Leeds Castle, C18

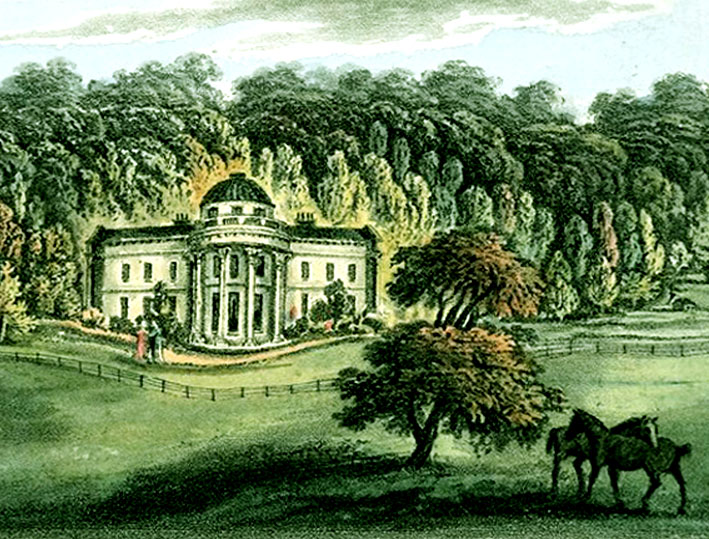

Acrise Place

Acrise Place

Like Tudeley in West Kent, Acrise near Folkestone is a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it hamlet that nevertheless possesses some architectural interest, most prominently in the form of Acrise Place. Its name is not that of some Norman invader but a corruption of ‘oak rise’, a name befitting the local terrain. The original north-facing house was built in the C16, expanded with a second range back-to-back in the C17, and reworked in the C18. In 1666, it was acquired by the merchant Thomas Papillon, a Dover MP who was active in national politics after the Restoration. It remained in his family until 1850 before passing through other private hands. In WW2, while occupied by the Army, it witnessed in its grounds the fatal crash of a Hurricane whose pilot was attempting to destroy a doodlebug. It was purchased by developers in 1986, who converted the two ranges into Acrise Place and Acrise Court, and sold off the outbuildings as more residences.

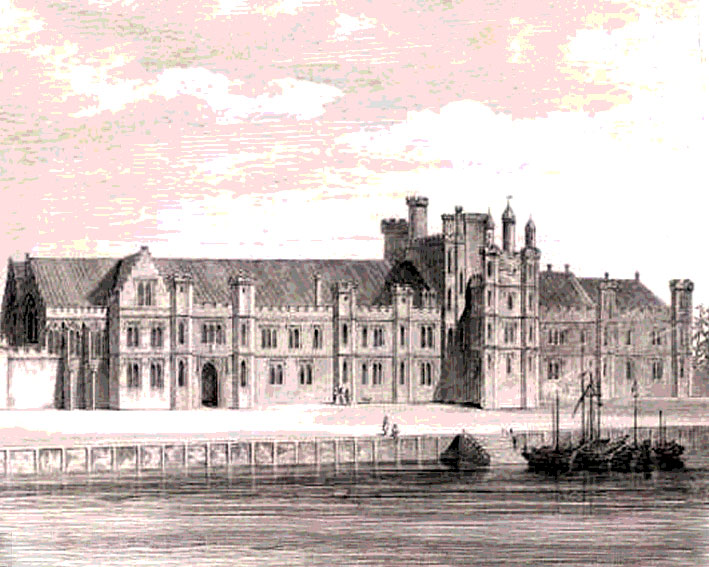

Allington Castle

Allington Castle

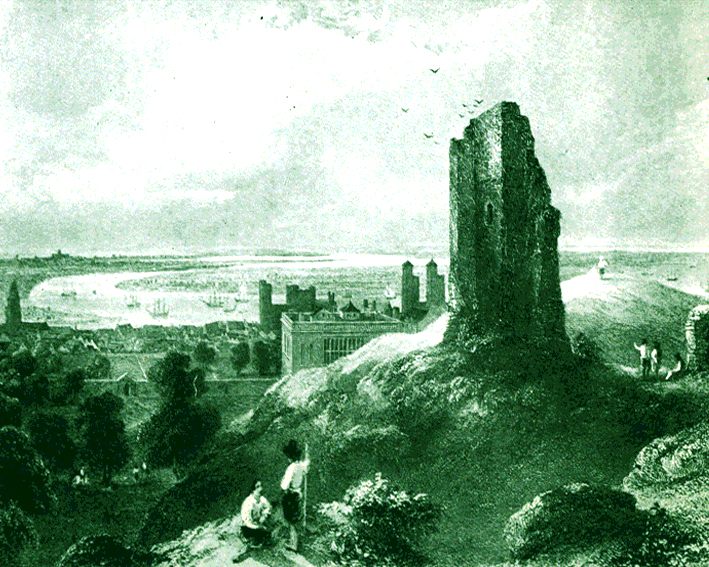

The original occupant of the bend in the River Medway one mile north of Maidstone was a so-called adulterine castle, built without royal approval during the C12 Anarchy. It was torn down and briefly replaced by a manor house before the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports commissioned today’s castle at the end of the C13. In 1492 it famously fell into the possession of the Wyatts, the rebellion against Bloody Mary being hatched there in 1554. After Sir Thomas Wyatt’s execution, it suffered centuries of decay, not to mention two serious fires. But for the intervention of locals, it would have been demolished. Eventually, in 1905, it was purchased by Lord Conway, who spent 30 years restoring it. The Castle was sold in 1950 to the Carmelite Friars of Aylesford Priory, and remained a religious establishment until 1999. It is now home to the American-born founder of MORI and TV pundit, Sir Robert Worcester.

Angley Park

Angley Park

Angley House, just south of Cranbrook, must once have been a special place to live or visit. It dated back to the Norman era, when a manor was granted to the Abbot of Battle by William I himself; its ownership remained unchanged until the Dissolution of the Monasteries. In the C18, it was said to have a chalybeate spring, and trees surviving from the Andredes Weald. In the early C19, it was upgraded to Regency style, and by mid-century boasted gardens, a lawn, a shrubbery, walks, an orchard, a nursery, fish ponds, and a lake, all inside a beautiful park. After that, however, it went sharply downhill. It was replaced around 1870 by a Victorian edifice of little architectural merit, which in turn gave way in 1931 to a smaller house set in 35 acres; the rest of the 825-acre estate was sold off in 43 lots. Fortunately, the delightful Angley Wood nearby is still open to the public.

Archbishop’s Palace, Charing

Archbishop’s Palace, Charing

Though the heritage site in Charing has its origins in the C8, construction of the present palace started in the late C13, and it was substantially rebuilt 200 years later. The Church would eventually own many such palaces, serving as short-term residences for the Archbishop on his travels between Canterbury and London; Charing’s was the first. Its finest hour arrived in 1520, when King Henry VIII and his wife Catherine of Aragon stayed on their way to meet King Francis I of France at the Field of the Cloth of Gold, in an effort to make warfare history. The locals must have been overwhelmed when the King’s retinue of five thousand turned up on their doorstep. He later confiscated the palace during the Dissolution of the Monasteries; it was leased and then sold to gentleman farmers, under whom it deteriorated badly. Efforts to purchase and restore it as a public utility have stalled.

Archbishop’s Palace, Maidstone

Archbishop’s Palace, Maidstone

The east bank of the Medway next to the confluence of the Len, near the centre of Maidstone, is one of the best pieces of real estate in Kent. No wonder that an episcopal manor stood there even in Anglo-Saxon times. The much grander Archbishop’s Palace that superseded it was ordered by Archbishop Ufford in 1348 as a convenient stopover. The palace was expanded in the following century, by which time the Tithe Barn, All Saints Church and the College had been added to the east and south-east. After the Reformation, its purpose became purely secular. Henry VIII gifted it to Sir Thomas Wyatt the Elder, but his daughter Mary I confiscated it following the rebellion led by Wyatt’s son. After passing to the Astley family in the C17 and the Marshams in the C18, it devolved to a Territorial Army medical school and ultimately, under the management of Kent County Council, a registry office.

Ashurst Park

Ashurst Park

Ashurst, near the Sussex border west of Tunbridge Wells, first appeared in records as one of scores of manors granted by William I to Geoffrey de Peverell in reward for his contribution to suppressing their new English vassals, notably with castle-building. Over the centuries, it passed through numerous hands, until in the C16 it was occupied by the dramatist Thomas Sackville, Earl of Dorset. Although a number of random buildings stood there in the early C19, it was not until the 1820s that William Fowler-Jones bought land there to build the basis of today’s impressive stucco house. Subsequently much expanded, it was sequestrated by the armed forces in WW2 before becoming home to Wykeham Cornwallis from Linton Place, who died there in 1982. It was briefly a rest home, Fernchase Manor, but returned to its former name and use under new private ownership. Having received an extravagant makeover, it was recently on the market for £10,000,000.

