Penenden Heath, ca 1908

The arrival of the Romans (55 BC)

The arrival of the Romans (55 BC)

A new era began in August 55 BC, when Roman legions first set foot on British soil. Their commander Julius Caesar ostensibly aimed to punish the Britons for interfering in his Gallic campaign, but doubtless also had booty and glory in mind. The expedition was not conspicuously successful. Finding Dover Beach stoutly defended by Celtic spearmen, he decided to sail several miles north to an alternative landing-place. High winds had forced the transports bearing his cavalry to turn back, and it legendarily took the plucky example of the 10th Legion’s standard-bearer to encourage the 10,000 infantry to disembark. After stormy weather battered many of Caesar’s 600 ships, however, he felt obliged to withdraw. He learned his lesson. The following July, he returned with five legions and 2,000 cavalry, built a 50-acre fort, and wrought havoc in the South-East for two months. Though a plaque celebrates his landing-place at Walmer, recent archaeological discoveries suggest Pegwell Bay as the true location.

The flight of Amminus (~40)

The flight of Amminus (~40)

The first known ruler specifically of Kent was a Brython called Amminus. He was a son of Cunobelin, the Catuvellauni warlord who presided over most of South-East Britain during and beyond the time of Christ. As evidenced by coin finds, Amminus specifically ruled the Cantii. The Roman historian Suetonius reports that he was unseated around the year 40 and fled Britain. The reason is unknown: he may have rebelled unsuccessfully against his ageing father, or his brothers Caratacus and Togodumnus may have deposed him because of his Roman sympathies. He fled to the Rhine with his supporters and bowed there to the megalomaniac Roman emperor Caligula, who trumpeted this supposed triumph. ‘Adminus’ encouraged Caligula to invade Britain; but, though plans were made, the notoriously undependable imperator did not see them through. Nevertheless, the Romans’ refusal to extradite him may have exacerbated his brothers’ hostility to Rome, which was to provide a key pretext for Claudius’s full-scale invasion in 43.

The Battle of the Medway (43)

The Battle of the Medway (43)

The first battle on British soil recorded in history took place in Kent. Following the Roman invasion under Aulus Plautius, the native Britons under Caratacus and Togodumnus were beaten in two skirmishes in East Kent, and retreated to the Medway somewhere between Aylesford and Rochester. According to the historian Cassius Dio, who provided the only account of the battle, the pursuing Romans arrived to find them massed on the western bank, and a battle ensued. Unusually, it lasted two days, suggesting that it was hard fought. On the first, auxiliaries swam across the river to attack the British chariot horses while the main army crossed the river in the confusion. On the second, Hosidius Geta’s legion mounted a surprise attack. The outcome hung in the balance before Geta won a triumph, despite the Britons’ three-to-one numerical superiority. Around 5,000 Britons were killed, and 850 Romans. The Celts retreated to the Thames, but were only delaying the inevitable.

The Battle of Ebbsfleet (466)

The Battle of Ebbsfleet (466)

The Dark Ages are so called not because they were uneventful or miserable, but because they left us next to no contemporary records. Those accounts that exist were mostly written long after the event, are short on detail, and seldom tally. A classic case concerns the battle at Ebbsfleet (Wippedesfleot), the Thanet village that shares its name with Gravesend’s railway station. We can deduce that, in 449, Germanic warriors were invited in by a Brythonic overlord to assist in his war with the Scots. They eventually turned on him and sought to take possession of Kent. A war followed, with landmark battles probably at Aylesford (455) and Crayford (457). By 466, the invaders were driven back to the place where they’d first entered Britain, and possibly forced to flee. Yet, determined to have their prize, they must have returned with a bigger army that drove out the Brythons for good. Undeniably Ebbsfleet heralded the dawn of the 400-year Kingdom of Kent.

The foundation of the King’s School, Canterbury (597)

The foundation of the King’s School, Canterbury (597)

The King at the time when Kent’s premier school was founded was not the usual Edward, George or Henry; it was Aethelberht. The bewildering fact is that the King’s School was founded nearly a thousand years before both Eton and Harrow. Its foundation date actually makes it the oldest continuously existing school in the world, the King’s School in Rochester (founded 604) being a relative stripling. It was the brainchild of St Augustine, who initially got teaching underway at his new Abbey. It acquired its present name from King Henry VIII, who granted it a royal charter in 1541 after the Dissolution of the Monasteries. It started admitting girls in the 1970s, and became fully co-educational in 1990. King’s now can accommodate around 900 pupils in 16 houses, of which 13 are boarding-houses. Its most famous alumni are Christopher Marlowe and Sir William Harvey, although the one best known to today’s pupils is probably children’s author Sir Michael Morpurgo.

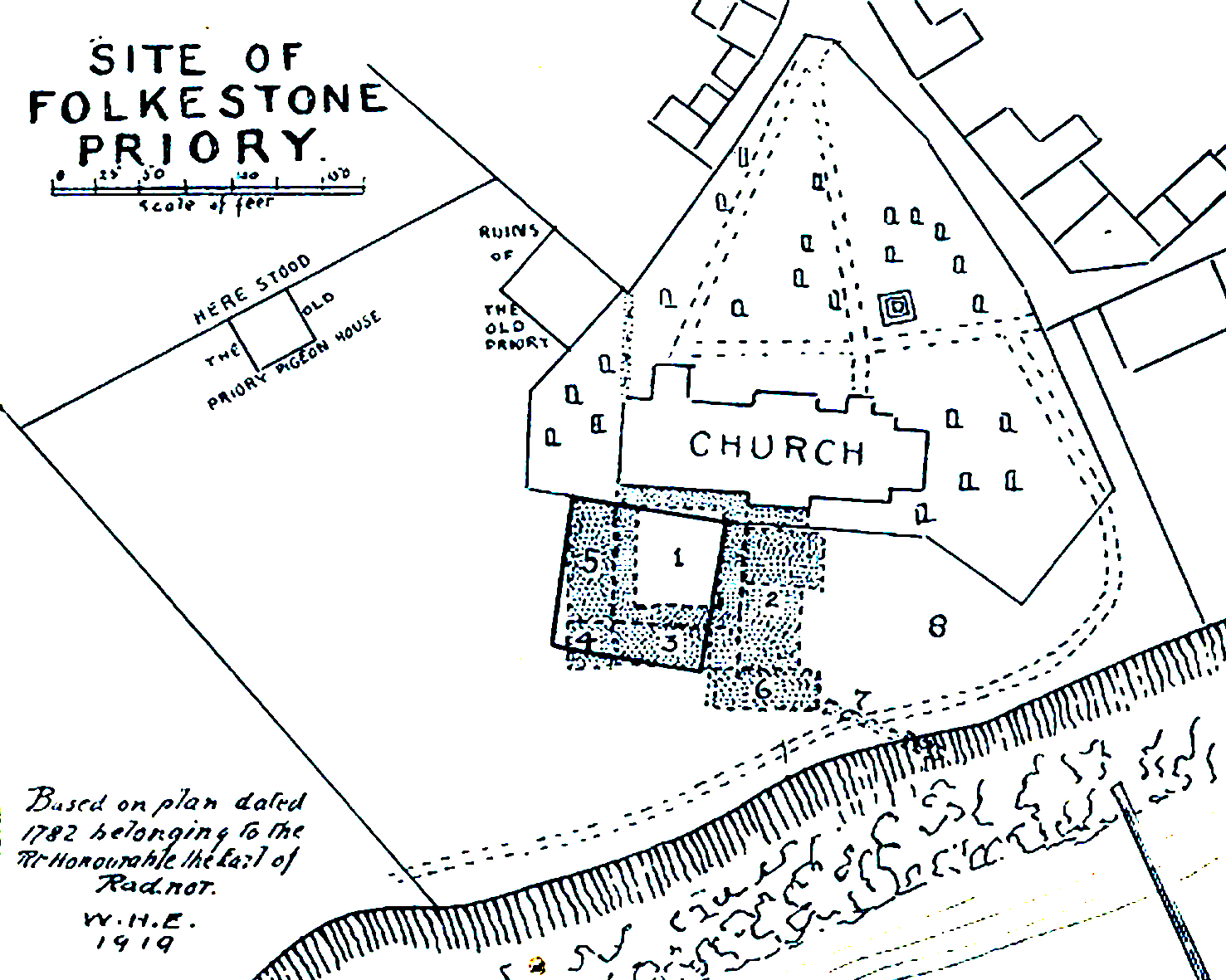

The foundation of Folkestone Abbey (ca 630)

The foundation of Folkestone Abbey (ca 630)

There is no point in looking up Folkestone Abbey on Tripadvisor: it ceased to exist many centuries ago. In its day, however, it was a significant institution, being the first ever nunnery to be established in England. Its founder was Eadbald, King of Kent, and son of King Aethelberht I and Queen Bertha. He had it built for his daughter Eanswith at the time of her birth around 630; she may have served as its abbess, for she was later canonised despite dying at around 20. Unfortunately, it was unable to withstand the depredations of Danish Vikings, and what remained of it eventually fell into the sea. In 1137, however, a monastery known as Folkestone Priory was built nearby. Eanswith’s bones were reburied within the walls of its chapel, which stood on the site of today’s St Mary and St Eanswythe’s Church. Interestingly, the bones of a young female discovered there in 1885 have now been dated to the C7.

