln’s Inn and studying Old English and History, he was encouraged at 32 to write a compendium of Anglo-Saxon laws, called ‘Archaionomia’. Two years later, he completed the manuscript of his most popular work, a weighty tome entitled ‘A Perambulation of Kent: conteining the Description, Hystorie, and Customes of that Shyre’. A model of organisation, it was the first ever such county study. He planned to expand it into a series covering the country before learning that it had already inspired William Camden to commence his own famous ‘Britannia’. A fair-minded JP, Lambarde established a charity, the College of the Poor of Queen Elizabeth, providing almshouses near his home. Late in life, he become Keeper of the Rolls, and won the Queen’s confidence. His three successive wives were all of Kentish stock.

Edward VI, King of England (1537-53)

Edward VI, King of England (1537-53)

For one whose birth was greeted with such an outpouring of joy, the life of Edward VI was strangely disappointing. He never got to know his mother, Jane Seymour, because she died suddenly a fortnight after giving birth to him at Hampton Court. He succeeded his father Henry VIII at the age of nine. The Council ruling on his behalf functioned calamitously, ushering in military defeat, economic problems, and revolt. Only in religious reform did his reign see anything coherent. The young Protestant king oversaw a radical advance in the Reformation, as Archbishop Cranmer and Bishops Latimer and Ridley established the Anglican liturgy. Conscious that his half-sister Mary would not stomach the new orthodoxy, Edward worked with the Council to bar her from power, issuing his ‘Devise for the Succession’ in 1553. By that time, however, he had contracted a fatal lung illness, possibly tuberculosis. He resorted to the Placentia Palace in Greenwich, where he died aged 15.

Jane, Queen of England (1537-54)

Jane, Queen of England (1537-54)

Even by Tudor standards, the fate of Lady Jane Grey was dismal. Like Edward VI, she was descended from Henry VII, but through a cadet branch. Living at Halden Place in Rolvenden, she seemed secure from courtly intrigue. In May 1553, she married Guilford Dudley, the Duke of Northumberland’s son, in a triple wedding. The King, however, was fatally ill, and a month later reversed his father’s Third Succession Act that had restored Edward’s two illegitimate sisters to the succession. By July, he was dead, and Lady Grey became Queen Jane. When her father-in-law belatedly rode off to apprehend Edward’s elder sister, Mary Tudor, the Catholic Earl of Arundel staged a putsch. Mary was hailed queen, and Jane’s support evaporated. Since Jane hadn’t wanted the job, Mary showed clemency at first; but when her father joined Wyatt’s Rebellion, the Nine-Days’ Queen was done for. Young Jane was even shown Dudley’s headless body before facing the chop herself.

Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton (1540-1614)

Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton (1540-1614)

When he was just seven, Howard’s father Henry, the Earl of Surrey, provoked Henry VIII by incorporating Edward the Confessor’s arms in his own. Though legally entitled to, he was found guilty of treason, and so became the paranoid king’s last victim; his own father survived because the king died on the very day that his execution was slated. Young Howard was suspected of Catholic sympathies throughout his life, which cost him more than once in terms of preferment; but he compensated with his reputation for learning and numerous shows of philanthropy, including Trinity Hospital at Greenwich. He also built Northumberland House and Audley House, and owned Greenwich Castle, which he modernised and lived in from 1605 after being made Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports and Earl of Northampton the previous year. This showy do-gooder turned out to have a dark side, however, when it was discovered posthumously that he had been an accomplice to a political murder.

Sir Francis Drake (~1540-96)

Sir Francis Drake (~1540-96)

Drake’s bravado at sea earned him the ultimate accolade, the contemptuous Spanish nickname ‘El Draque’ – The Drake. The quintessential English national hero, his story used to be known to every schoolchild. In an era of Spanish mastery of the seas, he plundered the Spanish Main, burned King Philip II’s fleet at Cadiz, and enjoyed a game of bowls before seeing off the Armada. Less well known is his Kentish connection. His family had fled a Catholic rebellion in their native Devon when he was nine, settling at Upnor, where his father became vicar. It was their proximity to the Medway that first drew Drake to seafaring. It is often forgotten that Queen Elizabeth knighted Drake at Deptford not for his military exploits but as a navigator. He was in fact the first man ever to captain a ship all the way around the world. For an encore, he even claimed California as an English colony en route.

William Camden (1551-1623)

William Camden (1551-1623)

A Londoner by birth, Camden went to Oxford, where he earned no degree but did get to know Philip Sidney, who encouraged his antiquarian interests. At 26, he embarked on his marquee project: ‘Britannia’, a survey of the British Isles written in Latin. It involved travelling all around the country, as well as borrowing from sources like Leland and Lambarde. It took him thirty years to complete, the last edition being much expanded from the first and including the first ever set of county maps. In addition to being appointed headmaster of Westminster School, he created several other useful records, from ‘Annales’ – the first history of the Elizabethan era – to a collection of English proverbs. He moved in 1609 to Chislehurst, where his home was posthumously renamed Camden Place. ‘Britannia’ remains a landmark antiquarian study, and Camden’s name is recalled in the Camden Chair he established at Oxford, the Camden Society, and (indirectly) the London borough.