Barham Court, Teston

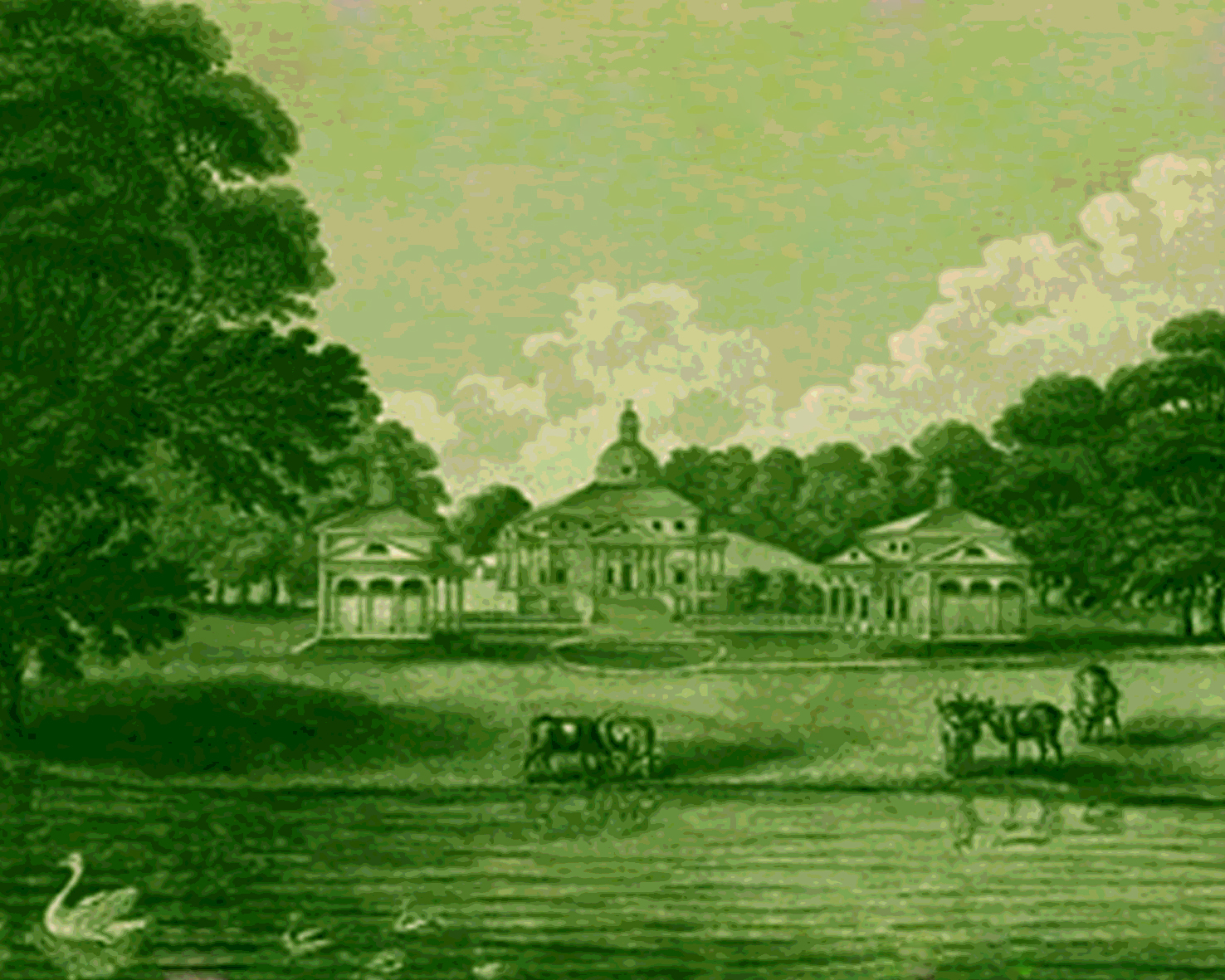

Barham Court, Teston

Although one of Kent‘s lesser known stately homes, Teston’s Barham Court has a lot of history. The house on the estate in the C12 was owned by Sir Reginald FitzUrse, who legendarily fled to Ireland after leading the assassination of Thomas Becket. His kinsman Robert de Bereham, from Barham near Canterbury, subsequently took over the property. It was acquired four centuries later by the Boteler family, who in the C17 supported the Stuart monarchy. The 1st Baronet of Barham Court, William Boteler, was jailed for supporting the Kentish Petition of 1642, and killed in battle two years later; the house was meanwhile ransacked. It was acquired in the C18 by Charles Middleton, 1st Baron Barham, and became the headquarters of the Testonites, the anti-slavery lobby that regularly welcomed William Wilberforce as a guest. The house was used as a military hospital during WW1, and suffered a serious fire in 1932. It is now given over to commercial and residential properties.

Bayham Hall

Bayham Hall

The story of Bayham Hall begins in 1714, when the estate belonging to the long-ruined Bayham Old Abbey was sold to the Lord Chief Justice Sir John Pratt, whose younger son Charles became the 1st Earl Camden. The living quarters at the time were on the site of the current Dower House, which was soon expanded and glorified. In 1799, the 2nd Earl Camden had plans drawn up for a much grander house with a lake. The lake was built, but nothing done about the house until 1870, when the 3rd Marquess Camden erected today’s grand construction up the hill half a mile to the north-east, together with formal gardens. In 1961, the 5th Marquess released the Abbey ruins to the state, and in the 1970s Bayham Hall and 40 acres were sold off. An internet entrepreneur, Justin Cooke, bought the Hall in 2002, and his wife refurbished the interior. One wing is now commercially available for film productions.

Beachborough Manor

Beachborough Manor

The Beachborough estate north-west of Folkestone was once one of the largest in Kent, enjoying expansive pasture and ornate gardens. The Manor was occupied for generations by the Brockman family, whose most notable scion was the Sir William Brockman who marshalled Royalist troops in the defence of Maidstone against the Roundhead general Fairfax in 1648. The current Georgian house, surrounded by Beachborough Park, was built in 1813. David Lloyd George lived there in the early part of the C20, and it was made available to the Canadians during WW2 as a military hospital conveniently situated near the Channel coast. The estate is now the residence of the Wallis family, of whom the paterfamilias Gordon Wallis is a noted former football-club chairman and collector of sporting memorabilia. Being located five minutes’ drive from the Eurotunnel terminal that opened in 1994, it also offers handy bed-and-breakfast accommodation.

Belmont House

Belmont House

The original house was built on a greenfield site at Throwley in the 1770s. It was expanded two decades later by new owner Captain John Montresor, who had retired from the Army after serving in the American Revolutionary War. Montresor was jailed for fraud, however, and Belmont was confiscated by the state. His loss was the nation’s gain in more ways than one. The estate was bought at auction in 1801 by General George Harris, who 14 years later became the 1st Baron Harris of Belmont. He founded a distinguished dynasty: the 3rd Lord Harris would create the united Kent County Cricket Club in 1870, the 4th would be Governor of Bombay and captain of England, and the 5th founded the Antiquarian Horological Society. It was the last who left the most striking reminder of his tenure, a magnificent collection of 340 clocks. The house and grounds, now in the hands of a trust, are open to the public.

Belvidere

Belvidere

Belvedere, meaning ‘beautiful view’, is a curious name for the urban sprawl north-west of Erith. It derives from a house called Belvidere that could truthfully make that boast both inside and out. Built in the early C18, it was bought in the 1750s by banker Sampson Gideon, who rebuilt it as a grand brick affair with an impressive stone portico. On the inside was an extraordinary display of artworks, including busts of Dryden, Milton, and Shakespeare, and a collection of paintings of the highest quality. In the Blue Drawing-Room alone hung works by Brueghel, Rubens, Veronese, and da Vinci, among many others, while in the dining-room was a self-portrait by Rembrandt along with two Canalettos. The surrounding estate was richly wooded and adorned with well-manicured gardens, presenting a fine view of the Thames. The house was converted from 1865 to a merchant seamen’s retirement home, but demolished in 1958 for residential development. Only the Frank’s Park woodland survives.

Betteshanger Park

Betteshanger Park

Nowadays, Betteshanger House west of Deal is home to a prestigious pre-prep boarding school called Northbourne Park. The impressive building that houses its nearly 200 pupils was preceded by a much humbler villa built by Robert Lugar in 1829 for Frederick Morrice. In 1850, Sir Walter James, the 1st Lord Northbourne, bought the 80-acre estate and had Anthony Salvin (of Scotney Castle fame) perform alterations. After serving as Sheriff of Kent in 1855, Northbourne commissioned architect George Devey to transform it into the sort of towering, expansive L-shaped affair it is now – a process that took him 30 years. Betteshanger underwent a dramatic transformation in the late 1920s with the arrival of the Kent Coalfield, at which point it declined from rural village to pit town. When Northbourne’s grandson, the 3rd Baron, died in 1932, his son and daughter-in-law decided not to stay, but let the house to the new prep school.

Bifrons

Bifrons

Derived from the Roman god Janus, Bifrons was a two-faced monster in demonology, ‘bifrons’ being the Latin for two-faced; but the name of Bifrons Place in Patrixbourne simply alluded to the sprawling house’s two very different facades. It was built by 1611 for John Bargrave, a staunch Royalist, sold by his grandson in 1662, and purchased in 1694 by Sandwich MP John Taylor, whose grandson Edward replaced it with a much simpler neoclassical contruction. After driving past Bifrons in 1796, Jane Austen recalled having “doated” on Edward’s son. In 1830, George IV bought it for his final mistress Marchioness Conyngham, who lived there until she died at 91 in 1861. It remained in her family but, like many grand houses, was occupied by the military during WW2, and fell into such disrepair that the family demolished it in 1948. Bifrons’ name now graces only a hill and an unprepossessing housing development.

Bleak House

Bleak House

Fort House in Broadstairs was built at the turn of the C19, shortly before the Napoleonic Wars, and doubled in size a hundred years later. This four-storey construction, which still dominates the promontory at the northern end of Viking Bay, was home to the captain of the defensive fort at that location. It became Charles Dickens’ preferred choice for holidays in his thirties, and it was there that he wrote ‘David Copperfield’ in the late 1840s. It certainly was not the inspiration for ‘Bleak House’, which was set in St Albans; but the fact that the novel of that name was his next perhaps inspired locals to refer to Fort House as ‘Bleak House’ in jest. The name stuck. Though still a domestic residence, the property long housed a museum on the lower ground floor, and the bed-and-breakfast offering was popular with Dickens fans going to soak up the Victorian atmosphere.

Boughton Monchelsea Place

Boughton Monchelsea Place

A manor house stood next to Boughton Monchelsea church as early as 1214. It passed through numerous hands before being bought by Sir Thomas Wyatt of Allington Castle. Wyatt’s son, the famous rebel, sold it to a fellow conspirator, Robert Rudston, from whom it was sequestrated by Queen Mary after the revolt. Queen Elizabeth I restored it to him, however, and around 1570 he constructed what would become the basis of the present building. After the death of Rudston’s sons, the house was acquired by Maidstone MP Sir Francis Barnham in 1613. For nearly three centuries it passed by inheritance through generations of the Burnhams and then, by marriage, to the Riders, who together supplied a number of other local MPs. From 1903 it was occupied by the Winch family, who sold it in 1998 to the current owners, the Kendricks. It is occasionally open for special events, when visitors can enjoy its stupendous views across the deer park.