The 1st Battle of Otford (776)

The 1st Battle of Otford (776)

After the Kingdom of Kent had enjoyed three centuries of affluence and relative stability, the peace was disturbed in the usual manner: by a megalomaniac bent on empowering and enriching himself. The change was occasioned by the death of King Aethelberht II in 762. Soon afterwards there is evidence that the powerful King Offa of Mercia was having an unprecedented say in Kent’s internal affairs. By 785, Offa was plainly the direct ruler of Kent, having subsumed it into his Mercian domain. In between, the ‘Anglo Saxon Chronicle’ gives us tantalising evidence of a battle at Otford in which the Kentishmen took on their mighty opponent. The record does not say who won, but the fact that King Egbert issued his own charters afterwards suggests a temporary reverse for the master. The following year, however, he won an important victory over his main rival, Wessex, and was again able to turn the screw on Kent. Independence would not be restored until his death in 796.

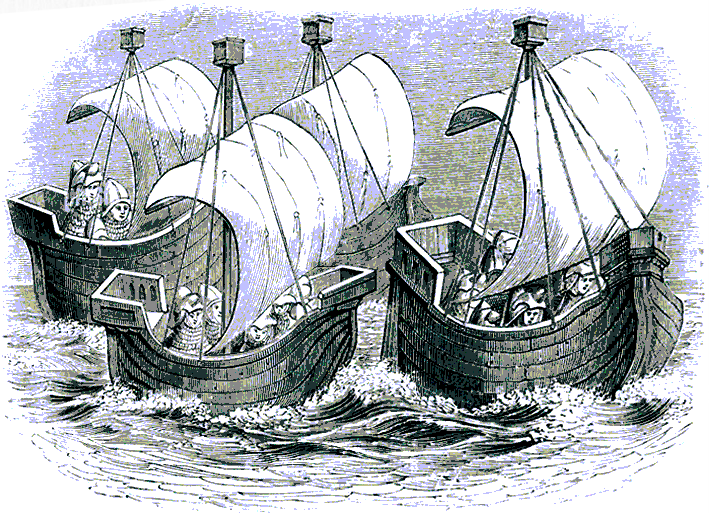

The 1st Battle of Sandwich (851)

The 1st Battle of Sandwich (851)

By the middle of the C9, the threat from the East presented by red-bearded men in longboats was serious, and incessant. They didn’t always get their own way, however. In 851, King Aethelstan of Kent took on a large Viking fleet off Sandwich. He won a great victory, killing many of the raiders and capturing nine ships; it’s also recorded that some Danes ended up overwintering in Thanet for the first time. The battle has been labelled the first recorded sea battle in British history. It was doubly auspicious that the locals should have won it. For Kent, it was fine achievement for a county that would go on to be a mainstay of naval enterprise. For Britain, it was a classic victory over a world-class opponent for a nation that, a thousand years later, would possess the finest fleet in the world. Unfortunately, it would provide only short-term respite against an implacable foe.

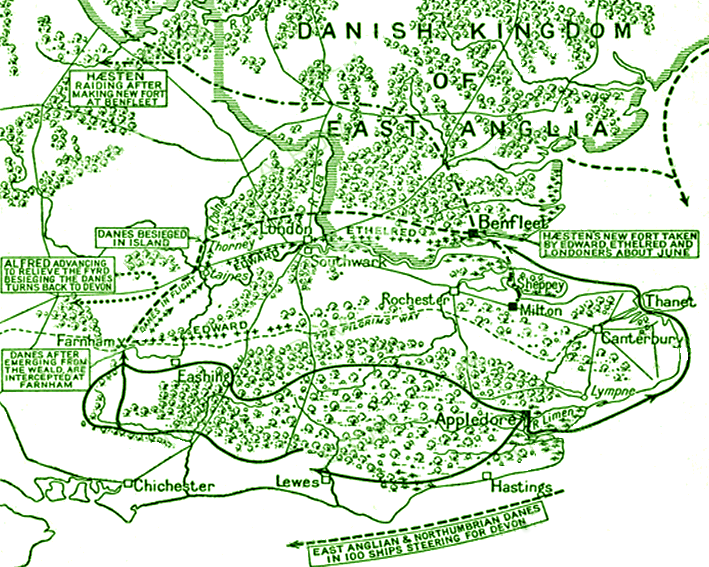

Alfred the Great’s last campaign (893)

Alfred the Great’s last campaign (893)

In the late C9, the Great Heathen Army from Denmark annexed the north of England, initiating a tribal division that persisted into the Middle Ages and beyond. Although King Alfred put a stop to the Danes’ southward encroachment at Edington in 878, the assurances he secured from the beaten enemy were broken 15 years later by a concerted invasion. Intent on settling with their families, 250 shiploads of Danes landed in the Rother estuary and established a large camp at Appledore, while 80 more disembarked from the Thames estuary at Milton. They headed west and north, but Alfred’s son Edward drove them into Essex, while the king hurried west to expel another force that had sailed from the Danelaw to take Exeter. Alfred’s son-in-law Aethelred then led an Anglo-Welsh army that crushed the remaining invaders on the Welsh borders. The English victory brought a century of relative peace, which lasted until Sweyn Forkbeard had fresh ideas in 1009.

The Sack of Canterbury (1011)

The Sack of Canterbury (1011)

Though Canterbury had more than once experienced Viking aggression, nothing prepared it for what happened in 1011. At the start of Sweyn Forkbeard’s 1009-12 campaign, his able general Thorkell the Tall had landed his army near Sandwich, intending to pillage Canterbury. The county paid him Danegeld of 3,000 pounds of silver to go away; yet, two years later, he was back. The city resisted his assault for three weeks, until the siege succeeded on account of the treachery of a certain Aelfmaer. Once in, the Vikings did all they were notorious for, including stripping the city bare, setting fire to the cathedral, and taking eminent hostages, one of them being Archbishop Aelfheah himself. After ordering his kinsmen not to pay a ransom, Aelfheah was pelted with animal bones at a drunken feast in Greenwich and murdered with an axe-butt. So traumatic was the experience that, when the Norman Vikings invaded 55 years later, Kent’s capital gave in without a fight.

Cnut’s Kentish war crime (1014)

Cnut’s Kentish war crime (1014)

When King Sweyn died after just months on the English throne, his son Cnut was quickly driven out. He set sail for Denmark, taking with him his father’s noble hostages; and, at Sandwich, he paused to put them ashore. There was however a sting in the tail. On the beach, he had their hands, noses and ears cut off. This barbarity was an act of pure spite, meant as a rebuke to the English council that had sworn fealty to his father’s rule but shunned Cnut in favour of Ethelraed the Unready. These unfortunates would be a lasting reminder to Anglo-Saxon nobles of his contempt for them. It was plainly an effective tactic: English resistance folded when Cnut returned with a large army two years later. Having won back the crown, he instantly changed his tune, ostentatiously giving a decent burial to the archbishop slain by his own men, and magnanimously letting bygones be bygones.

The 2nd Battle of Otford (1016)

The 2nd Battle of Otford (1016)

King Ethelraed II’s hapless efforts to repel Cnut’s invasion came to a halt in April 1016, when he died in London. Luckily, his son Edmund Ironside was made of sterner stuff. Though most of England had given up, the young new king took the battle to the Danes. After winning back Wessex and relieving a siege of London, he headed for Kent, where Cnut was gathering his troops on the Medway. At Otford, he won a sterling victory that saw the invaders fleeing to Sheppey. Afterwards, however, he made a tragic error at Aylesford in accepting Eadric the Acquisitive back into the Saxon fold. Within weeks, during the seminal showdown at Assandun, Eadric and his men again defected, handing Cnut a decisive victory. Edmund was forced to come to terms, and within a month was dead, by fair means or foul. Cnut became undisputed king, and for once did something laudable: he had Eadric put to death.

Godwin’s revolt (1051)

Godwin’s revolt (1051)

With his considerable estates in Kent and access to Kent’s elite fighting men, Sussex-born Godwin, Earl of Wessex (ca 1001-53) was arguably the most powerful man in England during the reign of his son-in-law, Edward the Confessor. In 1051, the King, perversely pursuing a strategic alliance with Normandy, provocatively appointed a Norman archbishop of Canterbury. When Eustace of Boulogne then arrived in Dover to take up the castellanship of the castle, a bloody uprising occurred. Outraged, Edward ordered Godwin to punish the townsfolk, but his sons marched instead on the royal court at Gloucester. There they were duped into talks, and all were banished. Returning with a Flemish army in 1052, Godwin forced the restoration of their estates and powers; but the truce proved short-lived. Edward supposedly promised the English throne to William the Bastard, setting the Norman on a collision course with Godwin’s younger son, Harold II. Their bitter encounter in 1066 would end terribly for all Britain.