Edmund Spenser (~1552-99)

Edmund Spenser (~1552-99)

Spenser must be acknowledged as one of the most talented (not to mention prolific) poets in the English language. On the other hand, he was a world-class toady. Born in London, he made his way via the Merchant Taylors’ School to Pembroke College, Cambridge. The Master there was John Young, who later became Bishop of Rochester. In 1578, Young invited Spenser to join him as secretary. Thereafter, Spenser spent many years in Ireland. He was not popular, possibly because of his view that Ireland would never be subjugated until its language and culture had been obliterated; Irish insurgents eventually burnt his home. While there, however, he wrote the first three volumes of his masterpiece, ‘The Faerie Queene’. It was intended to be a 12-volume apotheosis of Queen Elizabeth I. Although it won him a £50 pension, he managed only six volumes, which probably cost him his knighthood. It is not known whether the Queen read it.

Richard Hooker (1554-1600)

Richard Hooker (1554-1600)

Although not from a wealthy family, Hooker showed such intellectual promise at Exeter Grammar School that the Bishop of Salisbury secured him a place at Oxford. He was ordained in 1579, and proved himself a lucid thinker on theological matters in troubled times. After being drawn into a robust dispute with the Puritan theologian Thomas Cartwright, he was offered the living of Boscombe in Wiltshire, allowing him to devote himself to his eight-volume ‘Of the Lawes of Ecclesiastical Politie’ (published 1594-1662), which constituted the first serious theological treatise in English. Intended as a rational refutation of Puritanism, it provided the basis for future Anglican thought. He spent his last five years as rector of both St John the Baptist in Barham and St Mary the Virgin in Bishopsbourne. He was buried in the chancel of the latter, and bequeathed its current pulpit. The poet William Cowper later dedicated a memorial to him there.

Isaac Casaubon (1559-1614)

Isaac Casaubon (1559-1614)

The son of a French Huguenot couple, Casaubon spent his first two decades evading Catholic persecution. Having first learned Greek while hiding out in a cave after the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre (1572), he ended up a professor of Greek in his Calvinist birth-city, Geneva. His scholastic prowess led him to edit and commentate on several Greek writers, his greatest contribution being Athenaeus’s ‘Deipnosophistae’, an important source of knowledge of ancient Greek life. Much sought after as a scholar, he even found employment in a French university, before settling in Paris. When the supportive French king was assassinated by a Catholic radical in 1610, however, Baron Wotton of Marley took Casaubon to England. Instantly welcomed as an Anglican seeking a middle way between Catholicism and Puritanism, he was awarded a prebendal stall at Canterbury. Although on good terms with the likes of Erasmus, he still encountered bigotry from xenophobes and Jesuits, but remained and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

Sir Edwin Sandys (1561-1629)

Sir Edwin Sandys (1561-1629)

The son of the Archbishop of York, politician Edwin Sandys from Worcestershire is remembered as the first to pen the maxim “Honesty is the best Policy”. In reality, however, he appreciated that the best way to advance his rebellious leanings was to suck up to the monarch, James I, while pressing ahead quietly with the development of Virginia on broadly republican principles. Having succeeded Thomas Smythe as treasurer of the Virginia Company in 1619, he promoted ‘indentured servitude’, a means for migrants to work off their transport to America and living costs, and facilitated the grant of land for settlers to farm. He also supported the Pilgrim Fathers in Massachusetts with a generous £300 loan. Meanwhile, he moved to Northbourne near Deal, where he served as MP for Rochester, for Sandwich, and for Kent, and then died and was buried. His second son Edwin, a Parliamentarian enforcer, would prove an altogether less delicate operator in the Civil War.

Henry Brooke, 11th Baron Cobham (1564-1618)

Henry Brooke, 11th Baron Cobham (1564-1618)

Henry Brooke was perfectly happy as the 11th Baron Cobham and Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports when a regime change wrong-footed him. Brooke was the son of the 10th Baron, the man reckoned to have been the basis of Shakespeare’s Falstaff, whom the Bard originally named Oldcastle after Brooke’s ancestor. Henry’s brother Sir George, an altogether sharper character, was involved in a plot to kidnap the new Catholic king, James I, and replace him with Arbella Stuart. This so-called ‘Bye Plot’ was discovered, and Sir George executed. The investigation also revealed a ‘Main Plot’ in which his brother, Henry, was to travel to Spain, collect a vast amount of money, and share it with Sir Walter Raleigh for seditious purposes. Brooke’s understandable motivation was probably to stop the King stealing his estate to give to a Scottish favourite, the Duke of Lennox. Both Brooke and Raleigh spent most of the rest of their lives in the Tower.