Boughton Place

Boughton Place

The former Bocton Hall is strategically placed next to St Nicholas’s Church at the top of the hill in Boughton Malherbe, commanding fine views all around. There was a fortified manor on the site as from the 1340s, which passed by marriage into the possession of Nicholas Wotton, twice Lord Mayor of London. In 1568 it was the birthplace of diplomat and politician Sir Henry Wotton. Much of the manor was demolished and replaced by the current structure in the C16, with further alterations in the C19. Between 1683 and 1750 it was owned by a succession of Earls of Chesterfield, but was then bought by Galfridus Mann, whose son Sir Horatio Mann would also inherit a rather grander home, Linton Hall. Catherine Mann’s marriage to James Cornwallis left both houses in the possession of the Earls Cornwallis until Boughton Place was sold in 1922. It is still privately owned.

Bourne Place

Bourne Place

Now known as Bourne Park House, Bourne Place was built in 1701 halfway between Bridge and Bishopsbourne. The widow of Royalist Sir Anthony Aucher had a new red-brick mansion constructed for her young son, Sir Hewitt, to replace their dilapidated current home. Her descendants sold it in 1844 to Matthew Bell, who leased it to, among others, Sir Horatio Mann of Boughton Place. In 1765, Mann invited Leopold Mozart and his family to stay for a week. An avid cricketer, he also constructed Bourne Paddock in the grounds, where he staged top-rank cricket matches over a period of a quarter-century. The house and its 57-acre estate passed through several pairs of hands thereafter, suffering long periods of neglect. The current owner, the aristocratic mother-in-law of Jacob Rees-Mogg, owns the priceless Fitzwilliam Art Collection, little of which is ever released for exhibition. The residual nine acres of gardens, incidentally, contain one of several ‘icehouses’ in Kent, the C18 predecessor of a freezer.

Boxley Manor

Boxley Manor

During the Anarchy (1139-54), King Stephen employed the military services of the mercenary William of Ypres, who was granted custodianship of all Kent from 1141 until 1157, early in the reign of Henry II. He built an abbey at Boxley in 1146 that was occupied by Cistercian monks from south-east of Paris; it survived until the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1537. In the meantime, it earned a reputation for extraordinary venality, making money not only out of the dodgy St Rumwold effigy and Rood of Grace, but also a supposed finger of St Andrew that was pawned off for £11 when worshippers stopped coming to see it. In 1540, Henry VIII gifted the abbey to Sir Thomas Wyatt the Elder, whose descendants continued to live in the still habitable part of the building. Not much survives today, apart from a splendid barn (the former hostel) and its poignantly ruined gates on Tyland Lane.

Bradbourne House

Bradbourne House

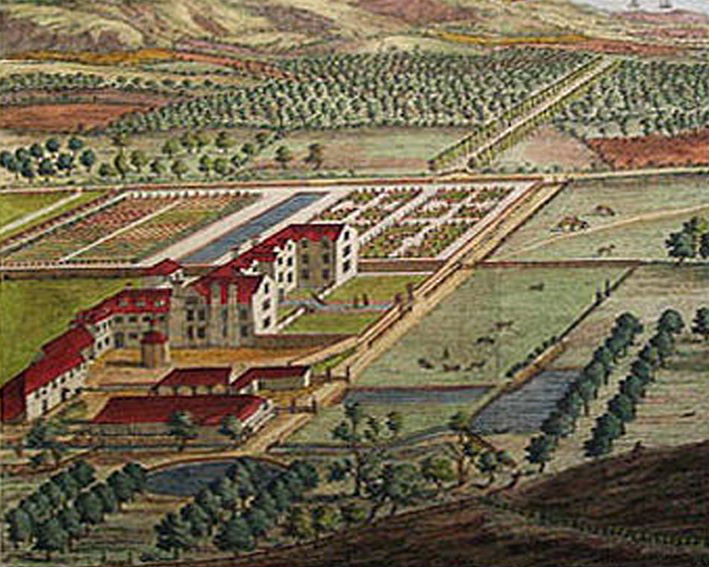

The waterside site just north of East Malling was occupied as early as Roman times. The Tudor house built there was substantial, and may have been moated. It was sold around 1656 to a prominent judge, Thomas Twisden, who was later knighted. He expanded the estate to create Bradbourne Park, and his son had the road diverted away from the house. From 1712 to 1715, another Sir Thomas Twisden built the current house, incorporating some features of the original. Although further improvements were made over the next hundred years, the Twisdens neglected it thereafter. When the last of the line, Sir John Twisden, died in 1937, the property was sold to the body from which the East Malling Trust for Horticultural Research was derived, serving as an administrative centre for the adjacent East Malling Research Station. Considerable money and effort have since been spent on restoring the house, which can now be hired for special events.

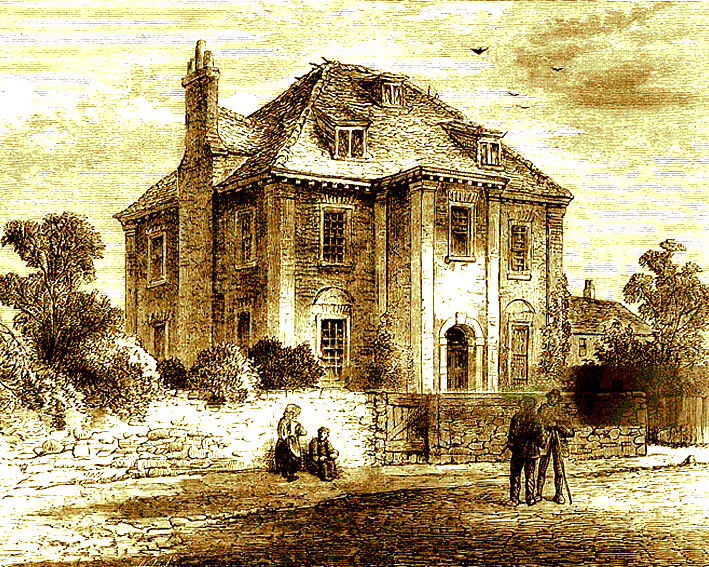

Bridge Place

Bridge Place

Around 1638, a large house was built at Bridge on the site of a medieval manor. The owner, Arnold Braemes (1602-81) from Dover, was an uninhibited socialite, and had the house constructed on such a magnificent scale that in East Kent it was the second only to Chilham Castle. It attracted numerous personalities, and was painted by more than one Dutch artist. Knighted by the future king as he was returning from exile in France in 1660, Sir Arnold lived well beyond his means, and his heirs were obliged to sell the house in 1704 to John Taylor, owner of neighbouring Bifrons. For reasons unknown, but possibly out of spite, he had the majority torn down, leaving just one admittedly spacious wing. Restored after WW2, it enjoyed a renaissance in the 1960s as a music venue that hosted the likes of the Kinks, Led Zeppelin, and Manfred Mann. Since 2019, it has been a boutique hotel.

Bromley Palace

Bromley Palace

As early as the C8, Aethelberht II of Kent granted land in Bromley to the Bishop of Rochester, to which further additions were made in later centuries by both gift and sale. After Odo had failed to appropriate the estate in the wake of the Norman Conquest, a manor house was built for the bishopric, the land being little good for farming. It must have been meagre, because it was rebuilt on a grander scale within decades. The estate was confiscated and sold during the Civil War, but restored to the bishopric in 1660, and entirely replaced in 1774. It was finally sold in 1845 to a baronet, Coles Child, whose family made repeated improvements. After WW1, it became a school, and then a college. Finally, in 1980, the council moved in and turned it into Bromley Civic Centre. The grounds, though now much diminished, still contain a lake, artificial rockeries, and even a folly.

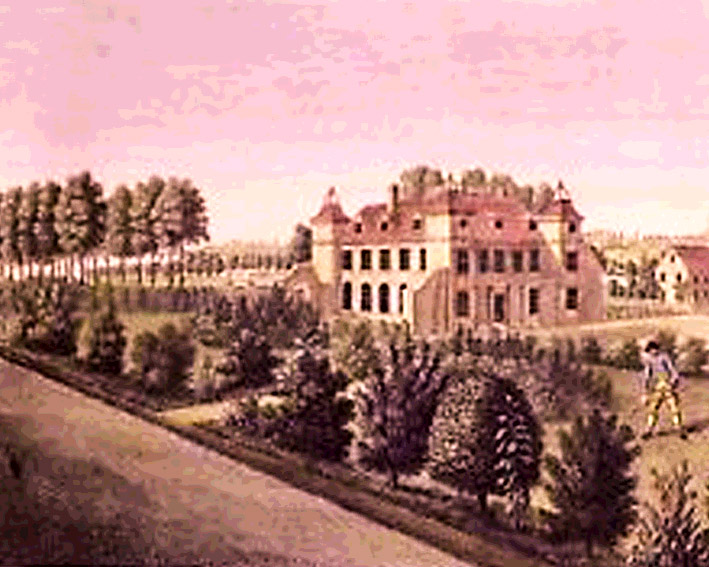

Broome Park

Broome Park

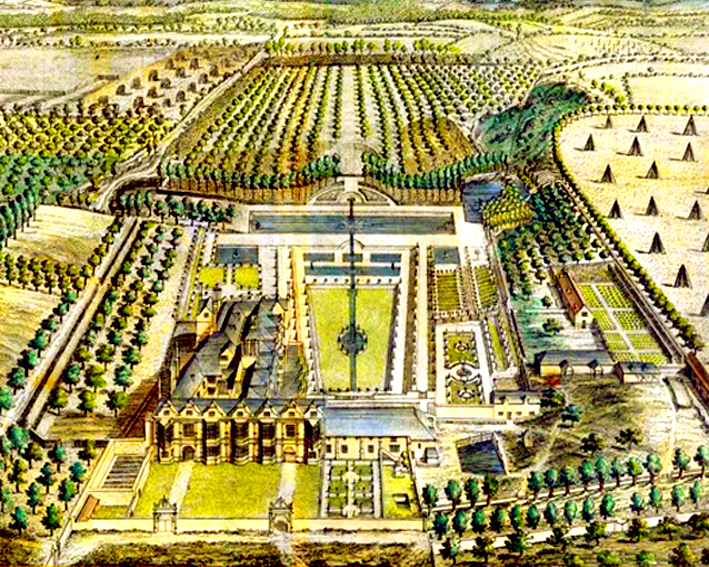

The MP for Hythe, Sir Basil Dixwell, had the house built in 1635 off the Canterbury road in Barham. The estate remained in his family for nearly 300 years. It was sold in 1911 to Lord Kitchener of Khartoum, who undertook major works including re-laying the gardens. Thereafter, Broome Park lost its status as a private home. In the 1930s, it was converted to a hotel, in WW2 it was requisitioned for military purposes, and in the 1970s it was purchased by Gulf Shipping Lines with the aim of converting it to timeshare apartments and a leisure complex. It became the subject of a significant High Court judgement in 2018 to the effect that timeshare owners had rights to use the facilities (including tennis courts and a golf course) as easements, not just privileges. Though Kitchener would have turned in his grave to see his home put to such use, the mansion undeniably looks the classic golf clubhouse.