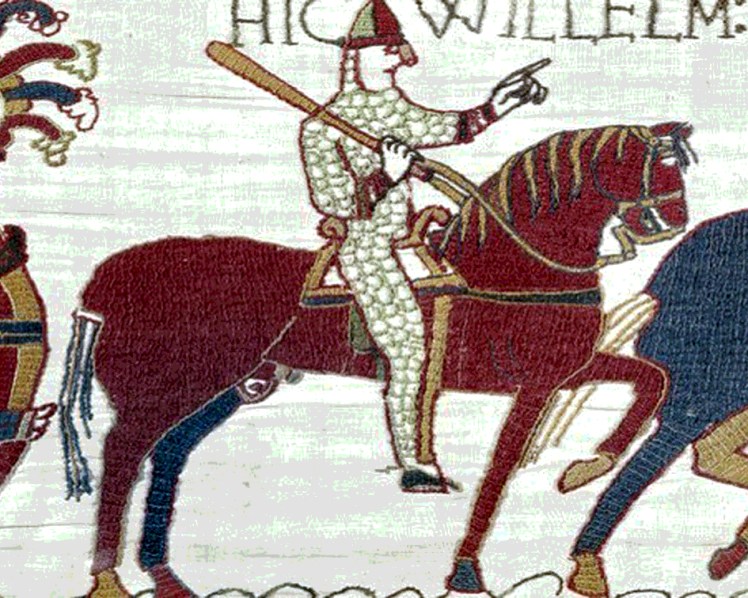

The Kentish Resistance (1066)

The Kentish Resistance (1066)

After extinguishing the English nobility at the Battle of Hastings, William the Conqueror showed zero tolerance to popular opposition. Dover and Canterbury fell without a fight. Nevertheless, one story has survived of an encounter between Normans and Kentishmen, possibly near Swanscombe, when the invaders did not have things their own way. In its crudest version, the invaders were chased out of Kent by a mob bearing staves. More subtly, a deputation approached William offering either the branch of peace or the sword of war; he opted for the former, and agreed to their demands. It may just have been symbolic of broader resistance by Kent people, but its basic truth is witnessed by subsequent events. Uniquely among counties away from the Welsh and Scottish borders, Kent was granted the status of semi-autonomous ‘County Palatine’, so retaining some of its own laws. The Conqueror was no respecter of rights, but knew a sturdy opponent when he saw one.