John Donne (1572-1631)

John Donne (1572-1631)

A Londoner, John Donne was born Catholic in a Protestant society. Faced with limited career prospects, he spent his substantial inheritance on women and travel. At length he landed a job as secretary to Sir Thomas Egerton, whose daughter he married secretly, for which he was initially thrown in gaol. Living in poverty with numerous children drove him to despair. He sought respite in politics; but it was poetry that changed his life. He started writing poems for wealthy patrons, including anti-Catholic works. His expedient transformation was completed in 1615, when he became an Anglican priest and took on the rectory of Sevenoaks. It’s uncertain how often he preached there, especially after becoming Dean of St Paul’s, where he eventually was buried. One of the tricksy Metaphysical poets, his erotic and satirical works later gave way to religious reflection. Most famously, his ‘No man is an Iland’ invites us to regard every death as our own, presumably even his.

William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury (1573-1645)

William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury (1573-1645)

Little remembered today except by historians, William Laud has a place in history as the Archbishop of Canterbury tried and executed by Parliament. The son of a clothier in Berkshire, he went to Oxford, and was ordained at 27. A vehement anti-Protestant of notable learning and industry, he acquired the patronage of such politically unsavoury figures as the Earl of Devonshire and the Duke of Buckingham, in addition to a plethora of lucrative benefices that culminated in the Archbishopric in 1633. He was a godsend to Charles I, for whom he assiduously set about asserting Catholicism within the English Church and rooting out Puritanism. This ultimately provoked the sitting of the Long Parliament that in 1640 impeached him. Having declined to attempt escape from the Tower, he was tried by peers and found guilty of endeavouring to overthrow Protestantism and undermine Parliament. Though this did not constitute treason, he was beheaded on Tower Hill anyway.

Anne of Denmark, Queen of Scotland & England (1574-1619)

Anne of Denmark, Queen of Scotland & England (1574-1619)

When James VI of Scotland needed a wife, he had few options, and settled for 14-year-old Princess Anna of Denmark. A Protestant, she was advised by Elizabeth I of England to keep her nose clean by shunning Catholicism – advice she appears secretly to have disregarded. In 1603, James inherited the English throne, and overnight became a serious international player. By then, however, the two had grown apart, and not only because of James’s greater attachment to the Duke of Buckingham. Anne was noted as much for her shrewishness as her avarice, which drove the King to distraction. He held her apart from their son Prince Henry, who was kept at Charlton House while she resided nearby at Placentia Palace. Most of her children died young, including two girls she bore at Greenwich, while Princess Elizabeth made a disappointing match; so, when Henry expired at 18, it left only the disastrous Charles. The King was not at Anne’s funeral.

George Sandys (1578-1644)

George Sandys (1578-1644)

In 1621, George Sandys, youngest son of the Archbishop of York, sailed away with his niece’s husband, Francis Wyatt of Boxley Manor, to take up positions as respectively the Virginia Company treasurer and the colony’s governor. Sandys remained for about a decade before returning to England. One of his two loves was literature. He had already translated Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses’ in verse and begun Virgil’s ‘Aeneid’; he also translated or paraphrased several religious works. The other love was travel, which took him on an extensive tour of the eastern Mediterranean. He combined his two passions by writing travelogues that provided valuable insights into Italy, Egypt, the Holy Land, and the Ottoman Empire, which his eldest brother Samuel had also visited. Four volumes of his ‘The Relation of a Journey began A.D. 1610’ were published together in 1673 as ‘Sandys Travels’, containing dozens of images and maps. He died unmarried at Boxley.

Jacob Astley, 1st Baron Astley of Reading (1579-1652)

Jacob Astley, 1st Baron Astley of Reading (1579-1652)

Astley, from Norfolk, began his military career at 18 in celebrated company, accompanying Sir Walter Raleigh and the 2nd Earl of Essex on an ill-fated adventure against Spain. Following his more successful participation in the Dutch Revolt, he served Christian IV of Denmark with distinction in the 30 Years’ War. He was then hired by the former King Frederick of Bohemia to act as military tutor to Prince Rupert of the Rhine, by whose uncle, Charles I, Astley was knighted in 1624. He commanded the Royalist infantry alongside Rupert’s cavalry at the battle of Edgehill (1642) that commenced the Civil War in earnest; and, having been rewarded with a barony, he remained in charge until the last pitched battle before the King’s arrest. He was eventually permitted to retire to the Archbishop’s Palace at Maidstone, which he had inherited; but, true to his word, he took no part in the 1648 battle. He is commemorated in All Saints Church.

Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex (1591-1646)

Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex (1591-1646)