Camden Place

Camden Place

A house erected in Chislehurst in 1609 by the great antiquarian William Camden was replaced a century later with another called Camden House. Charles Pratt, the future Lord High Chancellor, bought it in 1760 and upgraded it to a Georgian mansion before adopting the title ‘Baron Camden, of Camden Place, in Chislehurst, Kent’. It came to national attention in 1813, when the owners Thomson and Anne Bonar were murdered by a servant; and again in 1871, when lawyer Nathaniel Strode – who had spent years extravagantly converting it to a chateau – offered it to the newly exiled Napoleon III, his wife, and their son. The house, complete with tricolour, consequently served as a French royal palace throughout the 1870s, during which both men died. After the dowager left in 1881, it was sold to builder William Willett, who constructed two 9-hole golf courses. These were taken over in 1899 by Chislehurst Golf Club, which consequently enjoys a unique clubhouse.

Capel Manor

Capel Manor

In 1859, John Francis Austin from Chevening, who owned Kippington House, engaged architect TH Wyatt to design an imposing house at Horsmonden. An Italianate construction, it bore the name Capel Manor. Austin contributed liberally to the design, which incorporated a huge hall, a mixture of styles, and many carvings. He died in 1893, leaving it to his much younger second wife Georgiana, who survived until 1931. It remained unoccupied until it was requisitioned in WW2 and used by various military units and the fire service. It inevitably suffered serious damage, and by 1966 had been demolished. In 1969, Tory MP John Howard sought to repurpose the winter gardens and arcade by building a compact modernist house there. Designed by future RIBA president Michael Manser, it resembled a fish-tank with an overhanging lid, although to be fair this may have been a provocative statement against classical architecture. In 2010, a second tank was added for guests.

Charlton House

Charlton House

Charlton House was a product of the spending spree that James I embarked on after the crown of England fell into his lap when he was 36. Not wanting his son Henry to be raised by Queen Anne, he constructed it as a home for the boy to be occupied jointly with his guardian, Adam Newton, who had come down from Scotland. Meanwhile, she resided at Placentia Palace in Greenwich, where she had two further children who both died young. Henry himself died of smallpox at 18, after which the House was surplus to requirements. It passed through several pairs of hands until, during WW1, the last owners made it available as a first-aid hospital, and after that sold it to London County Council. It was used as a hospital and a museum before becoming a public utility. It offers the additional benefit of the park adjacent to it, and boasts possibly the oldest mulberry tree in Britain.

Charlton Park

Charlton Park

Charlton Park, in the Elham Valley south of Bishopsbourne, was already inhabited by 1240, but the Tudor core of the current building was not erected until around 1580. In 1636, Sir Anthony Aucher bought it from the Gibbon family. It was presumably he, a Royalist imprisoned in the Tower during the Civil War, who built the new dower house connected to the main building by a 200-yard secret passage. In 1810, the house was given its Regency façade and a splendid first-floor ballroom where George IV courted his last mistress, Elizabeth Conyngham of Patrixbourne. Commandeered in WW2, it became a Barnardo’s home before reverting to private ownership. In 1970, the Medicine Ball Caravan festival was held in the grounds, featuring Pink Floyd, The Faces, and Mott the Hoople before just 1,500 spectators. Now down to its last 129 acres, the house is actively marketed as a picturesque wedding venue. It was on the market in 2021 at £3.5 million.

Chartwell

Chartwell

Chartwell House near Westerham would probably be unknown further afield but for the tenure of the man who won the BBC’s 2002 poll to decide the greatest Briton ever: Sir Winston Churchill. It has been described as representing “Victorian architecture at its least attractive” at the time he first saw it in 1921; but he immediately fell in love with the surroundings. After taking possession, he undertook expansive and expensive works that transformed it to its present look. He was to retain ownership for the rest of his long life. He spent little time there during WW2 because of the danger of an air-raid or commando attack, but returned either side of his second term as Prime Minister from 1951 to 1955. After his death in 1965, his widow gifted the house to the National Trust, which now makes it available for the public to view as it was between the World Wars.

Chevening House

Chevening House

The site of Chevening near Sevenoaks originally belonged to the estate of the Archbishop’s Palace at Otford. An earlier C12 construction was superseded in the 1620s by the current three-storey house, which is thought to have been designed by Inigo Jones. In 1717, it was considerably extended by the addition of two wings. It subsequently served as the seat of the Earls of Stanhope, a branch of the Earls of Chesterfield who then owned Boughton Place. The 7th and final Earl Stanhope wanted to leave a lasting memorial to his family, which for 250 years had distinguished itself in politics and science. When he died in 1967, a Board of Trustees took over the estate, charged with restoring and maintaining it as a residence for a person, nominated by the Prime Minister, who would pay their own expenses. It is currently shared by the two most recent Foreign Secretaries, Dominic Raab and Liz Truss.

Chiddingstone Castle

Chiddingstone Castle

Despite being sandwiched between two delights – Hever Castle and Penshurst Place – Chiddingstone Castle should not be overlooked. For nearly 400 years, the estate belonged to the Streatfeild family, who in 1679 converted the original timber-framed manor to a red-brick construction known as ‘High Street House’ because it sat on Chiddingstone‘s main thoroughfare. In the early C19, it was completely rebuilt as today’s Gothic castle, and the actual High Street was expediently removed from it. Lord Astor bought the estate in 1938, but it served as a Canadian military base in WW2 before becoming a school. It was finally bought in 1955 by the eccentric antiques collector Denys Bower, who in 1977 bequeathed it to the nation as a museum to house his intriguing collections, now under the management of the Denys Eyre Bower Bequest. No visit is complete without making the short walk to the lovely lily-covered lake.

Chilham Castle

Chilham Castle

The castle at Chilham guarding the road from Charing to Canterbury is actually two in one. The older, a distinctly Norman keep dating from 1174, is on the site of a possibly C7 Anglo-Saxon fortification. The scene of a spectacular reception for King Edward II in 1320 it is one of the oldest inhabited buildings in the country. A few yards away stands a crenellated manor house, a spectacular construction built as five sides of a hexagon. Built by 1616 for politician Sir Dudley Digges, it was long thought to have been designed by Inigo Jones, but this is now disputed. The Castle passed through a series of wealthy hands before being purchased by Indian real-estate developers Udit and Tishya Amin in 2022. Enjoying splendid gardens and beautiful views across the Stour valley, it is a popular choice for occasional tours and garden open days, not to mention film and TV productions.

Chilston Park

Chilston Park

Chilston is one of those country houses that were spared the fate of conversion to flats by being converted to a hotel. The redbrick house, which has been evolving since the C15, has too much other construction around it to look a gem; but that’s not to say it lacks merit. It boasts a pleasingly extended approach through its 190-acre country estate, a pair of attractive lakes, and a peaceful atmosphere for afternoon tea. The interior is also appealing, with a stairwell richly embellished with paintings, and decor that retains an authentic feel. The house has a long albeit uneventful history. There was a habitation on the site early in the C12, and the estate was subsequently owned by several families with political connections, including the Douglases from Scotland. James Douglas MP passed it on in 1875 to a new laird, Aretas Akers, who would become Home Secretary and then Viscount Chilston. A descendant disposed of it in 1983.

Chipstead Place

Chipstead Place

Originally the demesne of the de Chepsteads, Chipstead Place north-west of Sevenoaks belonged in the C16 to Thomas Cranmer’s son Robert. After being owned by C17 Sheriff of Kent David Polhill, it was acquired by William Emerton, who in the early C18 built a splendid new house containing 26 bedrooms and six reception rooms in 23 acres. After reverting to the Polhills, it changed hands again in 1829, and in 1862 was rented to railway pioneer Samuel Morton Peto. As so often, it was war that precipitated rapid decline, specifically when it was made available as a hospital for Belgian soldiers during WW1. Its contents having been sold in 1931, it was demolished to make room for a leafy housing estate; a local newspaper rued the loss of this latest “sacrifice on the altar of development”. Only isolated parts of the buildings survive, though the estate still accommodates the Chipstead Place Lawn Tennis Club established in the 1930s.

Cobham Hall

Cobham Hall

The first manor house at Cobham, west of Rochester, was built in the C12. In the Tudor era, the 10th Baron Cobham had the basis of the current building constructed, although a new centre block linking the two wings was added in the 1660s. The lords of Cobham Manor often held high office in Kent, including Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. Set in its 150-acre estate, the house was occupied by the Dukes of Richmond and Lennox from 1624 to 1672, and then by numerous generations of the Earls of Darnley, who made further enhancements to the house in the C18. The 10th Earl was obliged to sell the estate in 1959 on account of a heavy bill for inheritance tax. Since 1962 the house has been home to the Cobham Hall private boarding-school for girls, nearly half of whose pupils come from overseas. The house’s delightful two-storey Gilt Hall is also rented out for weddings.

Combe Bank

Combe Bank

In the C18, Colonel John Campbell built Combe Bank, a Palladian house in 518 acres at Sundridge. It came to national attention when his wife died bizarrely there. They had married in 1769 after her first husband, whom she had divorced for cruelty, was hanged for murdering a servant. Blaming their marriage, he wished an even worse death on her. In 1807, she was found incinerated in her chair, with only one thumb remaining, but little damage outside the room; the case gave rise to speculation about the paranormal existence of spontaneous combustion. The house was subsequently occupied by the mathematician William Spottiswoode, President of the Royal Society, who conducted experiments in electricity there and attracted such famous visitors as Charles Darwin and Oscar Wilde. Before WW2, the house was converted to a convent and school, and after serving as a hospital in WW2 was restarted as a school. In 2016, it was renamed Radnor House Sevenoaks.