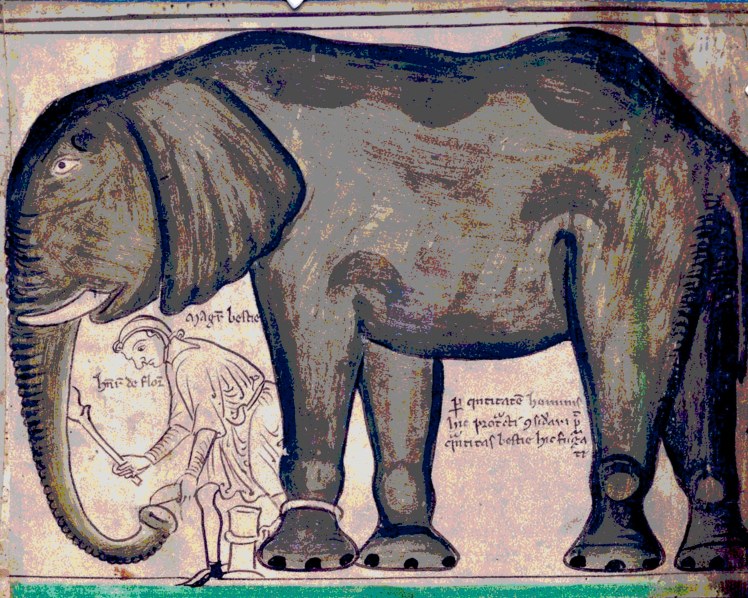

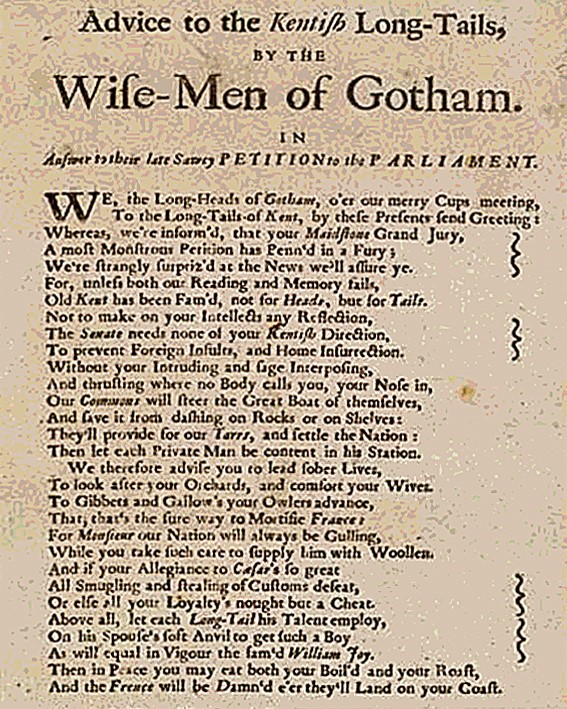

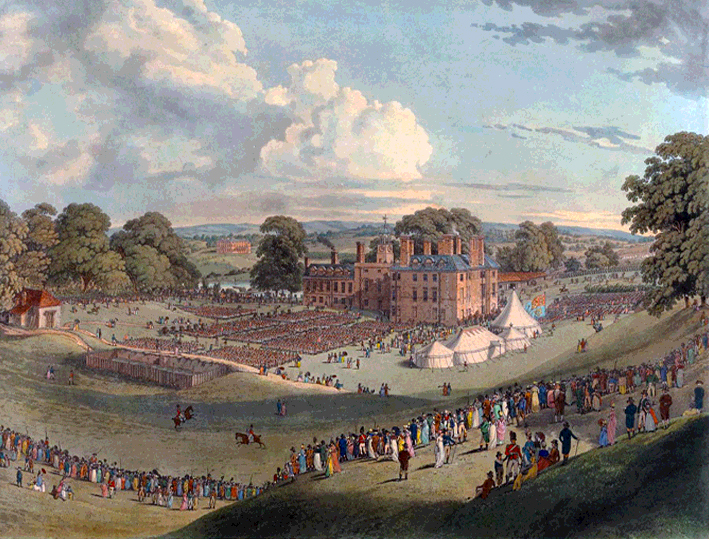

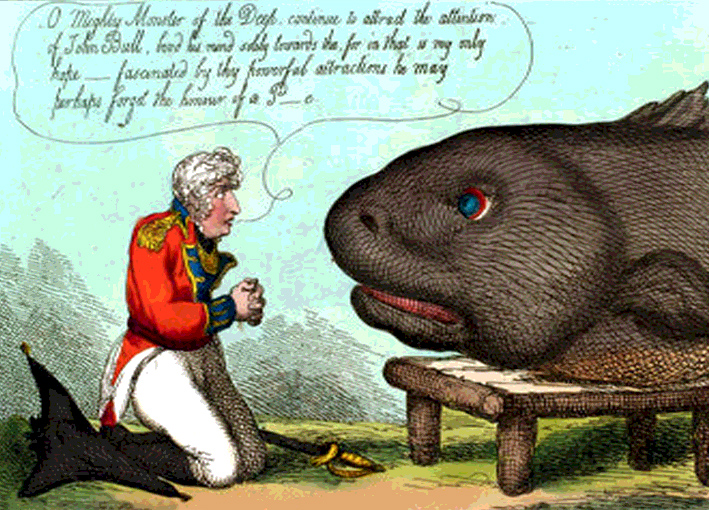

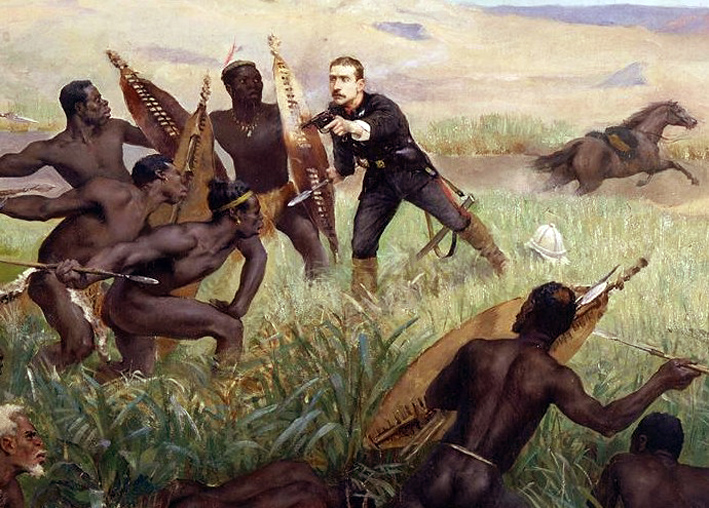

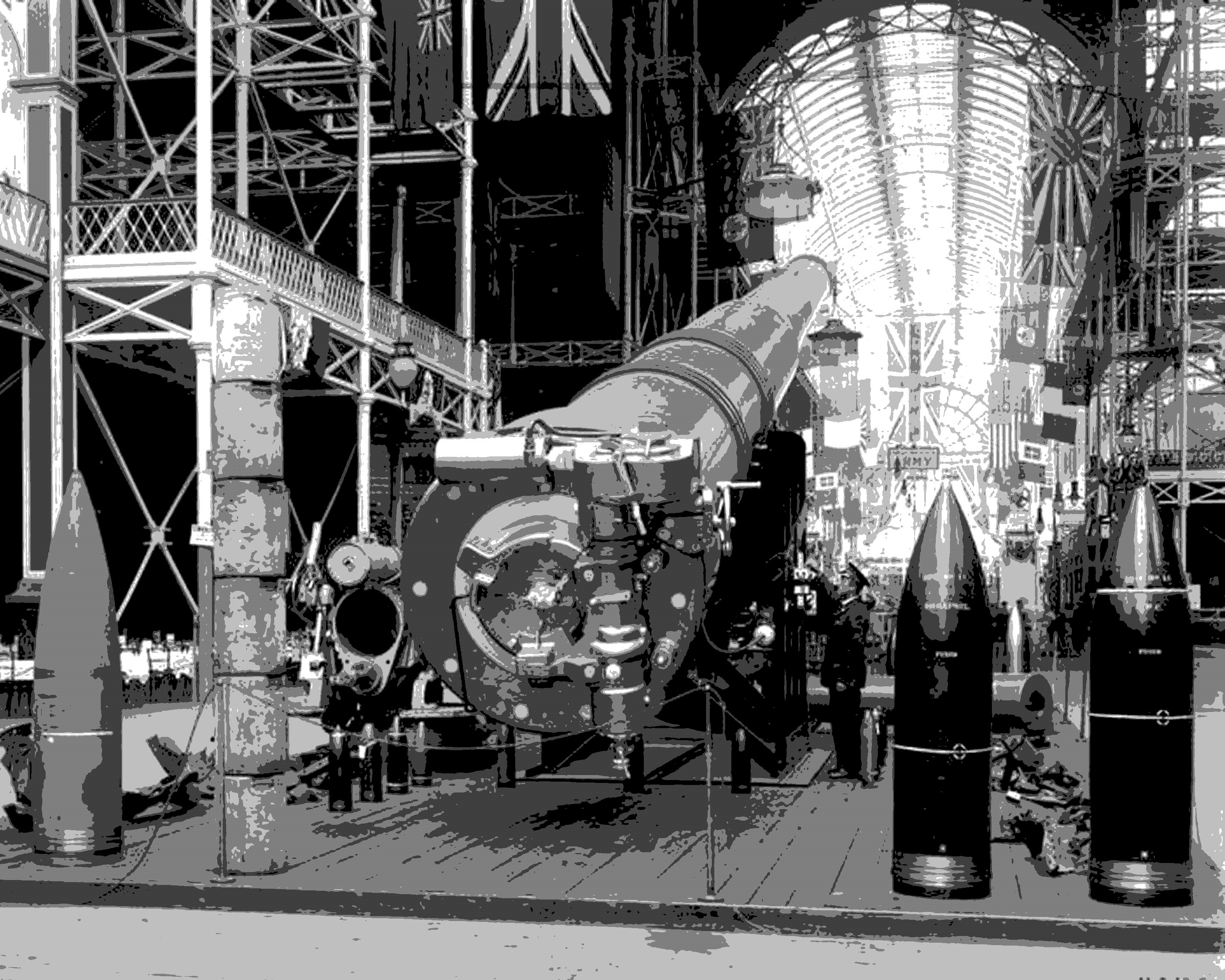

The Penenden Heath Trial (1076)

The Penenden Heath Trial (1076)

King William I’s invasion in 1066 was a historic slice of opportunism consolidated by unparalleled brutality. Because the Normans were outnumbered by about a thousand to one in their new land, he made liberal use of castle-building to overawe and oppress the populace. As the danger to himself subsided, however, he grew keen to build bridges. The first olive branch he offered was to the Church, which was hoping to recover some of its lost lands. He permitted a formal inquiry by many of the top nobles in England, even including some Saxons. It took place on Penenden Heath, north of Maidstone, and amounted to the trial of William’s rapacious half-brother Odo, who as Earl of Kent had been indicted by Archbishop Lanfranc. The nobles found against Odo and confiscated part of his possessions. William was no fool, however. Ten years later, he ordered the Domesday Survey, just so there’d be no doubt about who really owned England.

The foundation of St Bartholomew’s Hospital, Rochester (1078)

The foundation of St Bartholomew’s Hospital, Rochester (1078)

Rochester missed out on founding the world’s oldest extant school, but was compensated with Britain’s longest-running hospital. St Bartholomew’s was built by Archbishop Gundulf fifty years before its more famous namesake in London. Like the Harbledown Hospital founded six years later at Canterbury, it was intended as a leper colony, but also catered for the poor. In view of the nature of its occupants, it was built outside of the city wall in a part of Chatham under Rochester’s jurisdiction. After living mostly off the charity of the local Priory, it fell on hard times when Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries. It only recovered when the growth of the Royal Dockyard added so much to the value of the Hospital’s lands that the Crown even tried to sequestrate them. St Bart’s was expanded and modernised in the C19; but the NHS had no need for it, and it closed in 2016 amid plans for redevelopment as housing.

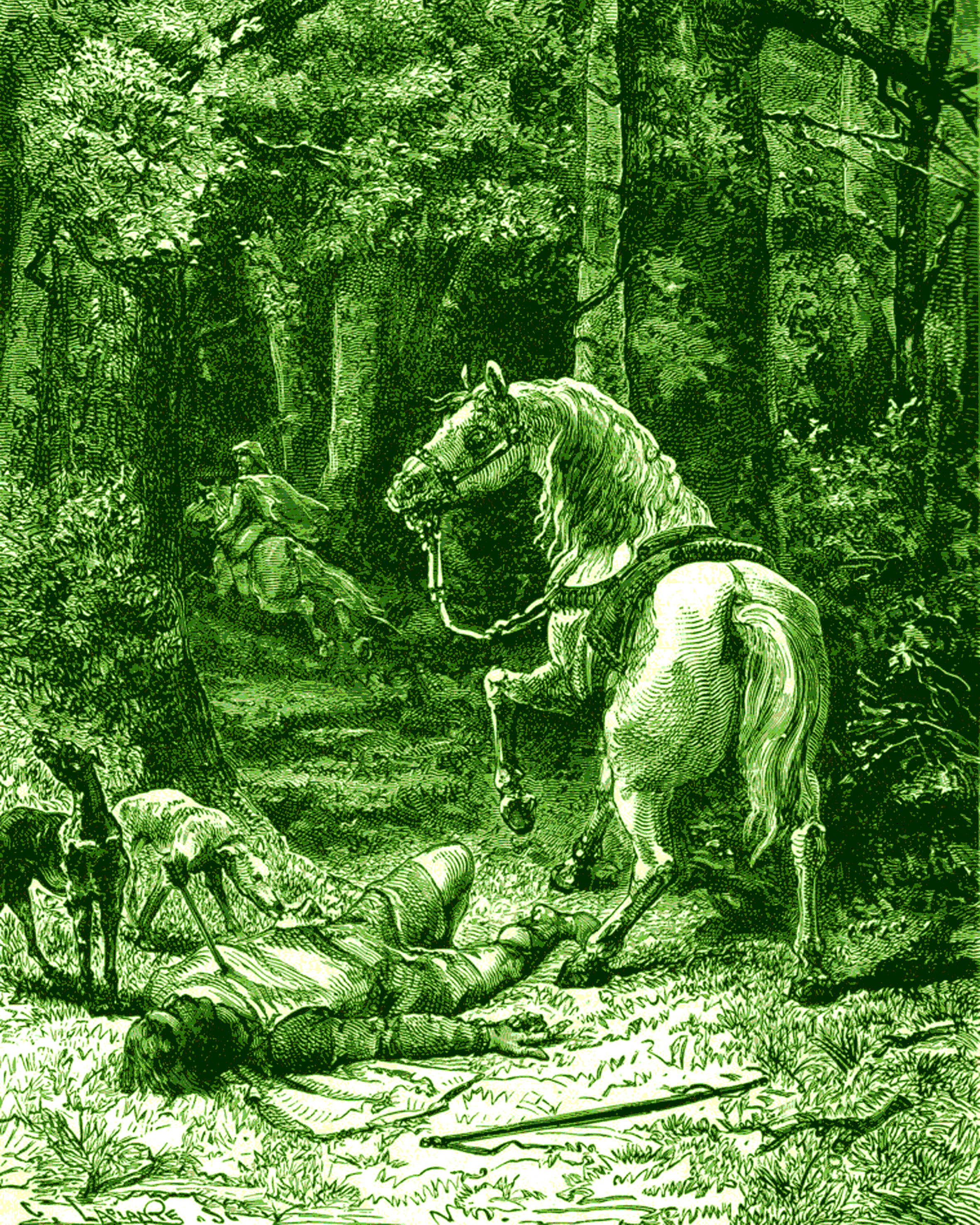

The strange death of King William Rufus (1100)

The strange death of King William Rufus (1100)

Tonbridge-born Walter Tirel, a Norman, was that rare phenomenon in English history: a regicide. Having married the daughter of the powerful Richard FitzGilbert, he found himself as close to the throne as were his brothers-in-law, the de Clares. In August 1100, they went hunting in the New Forest with King William Rufus and Prince Henry, sons of the Conqueror. Rufus gifted Tirel two new arrows, saying in Norman French, “Good archer, good arrows”; but, after the two were left alone together, the King was found dead with an arrow through his chest. Tirel had fled on horseback, and was never spotted in England again. Although the de Clares had been at war with the turbulent monarch, and Henry stood to succeed him, the chroniclers of the day – and even the Rufus Stone commemorating the deed – maintain that it was an accident: the arrow had supposedly glanced off a tree when aimed at a stag. If you’ll believe that…

The 1st Siege of Leeds Castle (1139)

The 1st Siege of Leeds Castle (1139)

Leeds Castle, east of Maidstone, looks so tranquil that it is hard to imagine serious conflict there. The first occasion was in the C12, when King Stephen seized the throne. In 1119, Robert de Crèvecoeur had erected a stone fortress there – possibly a motte and bailey – on land that had been gifted by William II to his cousin Hamo. The Crèvecoeurs supported Empress Matilda’s claim to succeed her father Henry I, and in 1139 were in an awkward position when she invaded England with French troops. King Stephen’s forces under Gilbert de Clare laid siege to the castle. Although the Castle fell, Matilda’s forces eventually engaged Stephen in 1141 at Lincoln, where he was captured; but popular resistance to her accession barred her from formally becoming monarch. The Castle was at length returned to the de Crèvecoeurs, who managed to retain it for another hundred years before the Crown pinched it for good.