Cooling Castle

Cooling Castle

Were it not for a devastating French raid on the Thames during the Hundred Years’ War, Cooling Castle would not exist. John de Cobham of Cobham Manor applied for royal permission to fortify a manor then by the riverbank on the Hoo Peninsula. It was granted in 1380, whereupon today’s irregular layout and iconic gatehouse emerged. The Castle saw no action before or after the revolt of 1554, when Sir Thomas Wyatt strangely took time out on his way to London to seize the castle. Even with an army of 4,000 that had just won a battle at Strood, it took eight hours to seize it against just eight defenders, which suggests de Cobham had done a good job. Unfortunately, Wyatt used cannon to breach its defences, leaving it uninhabitable. A century later, a farmhouse was built on the site, which today appropriately enough is home to super-cool pianist Jools Holland. Its barn is available for wedding hire.

Court Lodge

Court Lodge

The Norman owner of Leeds Castle, Robert de Crevecoeur, created a manor at Lamberhurst in 1166 that he conferred upon his nephew, who built a house there called the ‘Halle’. In order to avoid feudal service, he conveyed it to the abbot of Robertsbridge, who rented it back to him. With the Dissolution of the Monasteries, it was sequestrated by Henry VIII, and later gifted to Philip Sidney. Since being sold to William Morland in 1733, it has remained in that family, which rebuilt and enlarged it. In 1803, Jane Austen‘s cousin Thomas married Margaretta Morland, who may have suggested Catherine Morland, the heroine of ‘Northanger Abbey’, which was completed that year. The house was sequestrated by the Army in both World Wars, but recent owners have restored it, especially its impressive gardens. The golf course, which opened as Lamberhurst Golf Club in 1890, was popular with Siegfried Sassoon and later Denis Thatcher, who stayed there with his wife.

Danson Park

Danson Park

Just south-east of Welling is Danson Park, once a prestigious private estate but now a council-owned public utility. The estate was developed in the early C18 by John Styleman, a director of the East India Company. He left half to charity in 1734; but Sir John Boyd, another East India executive, re-unified it by Act of Parliament, and built the current house in 1768. Following personal and professional disasters, he became a recluse there until his death in 1800, after which his son sold the estate. It remained in private hands until 1924, when Bexley UDC bought it. Although the estate is now bisected by a road, and the house has become a registry office, the 190-acre grounds are still a joy to behold, embracing the historic Charter Tree and a charming Boating Pool. What’s more, there are various sporting amenities, the former stables survive as a pub, and local volunteers have beautifully restored the Old English Garden.

Davington Priory

Davington Priory

In 1153, a Benedictine nunnery was built in the countryside north-west of Faversham. It lasted for centuries until the last one of the nuns died in 1535. For the building itself, her demise was a godsend, because it was thereby spared destruction in the Dissolution of the Monasteries shortly afterwards. The Priory was sold by the Crown to the acquisitive Sir Thomas Cheney as a residence. Consequently, the parish church attached unusually remained in private hands until it was acquired by the Church of England in 1931, in the meantime losing one of its twin towers and being partially plundered for stone. The stained-glass window-maker Thomas Willement, who bought it in 1845, installed a ‘Thynke and Thank’ heraldic window that survives. In 1972, the Church sold the Priory house to style guru Christopher Gibbs, whose friend David Litvinoff, the shadowy socialite, was living there when he killed himself in 1975. Gibbs sold it in 1982 to the present owner, Bob Geldof.

Denne Hill

Denne Hill

The distinguished Denne family from East Kent could trace its ancestry back to before the Conquest, Robert de Dene having been a Norman steward to Edward the Confessor. One of his eminent descendants was the legislator Sir Alured (1185-1256). In one of the ‘Ingoldsby Legends’, Reverend Richard Barham (1788-1845) created a character with the same name, Sir Alured Denne, which scanned as felicitously as Betjeman’s “Miss J Hunter Dunn”. The poem relates how, after falling foul of St Romwold’s divine justice in the late C13, Sir Alured built Denne Hill, where his family still lived; or so Barham supposed. In reality, by the time he was writing in the 1830-40s, the Dennes resided at Grove Hill in Chislet, while Denne Hill was a prestigious Georgian house at Womenswold occupied by Lady Montresor. It was replaced in 1871 by a 16-bedroom affair in C17 Dutch style that still survives, and in the 1980s even housed Nicholas Treadwell’s ‘superhumanist’ art gallery.

Dent de Lion

Dent de Lion

One of William the Conqueror’s companions in 1066 was Aybeuare (Aubrey), an ancestor of the Dent de Lion family, whose name meant simply Lion’s Tooth. They gave their name to an estate west of Garlinge whose manor they fortified in 1440 in the face of an expected invasion on the coast half a mile away. Two centuries later, the estate was sold by the Pettits to Sir Henry Fox, the notorious Lord Holland who also owned Quex House and Kingsgate Castle, and transferred to his son, the controversial politician Charles James Fox. Later associated with smuggling operations, in 1820 the estate became the site of well-attended annual horserace meetings for over two decades, the name having morphed into Dandelion. The manor burned down in 1888, however, leaving only the extraordinarily well-preserved gatehouse, with four corner towers containing internal staircases. Though protected, the gatehouse has been engulfed by Margate’s unrelenting expansion, and now looks strangely out of time and place.

Denton Court

Denton Court

The manor of Denton, seven miles north-west of Dover, was recorded in the Domesday Book, but the first house there of which anything much is known was built in 1574 by Queenborough MP William Boys. It was sold to Samuel Egerton Brydges, the Wootton-born publisher of Lee Priory fame, who constructed a massive new house incorporating parts of the old building and moved there in 1792. Following a fire, a new owner, William Willats, substantially extended it, establishing a new south-facing façade. The imposing house with its 17 bedrooms, billiard room, and ballroom recently came on the market at nearly £3 million, which along with its 26 acres and two cottages sounded a snip until it became evident that major restoration was required on the scale of that at nearby Bridge Place, now a boutique hotel. Handily located next to St Mary Magdalene Church on the Canterbury Road just south of Denton, Denton Court’s future remains uncertain.

Doddington Place

Doddington Place

With its proximity to Sharsted Court and Belmont, Doddington Place is part of a historical Millionaire’s Row on the North Downs towards Faversham. There is not a great deal to be said about the house’s history, it being too recent to have had much happen there. It was built on the Doddington estate around 1870 by Sir John Croft, a member of the famous port-producing family, who until then had lived in a house called Whitemans a short walk away to the south west. The new house, standing in the middle of a classic 850-acre country estate, was designed to be an imposing red-brick and tile affair with gothic overtones. The property was sold in 1906 to General Douglas Jeffreys, and so passed by inheritance to the Oldfields, who retain ownership today. It was Mrs Jeffreys who gave the house its crowning glory, its impressive formal gardens, which are accessible to the public in the summer.

Douce’s Manor

Douce’s Manor

Either side of the road south out of West Malling lies the former estate of the Douce family. To the east lies the lake formed by widening the Ewell Stream, surrounded by grounds sold to Kent County Council in 1973 that now make up most of the 52-acre Manor Park Country Park. In the eight remaining acres to the west stands the house itself, built in 1776 for Thomas Douce. It was sold in 1803 to the Savages, served as a military R&R centre during WW1, and was converted to a ladies’ convalescent home. During WW2, it provided living quarters for RAF personnel serving at the nearby West Malling airfield. They converted the basement to a mess – known as the ‘Twitch Inn’ because of the aircrews’ understandable tics – that was frequented by such famous pilots as Guy Gibson and Roland Stanford Tuck. The house was left ruined, but later restored as a hotel-cum-restaurant and then Commercial Union’s conference centre.

Down House

Down House

Like Chartwell, Down House owes its fame to one previous occupant: England’s most famous scientist bar Newton, namely Charles Darwin. After his marriage to Emma Wedgwood, the great evolutionist needed somewhere to live that would offer a balance of rural tranquillity and nearness to London, then the scientific capital of the world. He alighted on Downe, a country parish north-west of Sevenoaks. A farmhouse existed at the site of Down House in the C17, but it was rebuilt and expanded around 1780. The Darwins weren’t sure when they first viewed it in 1842, but Emma finally fell in love with the views, while Charles liked the number of rooms, the local walks, and the price. After making many alterations, they settled there for the rest of their lives. Visitors relish seeing the ‘sandwalk’ where Darwin did his thinking, the greenhouse where he did his experiments, and the study where he wrote the earth-shattering ‘Origin of Species’.

Dukes Place

Dukes Place

In West Peckham, midway between Maidstone and Sevenoaks, there stands a scheduled monument that is as picturesque as it is historical. In 1405, Sir John Culpeper of Oxon Hoath, a knight at the court of King Henry V, had a large L-shaped house built there. A gift to the Knights Hospitaller, it was known as a ‘preceptory’, where returning pilgrims were treated to hospitality, and funds were raised to pay for crusades. The Hospitallers held as many as 76 such preceptories in England, but Dukes Place is today a particularly well preserved example. The north range, which burnt down in the C15, was rebuilt around 1500. After reverting to the Crown upon the Dissolution of the Monasteries, it was converted into labourers’ cottages in the C18, and fell into disrepair; but it has been painstakingly restored since WW2. Set in five acres and sporting a magnificent Great Hall, it is now a luxurious though expensive family home.

Eastgate House

Eastgate House

It is no surprise that Eastgate House took the fancy of Charles Dickens, being in his home town of Rochester and possessing a suitably exotic aspect. It was built by mayor Sir Peter Buck late in the C16, and passed through five generations of descendants. In the late C18 it became a school. It reverted to being a grand private residence in the 1870s, when a coal merchant bought it; but since 1890 it has been put only to public use. It has successively been a hostel for young men, a temperance restaurant, a library and museum celebrating Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, and a Dickens museum from 1923 to 2004. Thanks to a lottery grant, it was re-opened in 2017 as an exhibition centre. Dickens used Eastgate as a model for his Westgate in ‘The Pickwick Papers’ (1836), and the chalet in which he wrote several novels at Gads Hill now stands in Eastgate’s garden.

Eastry Court

Eastry Court

Located in Sandwich, Eastry Court must be the oldest house you will ever see appearing in estate agents’ listings – although claims that it is over 1,400 years old need to be taken with a pinch of salt. It is indeed the site of an early-C7 royal palace belonging to King Aethelberht I and his wife Bertha. Legend has it that their great-grandson, Ecgberht, had his two young cousins murdered in order to secure his line’s succession, and gifted the palace to the priory of Christchurch as a penance. When Becket fled from Henry II in 1164 on his way to Flanders, he hid at Eastry Court; and Edward III entertained his generals there on his way to invade France in 1341. Only traces of that edifice remain, however, the house having benefitted from major C14, C16, and C18 improvements. It declined again thereafter, but has been restored since the 1980s and now provides nine-bedroom luxury to its private owners.

East Sutton Park

East Sutton Park

One can only speculate what would have become of East Sutton Park if a German shell had not detonated next to 37-year old Captain Sir Robert Filmer MC in WW1. It made him the last of a line of ten Baronets of East Sutton, Kent who had occupied their country pile for three centuries. The first baronet’s father was Sir Robert Filmer, author of the controversial ‘Patriarcha’, whose own father acquired the estate around 1616. The original H-shaped house, built ca 1570, was subsequently expanded with another wing attached to its north-west corner; further modifications followed in the C19. The house was sequestrated during WW2, and in 1946 converted to a Borstal. Today it remains in the charge of Her Majesty’s Prison Service, accommodating around 100 adult women and young offenders. The Filmers must have turned in their graves when, in 2003, the prison was officially criticised for being insufficiently respectful of inmates’ wishes.

Eastwell Manor

Eastwell Manor

Eastwell Park is a large scenic area west of the Faversham Road out of Ashford, comprising parkland, agriculture, pasture, and a lily-covered lake. Sir Thomas Moyle had a manor house built there in the 1540s, which was replaced in the late C18 by the current building in mock Elizabethan style; a Tudor-style wing was added later. The grand gatehouse on Sandyhurst Lane, added in 1848 and known locally as Eastwell Towers, is worth seeing in its own right. After passing through the hands of two owners who went broke, Eastwell was occupied until 1893 by Prince Alfred, whose mother Queen Victoria visited regularly. His brother the Prince of Wales also came, and the future Queen of Roumania was born there. All changed after WW1. As often happened with unwanted old buildings, a serious fire broke out. The house was fortunately restored to its current state, and now operates as a hotel, complete with Champneys spa, smart restaurant, and golf-course.

Edenbridge House

Edenbridge House

Driving north up Main Road out of Edenbridge takes one past the inconspicuous entrance of what could be just another smart suburban home. The clue however lies in the discreet nameplate: Edenbridge House. What lies behind the façade is a vast rambling manor in the best English country tradition, complete with picture-book gardens and even an oast. The land was originally part of the vast Hever estate, the site long being known as Lyndhurst. Until the C20, it was a tenanted farm that changed hands many times. It was not until 1934 that the house was sold separately from the farmland, retaining around 15 acres of garden. Harold Mosenthal, a South African city trader, created the current zoned garden layout; while a new owner in 1953, Rio Tinto chairman Sir Val Duncan, renamed the property Edenbridge House, adding a water garden and swimming pool. Both kept a visitors book that contains famous names. The house is still a private residence.

Egerton House

Egerton House

The house at the top of Star and Garter Hill, west of Egerton, was originally a medieval timber-framed building, but now has a distinctly Georgian look. Once called Goodale, it was owned by John Dering of Surrenden in Pluckley. Generations later, it passed by marriage to the Husseys of Scotney Castle and then, in the C18, to Galfridus Mann of Boughton Place in Boughton Malherbe. In 1765, his son Horatio Mann is said to have entertained the Mozart family at the house during their week-long stay at his main residence, Bourne Park near Canterbury. A decade afterwards, Mann added a series of large reception rooms to the front of the house, with a scenic view down into the Weald. These came in handy two centuries later, the house having passed into the hands of the musical Gipps family in 1952. During the biennial Egerton Music Festival, the house and gardens regularly played host to well attended classical concerts.

Eltham Palace

Eltham Palace

The former royal residence opposite Royal Blackheath Golf Club is as rich in history as any in the county. Built around 1300, it was given to Edward II and used by English monarchs for two centuries. It was here that Henry IV entertained Emperor Manuel Palaeologos with jousting in the Palace’s own tiltyard. The Great Hall, built by Henry IV, was the scene of a historic encounter when fate threw together Erasmus, Sir Thomas More, and the future Henry VIII. Despite its three deer-parks for hunting, the Palace fell out of royal favour when Greenwich Palace was rebuilt around 1500. Van Dyck was permitted to live there, but the estate fell into ruination after the Civil War. In 1933, a lease was purchased by a member of the Courtauld textiles family, who built a new house around the Great Hall, decorated in Art Deco style and surrounded by beautiful gardens. The property is now managed by English Heritage.

Emmetts

Emmetts

Emmetts, at Ide Hill near Sevenoaks, is one of those rare properties that qualify as hidden gems. The name itself is a curiosity, coming from the Anglo-Saxon word for ‘ants’. The estate was so named because of the presence of numerous large anthills in the area. One reason why this appealed to Frederic Lubbock, who in 1890 purchased the house built there 30 years earlier, was that his brother was the renowned myrmecologist Sir John Lubbock from High Elms. Anthills are less in evidence today than blooms, the compact country house being enveloped by glorious flowerbeds that include an impressive rose garden directly in front of the house. The property was bequeathed in 1964 to the National Trust, which has not only spent some years restoring the gardens to their former glory but also laid on extensive walks through the adjacent parkland and woodland, affording impressive views from their elevated position above the Weald.

Fairlawne

Fairlawne

Fairlawne is a thousand-acre estate just north of Shipbourne and due east of Ightham Mote. The large house of that name was built for Sir Henry Vane the Elder, who like his son of the same name was a significant figure in the Civil War. The estate was acquired in 1880 by Edward Cazalet, a Brighton-born industrialist, who on arrival generously built a pub for the village, as well as a church where several Cazalets are now interred. One of his grandsons born at Fairlawne was Peter Cazalet, who famously trained racehorses there for the Queen Mother. In 1979, after Cazalet’s death, Fairlawne was sold to Saudi Prince Khalid Abdullah, a top racehorse owner. Fairlawne became the focus of a legal dispute in 2011, when Kent County Council permitted the Prince to close off an ancient footpath crossing the estate; the decision was reversed on the instructions of the Planning Inspectorate, following protests by villagers.

Finchcocks

Finchcocks

A family called the Finchcocks is said to have lived on the site in Goudhurst as early as the C13. The current distinctly Georgian house was built in 1725. The main structure could be a classic town-house, but for the 13-acre gardens surrounding it. The façade is ingeniously designed, the four storeys of decreasing height lending the house an impression of stretching up into the sky. The house is only 40 feet deep; its rooms are interconnecting, with no corridors, after the manner of a Wealden hall-house. The oak-panelling and high ceilings on the ground floor lend themselves to musical performance, for which reason the new owners in 1970, the Burnetts, built a superlative collection of musical instruments there. It was made accessible to the public as the Finchcocks Musical Museum until 2015, when the Burnetts retired and much of the collection was sold off. The current owners, the Nichols, run residential piano courses at the house.

Foots Cray Place

Foots Cray Place

Palladio’s Villa La Rotunda, built in the late C16 near Vicenza, was a masterpiece of neoclassical design, and inevitably inspired imitations. Four copies were built in England, of which two – Mereworth Castle and Chiswick House – still stand. One that did not survive was Foots Cray Place. It was built on the site of a medieval manor house near Sidcup that until 1676 had remained in the hands of the Walsinghams, including the notorious spymaster Sir Francis, for six generations. London pewterer Bourchier Cleeve purchased the estate in 1752 and within two years had the Palladian house built. Its external beauty was matched by the opulent art collection he housed inside. The house subsequently passed through numerous hands before being requisitioned as a naval training college during WW2, and wrecked. It was sold to Kent County Council as a museum, but expediently caught fire in 1949 and was demolished. The 220-acre grounds are now a public park.

Ford Palace

Ford Palace

The old Archbishop’s palace at Hoath, nearly seven miles north-east of Canterbury and close to Herne Bay, was one of fifteen outside of Canterbury. The ‘Ford’ in the name referred to the point where the Roman road from Canterbury to Reculver crossed a stream. It has been speculated that there was an archiepiscopal residence here in Anglo-Saxon times, but no certain record exists before the C14. It was impressively rebuilt in the late C15, with a tall tower added. Archbishop Cranmer was a fan of the place: he hosted Henry VIII there in 1544, and was in residence nine years later when he was fatefully summonsed to appear before the Privy Council. Most of the Palace was destroyed by order of Parliament in 1658, after which its chapel was used as a barn until that too was demolished in 1964. The old gatehouse now forms part of the listed Ford Manor Farmhouse, which also includes a C15 wing behind a C18 red-brick façade.

Foxbury Manor

Foxbury Manor

In June 2009, on the eve of a sell-out concert season in London, pop superstar Michael Jackson was ready to move into Foxbury Manor. Situated close to London next to Chislehurst Caves, but resembling a romantic château, it appealed enough to justify spending a million pounds on rent for a year. Rooms in the £15 million house had been themed for Wacko Jacko’s children, and the 8-acre gardens, surrounded by an 8-feet high security fence, had been made over to include fairground rides and a bowling alley. The owner, care-homes entrepreneur Osman Ertosun, had already moved his family out when Jackson’s physician fatefully administered an overdose of propofol. The controversial star’s death ignited fans’ unbridled grief, but also the relief of local residents familiar with the ways of paparazzi. Ironically the house, built in 1875, had been a retreat for bishops’ and missionaries’ families in the 1940s, well before the 32 bedrooms were cut down to 11 luxury suites.

Franks Hall

Franks Hall

In 1220, a manor house was built at Horton Kirby, on the east bank of the Darent north-east of Farningham, by the Frankish family. Three centuries later, it was inherited by Lancelot Bathurst, who built a new house on the opposite bank in 1591. It was impressive: a three-storey red-brick cube of pure Elizabethan grandeur. The house passed on through generations of Bathursts until the mid-C18. After being inherited by a Yorkshirewoman who took no interest, the estate was sold in the 1850s to a farmer, who used the house as a barn. After his death, it was sold, rebuilt, sold, re-sold, and finally in 1910 sold back to Lord Bathurst, 153 years after his family lost possession. Sadly, it didn’t stay long: he gifted it to his son, who left it empty. Apparently unloved, it has since passed through various other hands. Four-fifths of its 446 acres have now been sold off, though a Tudor garden remains.