Trial by combat on the Thames (1163)

Trial by combat on the Thames (1163)

Henry of Essex, Baron Raleigh, was first noted for rebuilding Saltwood Castle before 1135, he being the local lord of the manor. He occupied several official posts under King Stephen and then Henry II, and as a king’s constable enjoyed the apparently cushy job of bearing the royal standard in battle. All was well until Robert de Montfort, who was in dispute with him over an inheritance, accused him of committing treason six years earlier, alleging that he had thrown down the standard and declared the king dead during a Welsh ambush. Despite Raleigh’s denial, the king ordered that he be tried by combat, facing de Montfort in public on an island on the Thames at Reading. Supposedly distracted by two ghostly apparitions, Raleigh was soon rendered unconscious and presumed dead; but he was restored by the Benedictines from the local abbey who carried him off. Having been disinherited, he remained there as a monk until his death.

The assassination of Thomas Becket (1170)

The assassination of Thomas Becket (1170)

The murder of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, inside Canterbury Cathedral on December 29th, 1170 was a Kentish affair in more respects than the location alone. Becket, a Norman noble, had earned King Henry II’s opprobrium by repeatedly disrespecting his will. The four knights who were sent to deal with him were led by Reginald FitzUrse, who had estates at both Barham and Teston. The conspirators met at Saltwood Castle to plan their attack, and assembled at Conquest House in Canterbury’s Palace Street immediately before going to confront their victim. Although Becket had never been at all popular with the public, the manner and place of his murder caused outrage, and the Cathedral was presented with a perfect martyr who would help turn pilgrimages to Canterbury into a world-famous institution. As for the FitzUrse family, they prudently changed their name to Barham, but continued to display their bear emblem, still visible around Kent.

The Great Fire of Canterbury Cathedral (1174)

The Great Fire of Canterbury Cathedral (1174)

In 1067, months after William the Conqueror was crowned King of England, England’s foremost religious building burned to the ground. Whatever the true cause, Saxons will have seen it as a sign of God’s anger. Mysteriously, after the Cathedral had been entirely rebuilt in Norman style, there was a repeat a century later. In September 1174, the building was again engulfed in flames, suffering major damage. Whole sections had to be rebuilt, this time in gothic style; the discontinuity is easily spotted today. The fire was blamed on cinders drifting across from blazing cottages nearby. However, a historian recently suggested that the actual cause was arson: Canterbury was in competition with Durham for pilgrims’ visits, so its monks were desperate to build a new shrine to the recently murdered Thomas Becket. Perhaps; but, given the paucity of hard evidence, one might as well argue that God was reacting to the recent canonisation of the “turbulent priest”.

England’s first state visit (1179)

England’s first state visit (1179)

When 14-year-old Philip, heir to the Frankish throne, fell sick, his father Louis VII felt obligated to pray at Becket’s shrine in Canterbury Cathedral, and England’s Henry II hurriedly assembled an entourage to greet him on Dover Beach. It was a fraught encounter. Louis had been wed to Eleanor of Aquitaine, but the marriage was annulled when no son ensued, leaving her free to marry the English king. She and Louis had been close to Becket, and his murder at Henry’s ambiguous behest so infuriated her that she conspired with their eldest son Henry to rebel against the King, and urged Louis and other foreign potentates to invade; only vigorous military action had ended this Great Revolt. Now reconciled, Henry and Louis prayed before the martyr’s tomb before returning together to Dover, the unprecedented royal visit completed without mishap. Young Philip duly survived, but young Henry died unforgiven, and Eleanor remained imprisoned until her husband’s death.

The Flight of William de Longchamp (1191)

The Flight of William de Longchamp (1191)

Born in Normandy, William de Longchamp set out to ingratiate himself with Anglo-Norman royals. He worked first for Henry II’s son Geoffrey, but transferred his loyalty to the more ambitious Prince Richard. When the latter was crowned in 1189, he granted Longchamp the title of Chancellor, for which the Norman paid £3,000 when Richard went crusading shortly afterwards. Transformed overnight from non-entity to regent of England, Longchamp quickly alienated himself by refusing to learn English, living ostentatiously, and preferring his compatriots over Anglo-Normans in official appointments. Richard’s younger brother John rebelled against the upstart, who in 1191 was forced to flee the country. At Dover, where his brother-in-law was castellan, he disguised himself as a monk and then a woman, in which guise he was discovered; in another version, he was mishandled by a lascivious fisherman. Having eventually escaped, he traced the King to his place of imprisonment in Germany and paid the ransom that secured Richard’s release.

The murder of St William of Rochester (ca 1201)

The murder of St William of Rochester (ca 1201)

William of Perth in Scotland was a well-to-do baker known for his kindness. He adopted an orphan he came across at a church, naming him ‘Cockermay Doucri’ or Foundling David, and taught him his trade. His piety led him to undertake a pilgrimage to Canterbury, taking his ward with him. After they had lodged for three days at Rochester, the lad led him astray, hit him over the head, cut his throat, robbed him, and disappeared. According to legend, a madwoman found William’s body and unaccountably placed a garland on his and her own head, curing herself of her madness. The brothers of Rochester decreed the occurrence miraculous, and buried the corpse in the Cathedral. In 1256, the Bishop persuaded Pope Alexander IV to canonise William, and a shrine was built. This now world-famous tale has inevitably provoked cynical speculation that it was cooked up by prelates seeking a lucrative competitor to Becket’s shrine at Canterbury.

The Siege of Rochester (1215)

The Siege of Rochester (1215)

The signing of Magna Carta in June 1215 is usually presented as the end of a conflict. In truth, it was the start of a worse one. Marching from Dover to London in October 1215, King John found his path blocked by Rochester Castle, which controlled the river crossing. The rebel barons had taken the initiative by sending William d’Aubigny to reinforce it, and the city constable had admitted his troops. Ironically, John had commissioned expensive repairs not long before. He decided on a siege. Despite his best efforts, including lighting a fire in a mine that collapsed a corner of the keep, he could not break the defenders’ resistance. At length it was starvation that did for them. Apart from cutting off the hands and feet of some who had agreed to leave the castle early, the King was persuaded to treat his prisoners with uncustomary clemency. It was however the beginning of the end for him.

The French Invasion (1216)

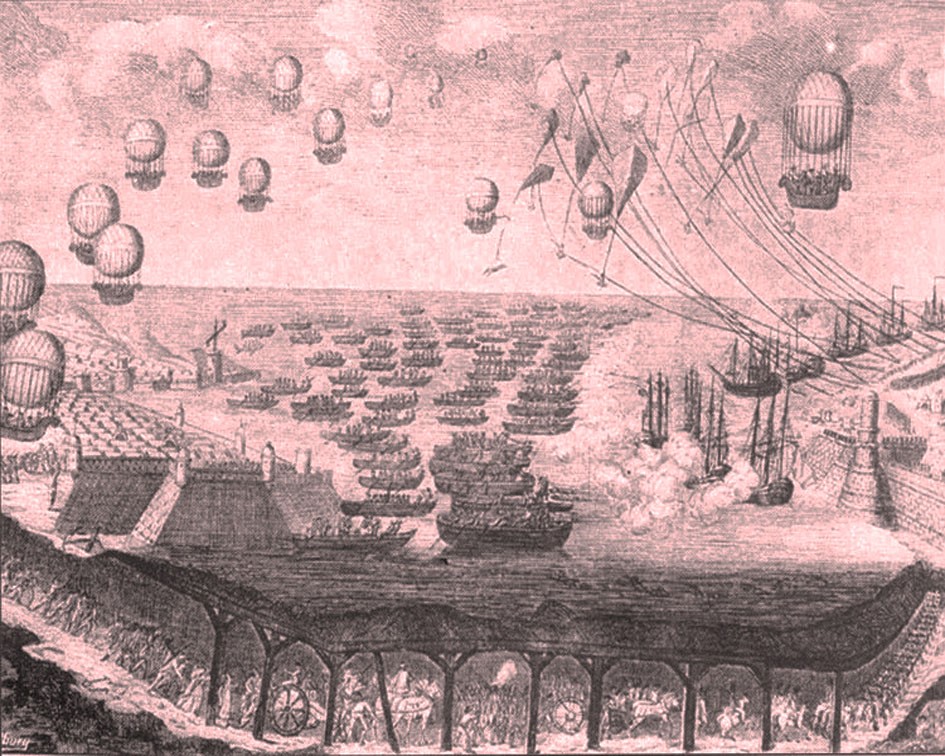

The French Invasion (1216)

The First Barons’ War (1215-17) was a civil war on English turf between Normans loyal to the atrocious King John and Normans prepared to do anything to dethrone him. The barons who’d forced the King’s hand at Runnymede were still unhappy, and next invited Louis, son of King Philippe II of France, to join them in deposing the King of England. Ignoring his father’s and the Pope’s warnings, Louis sent a vanguard of knights to London, and then an invasion fleet. His army landed in Thanet in May 1216. King John abandoned the county to its fate, and Louis marched unopposed to the capital. Like Hengist before him, he had arrived as a mercenary, but now had an appetite for conquest. He was proclaimed King of England by his supporters, and went off to suppress much of the South, while John skulked in the West. Nevertheless, Louis and Kent still had unfinished business.