Fredville House

Fredville House

Unlike its namesake in Kentucky, the Fredville estate at Nonington was not named after an individual. Hasted, a fine antiquarian but no linguist, thought its name derived from the French for ‘cold’, and so described the local microclimate, whereas it was much more likely a corruption of the Germanic word ‘frith’ meaning a patchy wood and ‘vill’ signifying an administrative unit. Originally owned by Dover Castle, it was purchased by John Colkin in the C14, and subsequently owned by the Boys, Brydges, and Plumptre families. While occupied by the Canadian army in 1940, the house was gutted by a blaze, largely because the six fire brigades who attended were unable to muster much water in that remote location, and a fire initially confined to one room spread uncontrollably. Fredville is now best known as the site of the Fredville or Majesty Oak, one of particular antiquity and size among its many splendid specimens.

Frognal House

Frognal House

In 1253, King Henry III granted the right to kill game in an area a mile east of Chislehurst. Within 300 years, the Dynley family had built a manor there. It was sold early in the C17 to William Watkins, who demolished all but a staircase and an arch and replaced the stone building with a two-storey Jacobean brick edifice. Concerned that it would be confiscated by Parliament, he sold it to the respectable Warwicks. They bequeathed it to the nouveaux riches Tryons, who around 1700 connected the mansion up with outbuildings and formal gardens. It was bought in 1752 by Thomas Townshend, father of the 1st Viscount Sydney, and remained in the family until 1915, when it was sold to the Government to form the Queen’s Hospital. A new Queen Mary’s Hospital was built in its place in 1974, which 25 years later became the first Sunrise care home. Whatever Frognal House may offer, continuity isn’t it.

Gads Hill Place

Gads Hill Place

Architecturally speaking, there is nothing special about Gads Hill Place in Higham, a smart but simple house built in 1790 for an ex-mayor of Rochester; but there is a special story attached to it. In 1821, aged nine, Charles Dickens considered it the epitome of a rich man’s abode. After his father told him that, if he applied himself, it might one day be his, Dickens used to walk there from Chatham to remind himself. Three years later, Dickens Senior was thrown into Marshalsea Debtors’ Prison for living beyond his means, while Dickens Junior went on to make a fortune writing books about poverty. He earned enough to realise his childhood dream by buying Gads Hill Place in 1856. He was visited there by numerous creative personages, one of whom, the actor Charles Fechter, gave him the large two-floor Swiss chalet in which he wrote his last four novels. The house is now home to an independent school.

Glassenbury Park House

Glassenbury Park House

Halfway between Goudhurst and Cranbrook, Glassenbury was originally ‘Glastenbury’. The eponymous park’s story dates back to the C12, when the Tilleys owned it. In 1377, Joanne Tilley married Stephen Rockhurst, who in 1399 built a stone mansion on Winchet Hill. In the C15, Walter Rockhurst, who perhaps had something to fear, both altered his name to Roberts and built a new house on an earthen platform in the marsh below the hill, creating the moated construction that survives today. The house was substantially renovated after a fire in 1726, and in 1778 mistakenly bequeathed to unrelated Irish Robertses who let it fall into disrepair. Considerably altered in the 1870s and 1950s, the house was sold off in the 1970s, and remains in private ownership. The estate boasts woodlands, restored after being badly damaged in the 1987 storm; a lime avenue; and a pedestal marking the grave of Napoleon’s horse Jaffa, which lived there after Waterloo.

Godinton House

Godinton House

In the hands of a not-for-profit trust since 1995, Godinton House provides an unusually digestible stately-home experience. North-west of Ashford, it consists of a medieval hall that had a gabled Jacobean brick mansion built around it. The beauty of Godinton is that it remained in the hands of the Toke family for nearly five centuries. Its character therefore never changed much, even after it was sold to George Dodd in 1895 and Mrs Bruce Ward in 1919. A guided tour has the virtue of giving a real flavour of what it was like to live there, but without trying the visitor’s stamina. The one feature that differs greatly from the Tokes’ days is the various gardens, including an impressive lily pool, that were designed in the late C19 by architect Sir Reginald Blomfield. Spectacular in their own right in summer, they are bounded by the massive sculpted yew-hedge that is Godinton’s hallmark.

Godmersham Park

Godmersham Park

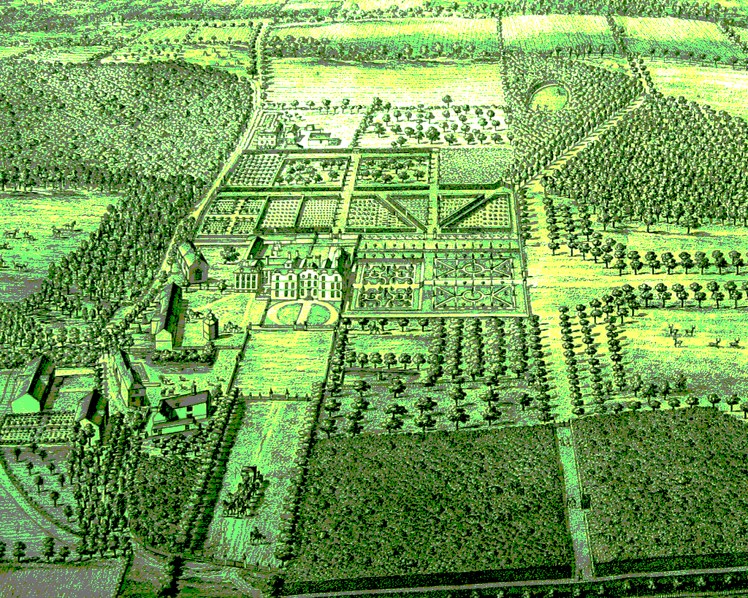

Godmersham is famous as the likely inspiration for Jane Austen’s ‘Mansfield Park’. In Elizabethan times, the Brodnax family had owned Ford House on the Ashford-Canterbury road. Thomas Brodnax MP, who by then had changed his name to May, replaced it in 1732 with the current main building. Ten years later, now renamed Knight, he enclosed it in the 600-acre Ford Park, and added the house’s wings in 1780. It was inherited in 1794 by a family cousin, Edward Austen, who later also changed his name to Knight. Between 1798 and 1813, he was frequently visited by his famous sister, Jane. Now called Godmersham Park, it was reworked after 1852 by Knight’s son Edward. A more major overhaul took place in 1935 when, after decaying during three changes of ownership, both house and gardens were substantively restored by the Trittons. Godmersham was eventually acquired by Sunley Farms, who since 2001 have rented it out as a training college for opticians.

Goodnestone House

Goodnestone House

Named after previous lord of the manor Godwin, Earl of Wessex, Goodnestone originally sported a Tudor house owned by Sir Thomas Engeham. After being abandoned, it was purchased in 1705 by barrister Brook Bridges, demolished, and replaced by the current Palladian house, which soon had extensive formal gardens added. However, Bridges’ great-grandson, the 3rd Baronet, replaced these with a fashionable landscape park in the late C18. His daughter Elizabeth married Edward Austen in 1791, the couple living on the estate at Rowling House. Like Godmersham – 11 miles away as the fit crow flies – the estate was consequently visited regularly by Austen’s sister, Jane, who began writing ‘Pride and Prejudice’ after one stay. The 5th Baronet added a portico in the 1840s, as well as terraced lawns. These evolved over time into today’s magnificent gardens, restored in the 1960s, which are open to the public in summer months and rated among the best in the country.

Gore Court

Gore Court

Otham’s Gore Court used to have 39 acres of magnificent gardens and parkland, but they have now mostly been obliterated and returned to arable use. Some relics remain, however, including a 300-year-old cedar and Southern England‘s biggest tulip tree. As recently as 1949, the house and gardens were still sufficiently impressive to provide the backdrop for a memorable scene in ‘Kind Hearts and Coronets’, when Louis D’Ascoyne Mazzini flirts with Edith D’Ascoyne over tea in the garden while her photographer husband Henry is heard blowing himself up in the distance. The estate originally belonged to Bishop Odo, but then passed through countless hands across the centuries, notably including the Hendleys from the C16 to around the 1790s. The house was built around 1500, but was substantially altered and added to in the late C16 and late C18. More recently, it has spent time as an aircraft factory, a nursing home, and a school, before reverting to a house.

The Grange

The Grange

Augustus Pugin, the high priest of neo-gothic architecture, decided in 1843 to remove himself from London to Ramsgate. Having converted some years earlier to Catholicism, he designed himself a large home with a spiritually sympathetic ambiance at one end of Royal Esplanade. At his own expense, he added the adjacent St Augustine’s church. The Grange is not the easiest to spot, being tucked away in what resembles a Norman enclave. It is most easily viewed from the churchyard, where the separation between gable and tower at either end makes the house unmistakable. The tower was not just for ornament: it gave Pugin somewhere to place a telescope with which to observe vessels at sea. Though the exterior of The Grange is more pleasing than exciting, the interior is strikingly opulent and ornate. The house was saved from redevelopment in 1997 by the Landmark Trust, which now makes it possible to arrange visits, or even book a room.

Great Maytham Hall

Great Maytham Hall

Though its name may be unfamiliar, Great Maytham Hall has a claim to literary fame. It was here that, during her nine-year stay, Frances Hodgson Burnett discovered a hidden garden that gave her an idea. The estate, near Rolvenden, had travelled a familiar path, from medieval manor to fashionable C18 construction, complete with broad gravel drive. The new building, completed in 1760 by the Monypennys, lasted only 133 years before suffering a serious fire. The two wings survived, however, and from 1909 Lutyens rebuilt the main house two floors higher than its predecessor. The £24,000 bill was footed by MP Jack Tennant, who’d chosen the site after hearing it had the least rainfall in Kent. Hodgson Burnett published ‘A Secret Garden’ even before the work was completed, having herself restored the garden as a haven to write in. After Tennant’s death, the house became a home for the blind, and fell into disrepair before being converted to flats.