The Siege of Dover (1216-7)

The Siege of Dover (1216-7)

Although young Prince Louis’s exploits in England had earned him the sobriquet ‘le Lion’, the war was not over. He had Canterbury and Rochester under his control, but the crucial port of Dover was still holding out. In July 1216, he headed back east to remedy the omission. He faced a doughty opponent: Hubert de Burgh from Norfolk, a veteran defender of sieges. The French successfully undermined the Castle barbican, and then brought down one tower of the gatehouse; but their massed assault was bloodily repulsed. After failing to starve the defenders out, Louis agreed a truce in October. King John died four days later, but de Burgh continued to resist on behalf of child king Henry III. Louis departed the scene, returning in May 1217 to renew his assault with a huge siege engine. Resistance remained fierce, however, both from the sea and Willikin of the Weald’s heroic guerrilla warfare. This time, Louis gave up for good.

The 2nd Battle of Sandwich (1217)

The 2nd Battle of Sandwich (1217)

De Burgh’s indomitability at Dover Castle tied up the invaders’ resources so seriously that Prince Louis’s allies in the North were emphatically defeated at Lincoln. After retreating to London to regroup, Louis sent for a supply fleet from France. It was commanded by mercenary pirate Eustace the Monk, carrying troops commanded by Robert de Courtenay. On August 24th, de Burgh led the English fleet, using a battle-plan worthy of Nelson. He allowed the heavily laden French fleet to pass Sandwich before setting sail, looping behind them to attack from the windward. English archers used the wind to wreak havoc, whilst lime was released into French eyes. The invaders were routed, and Eustace was beheaded on deck. Louis renounced his claim to the English crown and went home; there’d be no King Louis I of England after all. He’d been beaten by Kentish pluck, on land and at sea. In its consequences, it was like Waterloo and Trafalgar combined.

The Marian Apparition at Aylesford (1251)

The Marian Apparition at Aylesford (1251)

St Simon Stock (d 1265) was a supreme ascetic, living in a hollow tree at Aylesford on water, herbs, roots, and apples. According to Catholic legend, the Virgin Mary appeared to him on July 16th, 1251 and gave him a brown scapular – a cloak now closely associated with Carmelites, the order of monks that sprang from hermits in the Mount Carmel range in Palestine. England’s first Carmelite priory had been founded at Aylesford in 1242 by returning crusader Ralph Frisburn, and Stock duly became its prior general in 1254. He died and was buried in Bordeaux, though a fragment of his skull was sent to be enshrined at Aylesford in 1951. Claims that the apparition was a later invention were refuted by a Carmelite friar in 1642, but his written evidence proved a forgery. Nevertheless, Pope John Paul II lauded the tradition in 2001, the 750th anniversary. Stock is remembered in the name of a Catholic school in Maidstone.

An elephant fit for two kings (1255)

An elephant fit for two kings (1255)

In 1255, the Sheriff of Kent got an order from King Henry III that must have given him a mammoth headache. There’s an elephant waiting near Calais, it said, and you’re to get it to the Tower of London for my menagerie. The county had little practice in shifting pachyderms around, its only previous experience being one that arrived at Sandwich with the Romans in AD 43. This one was a gift from Henry’s French brother-in-law, Louis IX. It was ten years old and ten feet high, and Louis had been gifted it by the Egyptians, who were after an alliance against the Syrians. It’s not recorded whether the Sheriff ferried it straight to Deptford, or landed it at Dover and made it walk; but he did rack up nearly £7 in expenses. There’s a story that it made mincemeat of a Kentish bull that took umbrage at its presence, though that may just be a rural myth.

The great South England flood (1287)

The great South England flood (1287)

Anyone wondering why Tenterden is a Cinque Port nine miles inland need look no further than the flood of 1287. During the C13, there were six violent storms that wreaked havoc with Kent’s southern coastal towns. The mother of them arrived in February 1287, striking with such violence that there was widespread flooding. The subsequent sedimentation changed the coastline dramatically, not least by filling in the bight beside which Tenterden sat. Also affected was New Romney, hit by an avalanche of gravel that physically moved the town a mile inland. The Rother found a new outlet at Rye, which was elevated to the status of a Cinque Port at New Romney‘s expense. Also in Sussex, Winchelsea was obliterated, and had to be rebuilt on the top of a cliff, while Hastings lost its harbour when a cliff collapsed. Even so, England could consider itself lucky. That same year, a storm further east caused the death of 50,000 in Holland.

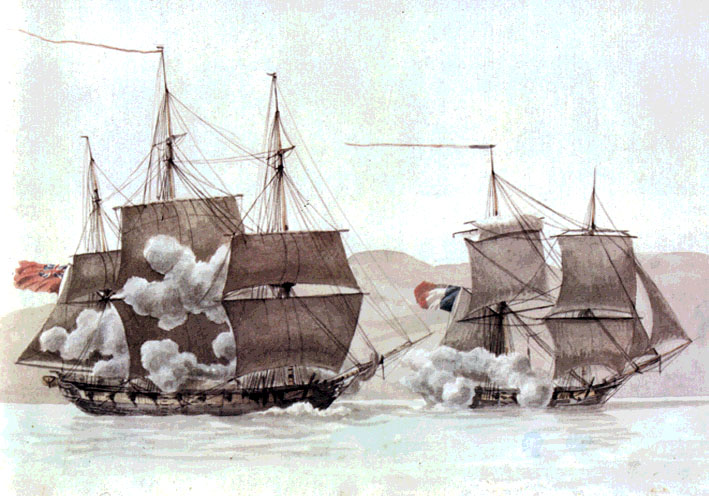

The battle of Pointe Saint-Mathieu (1293)

The battle of Pointe Saint-Mathieu (1293)

Even before the creation of the United Kingdom, English fleets had by far the better of nearly two dozen major sea-battles with France during five centuries when the two were seldom at peace, despite France’s far greater territory, population, and resources. One of the most striking demonstrations of English seamanship and martial spirit occurred in 1293. It all started when a Norman and a Bayonnais (then English) ship arrived simultaneously at a Breton spring. A dispute arose over priority of access, and a Frenchman was killed. The Normans and French conducted a series of such horrific reprisals on English merchant vessels that the semi-autonomous Cinque Ports, disregarding Edward I’s peace efforts, gathered a fleet of 100 vessels bent on vengeance. On May 15th, these ‘Portsmen’ engaged a 200-strong French fleet off Britanny, and sank or captured practically all of it. The French humiliation catalysed the nine-year Gascon War, eventually settled by royal marriages.

The 2nd Siege of Leeds Castle (1321)

The 2nd Siege of Leeds Castle (1321)

Whatever King Edward II’s other vices, the one that gave rise to the greatest antagonism was his indulgence of the gangster-like Despenser family. Kent-born Bartolomew de Badlesmere, who had been granted stewardship of Leeds Castle, joined the party of barons opposing them. While he was at Oxford attending a meeting of these ‘Contrariants’, the blue touchpaper was lit. The King got his wife Isabella to detour to Leeds and demand to be accommodated. This was a smart move, because Badlesmere’s wife Margaret was known to detest her. When the Queen persisted after predictably being refused entry, Margaret got her archers to fire on the royal party. Six were killed. The King mounted a major siege that the Contrariants opted not to interfere with. Margaret surrendered after a fortnight and became the first woman to be imprisoned in the Tower. Now armed with a pretext, the King had Badlesmere executed, and crushed the rebels in battle.

The Banquet of the Four Kings (1364)

The Banquet of the Four Kings (1364)

The ‘Banquet of the Five Kings’ sounds a grand coming-together, especially when you are told it was organised by a former Lord Mayor of London and hosted by the Vintners’ Company, which had just received its Royal Charter. The snag is that it never happened. The host, Edward III, was around, as were the French king John II, a long-term hostage, and David II of Scotland, a former prisoner but also Edward’s recently widowed brother-in-law. A third guest, Valdemar IV of Denmark, turned up en route to France; but the last of the five, Peter I of Cyprus, had already left before Christmas. Edward did however entertain the others on the 12th day of Christmas, 1364 in the great hall at Eltham Palace. We know this because it is commemorated in a stained-glass window. Poignantly, although Edward was comfortably the oldest, he would outlive them all.

The Peasants’ Revolt (1381)

The Peasants’ Revolt (1381)

The Black Death of 1348 killed half the population of England. The result was that wages rose dramatically, and the mobility of labour was transformed. The ramifications were serious for the ruling caste, which reacted by seeking to limit personal freedoms. Coincidentally, the Hundred Years’ War was going badly, and a series of poll-taxes designed to raise funds exacerbated popular hostility. When the people of Brentwood in Essex refused to pay, there was open unrest, prompting a general insurgency across the South-East. The flashpoint was the imprisonment of Robert Belling, an escaped serf from Gravesend. Rebels released radical preacher John Ball from Maidstone Gaol and marched on Rochester Castle, successfully freeing Belling. Wat Tyler took control of the revolt, capturing Canterbury and assembling an army at Blackheath before causing mayhem in London. He overreached himself, however, and was killed at Smithfield. Without his leadership, the rebellion fizzled out. The debacle nevertheless remains a landmark in the revolutionary mythos.

The Dover Straits earthquake (1382)

The Dover Straits earthquake (1382)

Although the North-West of Europe is not normally associated with newsworthy seismic activity, an area of instability does exist to the east of Kent. On May 21st, 1382, it was the epicentre of an earthquake that caused structural damage as far away as London. There is no record of a tsunami, but the quake is estimated to have been in the region of 6 to 6.5 on the Richter scale. The effects in Canterbury were considerable, including the partial collapse of St Augustine’s Abbey and the Cathedral. Even as far away as Hollingbourne, the church and manor suffered serious damage. Fortunately, no deaths were recorded. The earthquake occurred a year after the Kent-based Peasants’ Revolt, and was a sure sign of God’s displeasure with either the King or the rebels, according to perspective. Certainly it disturbed the ‘Earthquake Synod’ in Blackfriars, where the Archbishop of Canterbury construed it as a portent endorsing the persecution of supposed heretics.

The battle of Margate (1387)

The battle of Margate (1387)

The Channel couldn’t stop the Norman invasion in 1066, but the new ruling caste’s bellicosity, combined with Anglo-Saxon hardiness, proved a tough nut to crack thereafter. Among the several would-be conquerors thrown up by Europe over the centuries, one of the earliest was the French protector Philip the Bold, who in 1386 assembled an invasion army of 30,000 in Flanders. After illness forestalled his plans, part of the vast fleet he had gathered was used to escort French, Dutch, and Spanish merchant shipping in the Channel. In March 1387, Richard Fitzalan, the Earl of Arundel, sailed from Sandwich with 51 ships and attacked a ~300-strong convoy off Margate. What enemy ships were not captured or scattered were driven into Sluis harbour. Fitzalan followed them in and, like a true-born Viking, burned and pillaged for a fortnight. The merchant ships he captured yielded 8,000 tons of wine that was sold off cheaply in London, sealing his popularity.

The martyrdom of William White (1428)

The martyrdom of William White (1428)

Since time immemorial, political tyranny has operated by propagating a rigid orthodoxy that all interested parties will unquestioningly parrot, no matter how irrational, but whose very unreasonableness invites overt rejection by opponents; the point being that they can then be identified, judged criminal, and eliminated. In the centuries following the Norman Conquest, the approved orthodoxy was religious. A typical casualty was William White, a supporter of Wycliffe‘s anti-establishment doctrine, who moved from Kent to Ludham, Norfolk to preach it. In 1428, he was arrested as a Lollard, tried at Norwich, found guilty of heresy, and burned alive at Lollard’s Pit outside the city walls, doubtless to the satisfaction of the complaisant masses. If a charge of heresy would not stick, there was always treason, while the relatively few female dissenters could be mopped up as witches. The Norwich Heresy Trials continued for three years, and saw 51 men and nine women brought to injustice.

The Eleanor Cobham witch trial (1441)

The Eleanor Cobham witch trial (1441)

El & Humph were the C15 supercouple. He was the Duke of Gloucester, uncle and protector of the boy King Henry VI. She, a lady-in-waiting to his wife Jacqueline d’Hainault, was his mistress. After divorcing Jacqueline, Humphrey settled with Eleanor at Placentia Palace in Greenwich, where they ran a celebrated court frequented by the artistic slebs of the day. She was known for beauty and wits, he for sophistication and hedonism. When he became heir presumptive to the throne, however, things turned nasty. Eleanor was accused of witchcraft after being told by three astrologers that the King would soon die. Convicted of treason, the three were executed, and she was made to do a harlot’s public penance before being jailed for life. An old woman who complained at Blackheath about the King’s treatment of her was rewarded with execution. ‘Good Duke Humphrey’ himself was forced to divorce Eleanor, and in 1447 died while under arrest for treason.

The Battle of Formigny (1450)

The Battle of Formigny (1450)

Nearly 400 years after the Norman Conquest, the Anglo-Normans finally lost their homeland to France. They had enjoyed glittering successes under Henry V, but his peace-loving son was unfit to rule. Spotting their opportunity, the French went on the offensive, winning immediate successes. An army despatched to Normandy to repel the threat engaged the French at Formigny, enjoying a small numerical supremacy that promised victory. The French, however, deployed cannon for the first time. As these were out of bow range, English soldiers went to capture them, but while dragging them back were attacked by French cavalry. Their formation broken, the English were picked off piecemeal, and 500 prisoners massacred. Three years later, the Hundred Years War ended, with Normandy permanently lost. Ironically, given Kent’s famous antipathy to Norman rule, the inexperienced commander at Formigny, Sir Thomas Kyriell of Westenhanger, was reputedly descended from an original companion of the Conqueror.

Jack Cade’s Rebellion (1450)

Jack Cade’s Rebellion (1450)

Jack Cade was called the ‘Captain of Kent’ for good reason. By 1450, the rule of Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou was already known as much for ineptitude as for brutality. It was Jack Cade, said by Shakespeare to be from Ashford, who organised a distinctively Kentish uprising. He circulated a manifesto called ‘The Complaint of the Poor Commons of Kent’, airing the people’s grievances. Among them was being blamed for the death of the corrupt Duke of Suffolk, who had been washed up on the Kent coast. Ignored, Cade convened an army of 5,000 at Blackheath. What followed was something of a replay of 1381: a march on London, initial military successes, and revolutionary justice, followed however by a lack of self-restraint that alienated the locals. Badly beaten on London Bridge, the rebels withdrew; Cade was hunted down and slain. Though crushed, Kent’s rebellion paved the way for the Wars of the Roses five years later.

The Sack of Sandwich (1457)

The Sack of Sandwich (1457)

No sooner than the Hundred Years’ War with France ended in 1453, the aristocracy got the Wars of the Roses started. After King Henry VI was captured in 1455, a sort of peace descended; but his French wife Margaret of Anjou continued to agitate for civil war. The supportive King of France sent a fleet from Honfleur under the command of Pierre de Brézé, a veteran antagonist of the English army. His 4,000 men put ashore at Sandwich on Sunday, August 28th, 1457. The unsuspecting townsfolk found themselves on the end of a Viking-style raid as the invaders ran amok. Apart from pillaging and burning down the town, they murdered John Drury, the mayor – a deed commemorated in the town mayor’s black robe today. Sandwich, which had been England’s biggest trading port outside London, never got over it. The motives of the French are unclear, though it could have been a pre-emptive strike in support of the baguette.

The 3rd Battle of Sandwich (1460)

The 3rd Battle of Sandwich (1460)

The last and best remembered sea-battle off Sandwich occurred in 1460 during the Wars of the Roses. In October the previous year, Henry VI had won a walkover at Ludford Bridge, resulting in the flight of the Earl of Warwick and the future King Edward IV to Calais. By January, the royal Lancastrian fleet under the command of Maidstone-born Earl Rivers was at anchor off Sandwich. At dawn on January 15th, Sir John Dynham under Warwick’s command mounted an attack while the Lancastrian officers were still asleep. So total was the surprise that the King’s key ships were captured, along with their cannon, and Warwick was able to land his army at Sandwich. Having already made himself a hero in Kent by clearing the coast of pirates, he picked up many extra recruits on his way through Canterbury and Wickhambreaux. He marched his men to Northampton, where in July he won a major victory over the King.

The death of Sir Thomas Kyriell (1461)

The death of Sir Thomas Kyriell (1461)

An East-Kent counterpart to the de Clares of Tonbridge, the de Criol family of Westenhanger Castle was a significant force following the Norman Conquest. When the Wars of the Roses started, its paterfamilias was Sir Thomas Kyriell (b 1396) – the surname having been Anglicised – who had fought for Henry V in the Hundred Years’ War but been routed and surrendered at the decisive Battle of Formigny. Following his release, he became MP for Kent. Loath to support Henry’s clueless Lancastrian son, Henry VI, he joined the Yorkists at the 2nd Battle of St Albans. Being too old to fight, however, he was left to guard the King, who was then the Yorkists’ prisoner. When the battle was lost, the truculent Queen Margaret told her seven-year-old son to decide how Kyriell should die. Even though Kyriell had pledged to defend him, the King did not intervene. The unfortunate Kyriell was beheaded, and the family estate passed to his son-in-law, John Fogge.

Buckingham’s Revolt (1483)

Buckingham’s Revolt (1483)

Although Richard III was killed at Bosworth, Leicestershire, the seeds of his demise were sown in Kent. The Yorkist king Edward IV’s wife Elizabeth was one of the powerful Woodvilles who owned The Mote, Maidstone. After Edward’s sudden death, Richard imprisoned her young sons Edward and Richard in the Tower and executed their guardian, her brother Lord Rivers. Appalled, Elizabeth’s brother-in-law Lord Buckingham organised a revolt in the South-East, to be supported by his invasion from Wales and his cousin Henry Tudor’s from Brittany. When news emerged of young Edward’s murder, however, Wealden supporters came out prematurely, alerting Richard to Buckingham’s defection. He intercepted 5,000 rebels led by Richard Guildford of Cranbrook from Penenden Heath to Gravesend via Rochester, and the invasions were prevented by floods and a storm respectively. Buckingham was executed, Guildford and his associates were attainted, and Henry Tudor had to bide his time. In 1485, however, with sentiment against Richard hardened, the tide would turn.