Greenwich Castle

Greenwich Castle

The top of the hill in Greenwich Park was chosen in 1437 by the late Henry V’s brother Humphrey, the Duke of Gloucester, as the site for a folly – a small tower called Mirefleur. A century later, now significantly larger and possessing even a moat and gatehouse, it was known as Greenwich Castle. Henry VIII made use of it as a hunting lodge, while it doubled as somewhere to keep a mistress within easy walking distance of Placentia Palace. In 1605, Henry Howard, the Duke of Northumberland and Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, moved in and added a garden, among other improvements. Having been badly damaged by the Parliamentarian army, the site was transformed in 1675 for a quite different purpose. The castle was demolished, and Flamsteed House built for the first Astronomer Royal. It subsequently became much better known as the Royal Observatory, home to the Greenwich Meridian.

Groombridge Place

Groombridge Place

What is surprising about Groombridge Place is how little has happened there. The earliest record of a manor house is from 1239, when a small castle was built with a moat. Ownership then rattled through numerous aristocratic hands, including the de Cobhams, the de Clintons, and the Sackvilles. The current house was built in 1652 by barrister Philip Packer, with advice from his friend Christopher Wren. After his death, the deserted house may have become a haunt of the notorious smugglers the Groombridge Gang. Arthur Conan-Doyle used to think the house haunted. And that’s it. The real beauty of Groombridge is its beauty. The house, entirely surrounded by its water moat, looks the quintessential old English manor. Furthermore, the extensive gardens are a delight; the diarist John Evelyn, also a noted horticulturalist, assisted Packer with their design. Though the house is private, the grounds are open to the public, and include a discreetly distant ‘Enchanted Forest’ for youngsters.

Hadlow Castle

Hadlow Castle

Of all Kent’s lost treasures, Hadlow Castle is perhaps the most regrettable. It was an architectural masterpiece, built in the late C18 after the fashion of Horace Walpole’s neo-gothic castle, Strawberry Hill. Its visual impact was not unlike Happy Potter’s Hogwarts. Yet, after suffering the ill effects of military occupation during WW2, most of it was demolished in 1951. Some elements survived, including the Entrance Arch in the High Street and, most visibly, the 210-foot tower that still looms large over Hadlow. Known as May’s Folly after the Walter May who had it built, the Tower is the tallest folly in Britain. Having served as a watchtower in WW2, it was seriously damaged in the 1987 storm, and the 40-foot lantern at its summit was later removed. It is now in private hands. Although intriguing in its own right, its presence is almost painful as, Ozymandias-like, it reminds us of what’s been lost.

Halden Place

Halden Place

Lying a mile or so north of Rolvenden in the Weald, Halden Place was a house of historical significance, insofar as it is said to have been one of the many residences of Lady Jane Grey, the unfortunate Nine Days’ Queen. It got its name from its original owners, the de Halden family, who built it in the C14. It passed by marriage to the Guldefords, whose Sir John obtained permission from the new King Henry VII to fortify it with crenellations in 1487, even though he had previously been Edward IV’s Comptroller of the Household. It was evidently a grand affair, even having a moat. However, it is no longer to be seen. It was replaced in 1740 with today’s large farmhouse, complete with two oasts. The remains of the moat do survive, however, and the de Guildford arms, recognisable from the Christchurch Gate in Canterbury, can be seen on the C17 stable block.

Hales Place

Hales Place

The Hales baronets were movers and shakers in C17 politics. The first, known as Kent’s richest commoner, was a committed Royalist in an era of republican insurgency, and his grandson a commander in the Kentish revolt against Parliament in 1648. Although they had three large properties in Tunstall – one never completed – it was not enough. In 1675, the 3rd Baronet bought Place House, a property to the north of Canterbury. A century later, his descendants used its site to build a new home, a vast edifice truly worthy of the family name. Constructed in the late 1760s, Hales Place enjoyed a magnificent view down over the city. Eventually, however, the family ran out of money. The house was sold in 1880 to French Jesuits who turned it into a college. A half-century later, it was demolished. Hales Place is now a housing estate that, with supreme irony, is home to large numbers of Canterbury’s legendarily left-wing student population.

Hall Place

Hall Place

It is worth travelling to Bexley just to see the architectural equivalent of a griffin. The original Hall Place was splendid enough, built in 1537 for a rich merchant called Sir John Champneys with stone from a dissolved monastery. Constructed around an impressive Great Hall, the house’s outside walls featured an attractive checkerboard design. All was well until 1649, when another rich merchant, called Sir Robert Austen, wanted something twice as big, and tacked a red-brick building onto the end of the old stone one. He at least had the sense to make them the same height, though one wonders why his wife didn’t talk him out of it. It didn’t deter plenty of socialites from buying or renting the house thereafter, until the US Army interrupted the gaiety in WW2. After serving as a girls’ school and a municipal building, the chimera was turned into a tourist facility in 2005. Admission to its gloriously coherent gardens is free.

Hayes Place

Hayes Place

It may be little remembered now that it is gone, but Hayes Place in Bromley once figured in history. A house already stood there in the C15, but prime minister William Pitt the Elder, Lord Chatham, bought it in 1754 and built a new one, where his eminent son was born and he himself would die. The son, Pitt the Younger, moved in 1785 to Holwood House a mile further south, where he and Wilberforce embarked on ending slavery. About a century later, Hayes Place was acquired by Everard Hambro, the eminent banker, whose son Eric sold it for development in the 1920s. The house, once a focal point of democracy that had attracted many of the late C18’s major parliamentary figures, was demolished in 1933, and the estate replaced by acres of suburban housing. Nothing remains of its historic significance except some street names: Pittsmead Avenue, Chatham Avenue, Hambro Avenue.

Heronden Hall

Heronden Hall

Nobody heading west out of Tenterden can miss the grand gateway at the junction with Smallhythe Road. What lies beyond is the large estate that belonged to the Heronden family from the early C13 onwards. As it was broken up in the C17, there are now four large houses named ‘Heronden’. The foremost, built in 1585, became known as Heronden Hall. It was acquired in the 1630s by John Austen, Mayor of Tenterden and brother of the Sir Robert Austen who owned Hall Place in Bexley. Sir Robert’s son, also Robert, inherited Heronden Hall from his uncle; but, owing to a family rift, Robert’s grandson left the house to a cousin. It was pulled down in 1782, and in 1853 the current Heronden Hall, a curious Tudor Gothic affair, was built for one William Whelan. Among its more recent owners was the 10cc drummer and video director Kevin Godley, to whom that imposing gatehouse also belonged.

Hever Castle

Hever Castle

The home of Anne Boleyn is one of Kent’s truly unmissable visits. A crenellated C13 manor house, it is the quintessential English castle in having not just a moat, a maze, and magnificent gardens, but also a gruesome history. It was home to Baron Saye and Sele, the man who earned the particular displeasure of Jack Cade’s rebels in 1450 and was parted from his head. Two centuries later it was the turn of Thomas Boleyn, who evaded the axe himself but saw two offspring dispatched by Henry VIII. Expropriated as a royal residence, the Castle was next occupied by Anne of Cleves. Thereafter it decayed steadily until it was rescued by Lord Astor, America’s wealthiest man. Today, aside from welcoming wide-eyed visitors, the castle offers bed and breakfast. There is nothing so unforgettable as a stroll beside the timeless lake, followed by a night in a room where an apparition carrying her head on her arm would be no great surprise.

Higham Park

Higham Park

Higham Park takes its name from the de Heghams, to whom Edward II granted lands at Bridge in 1322. Two centuries later, it was bought by young Thomas Culpeper, Henry VIII’s friend who would be executed for his alleged dalliance with Queen Catherine Howard. So began the Park’s long association with the rich and famous. Among its many visitors are said to be Mozart, Jane Austen, and even French president de Gaulle. It got a new lease of life in 1901, when banker William Gay installed his exotic plant collection and built a huge water-garden incorporating England’s largest domestic canal. In 1910, the super-rich Countess Zborowski bought the estate for £17,500, leaving it to her 16-year-old son Louis when she died a year later. A motor-racing fan, he turned the stables into an engineering works; the cars that inspired Ian Fleming’s ‘Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang’ were built there. The house was ruined during WW2, but is now being restored.

High Elms

High Elms

So glorious is the 250-acre High Elms Country Park on the North Downs near Farnborough that Men of Kent might ask: why didn’t Kentishmen put up a fight before letting London pinch it? In the C11, the estate was granted to Bishop Odo, no doubt for hunting. It was purchased around 1800 by banker Sir John Lubbock, one of whose grandsons, Lord Avebury, was a personal friend of Charles Darwin on the other side of Downe village. Sold to Kent County Council in 1938, it became a training centre for nurses; and in 1967, just two years after falling under the aegis of London County Council, the Lubbocks’ magnificent mansion mysteriously burnt down. To be fair, London is doing a decent job of looking after its charge. Now a nature reserve, High Elms provides a delightful leisure facility, laying on a wealth of country terrain in addition to some formal gardens and an ecologically conscious visitor centre.

Hole Park

Hole Park

Rolvenden’s Hole Park is now best known for its splendid gardens; but the house at its centre has a track record. There was originally a Wealden farmhouse on the site, which had a new Queen Anne house added to the front in 1720. It was owned for generations by the Gibbon family, from whom Edward Gibbon – author of ‘The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire’ – claimed his descent. The farmhouse was demolished in 1832 by the MP for Rye, Thomas Gibbon Monypenny, who built a new house in Elizabethan style around the later edifice. Like so many large Kentish houses, it was taken over in WW2 for use as a barracks, and left in too bad condition for the owners, the Barhams, to move back into. Instead, the current owner’s father decided to strip it back to the 1720 construction and erect a new house suitable for modern living. Nowadays the 16-acre gardens draw 15,000 visitors a year.

Holland House

Holland House

In a glorious position overlooking Kingsgate Bay, Holland House was built around 1750 by Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland (1705-74), Britain’s thoroughly dissolute and corrupt Secretary of War, who named it after his London abode. Although now unremarkable of itself since its grand portico was removed, this Georgian house was just the pivot of Fox’s equivalent of a personal theme park. The building behind it, now the Port Regis care home, was intended as a convent, but instead became accommodation for visitors and staff. He later built Kingsgate Castle on the cliff-top as his stable block, and the Captain Digby inn in tribute to his seafaring son-in-law. Most curiously, however, he dotted extravagant follies all around the estate, including an arch to commemorate King Charles II’s chance landing during a storm in 1683. A later owner was John Lubbock, 1st Lord Avebury, who enlarged the Castle as his residence. Both House and Castle are now divided into apartments.

Hollingbourne Manor

Hollingbourne Manor