The Battle of Deal (1495)

The Battle of Deal (1495)

The unknown fate of Edward IV’s two ill-fated sons, the unfortunate ‘Princes in the Tower’, presented a fine opportunity for fraud. The unlikely perpetrator, Perkin Warbeck (ca 1474-99), was from Wallonia and had learned his English in Ireland. Although his claim to be Richard, Duke of York was preposterous, he was promised support by several foreign parties hoping to see Henry VII deposed. With the King away in Lancashire, Warbeck set off for England with a shipload of mercenaries in the belief that the rebellious people of Kent would flock to his banner. By chance, he arrived at Deal, where the locals proved too canny for him. Discerning that his supporters were no loyal Englishmen, they lured them ashore, laid into them, and took 160 prisoner. Warbeck prudently stayed aboard and escaped. He tried his luck again four years later in Cornwall, and this time was captured. He escaped from the Tower, but was recaptured and hanged at Tyburn.

The Battle of Deptford Bridge (1497)

The Battle of Deptford Bridge (1497)

Although the Cornish Rebellion of 1497 is fashionably pitched as a Celtic nationalist revolt against the English monarch, it was in truth an armed protest against tax rises that was hijacked by a disgruntled minor aristocrat called James Tuchet, the 7th Baron Audley. When Henry VII sought to raise funding for England’s defences against threatened invasions by both the Scots and the pretender Perkin Warbeck, a 15,000-strong peasant army was raised in Cornwall, and marched on London. The rebels were met halfway by Audley, who took over command. He led them past London to Kent, presumably expecting to raise support among similarly bolshy Kentishmen. In fact, the reverse happened. On June 27th, he was met at Deptford by a vastly superior force, having also suffered many desertions on the way. The battle was lost, Audley was executed, and reparations were exacted. The king did eventually relent, whilst acknowledging Kentish loyalty by redeveloping the historic Placentia Palace at Greenwich.

The Lollard heresy trials (1511-2)

The Lollard heresy trials (1511-2)

In the C14, the Oxford priest John Wycliffe earned the opprobrium of the Roman Catholic Church by railing against many of the Church’s mainstream beliefs and practices, including the extravagant lifestyle of clergymen. He even translated the Bible into English so as to demystify it. He was in effect a harbinger of the English Reformation. The Church reacted in the normal manner of centralised authority, by declaring this challenger a devil and his followers idiots. They were in fact called ‘Lollards’, meaning something like ‘Mumblers’. But insults were not enough. In 1511, the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Warham, took a zero-tolerance stance. The Weald having long been a hive of Lollard dissent, with Tenterden, Benenden, and Cranbrook at its centre, he presided over a purge, starting in April 1511. 53 suspects were tried, of whom all bar five abjured their error and were made to do penance. The five, however, endured a single visit to the stake.

‘A Supplication for the Beggars’ (1529)

‘A Supplication for the Beggars’ (1529)

Kent-born Simon Fish is known for one thing: his highly polemical 16-page diatribe against the Catholic Church known as ‘A Supplication for the Beggars’. Like all partisan proclamations today, it was coated in populist politics to garner mass support. In practice, it was another incendiary stimulus to Protestant revolt against Catholicism, twelve years after Luther’s ‘Ninety-Five Theses’. Entirely uncompromising, it inveighed against the tyranny of Rome in general, but specifically against the concept of purgatory, which had no basis in the Bible, and the practice of selling indulgences for financial benefit. Accused of unscrupulously enriching itself at the expense of the poor, the Church reflexively declared Fish a heretic, while Sir Thomas More wrote a verbose refutation. They never got the chance to fry Fish, however, because he died in 1531 of bubonic plague. Nevertheless, a year later they had the satisfaction of publicly burning James Bainham, another Protestant revolutionary who had married Fish’s widow.

The burning of John Fryth (1533)

The burning of John Fryth (1533)

John Fryth was born at Westerham in 1503 and attended Sevenoaks Grammar School before going to Eton. At Cambridge, he encountered the new thinking that had ignited the Reformation, and probably first met William Tyndale, who greatly influenced him. These being intolerant times, he was one of ten arrested and confined in a fish cellar. After his release, he left for Antwerp, and in Germany took to writing patently heretical tracts. Their mocking tone provoked the vindictive Sir Thomas More into ordering his arrest on his arrival back in England. Challenged to confirm his faith in both purgatory and transubstantiation, Fryth refused on the grounds that neither was authenticated by the Scriptures. He was condemned even by his former tutor at Cambridge, the Bishop of Winchester, and burned at Smithfield with a young Faversham tailor, Andrew Hewet. St Mary the Virgin in Westerham still houses the font where he was baptised, a John Fryth Room, and the John Fryth Singers.

The incorporation of Maidstone Grammar School (1549)

The incorporation of Maidstone Grammar School (1549)

Maidstone, now Kent’s county town, had a school at the ecclesiastical College of All Saints as early as 1395. It endured for 151 years, until the Dissolution of the Monasteries rendered it unfit for purpose. In 1549, however, the town was incorporated under Henry VIII’s short-lived son and successor Edward VI, permitting the establishment of a new grammar school at the Corpus Christi Hall in Earl Street. It remained in this location until 1870, when a larger and quieter replacement was built off the Tonbridge Road west of the river; but this too was replaced just sixty years later by the more spacious building that forms the hub of the current school. MGS will therefore celebrate its quincentenary within 30 years. The first grammar school in Kent, it set a precedent for the likes of Dartford Grammar School (1576), Norton Knatchbull School (1630), and the Harvey Grammar School (1674), making Kent a grammar-school hotbed.

The burning of Joan Boucher (1550)

The burning of Joan Boucher (1550)

Anabaptism is the credo that baptism is invalid for candidates who have not professed their belief. Being outside of mainstream Protestantism (the Amish sect being typical), C16 Anabaptists were as unpopular with the Church of England as with Roman Catholics. Joan Boucher, from Romney Marsh, may have been descended from Anabaptist refugees from persecution on the continent. She became an outspoken champion of her faith, and was briefly jailed for her critique of the Eucharist. Five years later she was convicted of heresy and sentenced to death. The following year saw numerous attempts by leading church figures to persuade her to recant, which would have made for good propaganda. She steadfastly refused. Royal chaplain John Rogers declared that beheading was too good for her, and she was burned at the stake. The ironic twist was that, with Mary I on the throne five years later, Rogers suffered the same fate: a case of the burner burnt.

The murder of Arden of Faversham (1551)

The murder of Arden of Faversham (1551)

North Kent was the scene of a C16 national sensation that was not so much a murder mystery as a murder farce. Alice Arden of Faversham decided with her low-born lover Thomas Mosby to murder her husband, former mayor Thomas Arden. After several failed attempts, she hired a couple of assassins called Black Will and Shakebag to do the job professionally. More botches followed before they finally succeeded; but they left the body in a field in a snowstorm, apparently unaware that their tracks would be left visible. The hitmen fled, but Arden and Mosby were tried and sentenced to death. Strangely, though he was hanged, she was burned at the stake, having been found guilty of ‘petty treason’ against a superior, namely a man. So dramatic were these events that they inspired an anonymous 1592 play, now thought to have been written mostly by William Shakespeare himself. The Bard, coincidentally, had an ancestor called Thomas Arden who’d died shortly before.

Wyatt’s Rebellion (1554)

Wyatt’s Rebellion (1554)

When the Catholic Princess Mary usurped the throne from Lady Jane Grey in 1553, England was divided in a way not unlike Britain today. The flashpoint was her decision to marry the Catholic King of Spain, Philip II, prompting a conspiracy by Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger, Sir Peter Carew, Sir James Croft, and Lady Jane’s father, the Duke of Suffolk. Their four armies were to converge on London from Kent, Devon, Herefordshire, and Leicestershire respectively. Wyatt was left isolated when the plot was exposed, but assembled an army of 1,500 men “of the best shire” at Rochester. Although 500 rebels were initially routed at Hartley Wood, many Royalist troops defected, as did militia sent from London. Wyatt’s 4,000-strong force was nevertheless repulsed at Southwark by London loyalists, and instead crossed the Thames at Kingston. They were again thwarted by Londoners at Ludgate, and disbanded. Like Lady Jane and 90 fellow rebels, Wyatt received no mercy.

The executions of the Canterbury Martyrs (1555-8)

The executions of the Canterbury Martyrs (1555-8)

A big issue facing Christianity from the start was predestination. If all was pre-ordained by God, where did that leave free will? The consensus was that God’s will was supreme, but there was endless dispute about the detail. Reformation theologians generally went along with Catholicism on this; but a major challenge was presented by the Freewillers. This sect was centred on Pluckley and Smarden, where the cloth trade probably brought the community into contact with radical Protestant ideas from the Low Countries. It brought the first schism in Protestantism, exacerbated by the fact that it was able to run its own separate services. Its leader, Henry Hart, wrote passionate texts concerning free will, albeit not very articulately. Needless to say, Mary I took a very prejudicial point of view. Some members were burned in Canterbury; but, by the time the order for Hart’s arrest went out in 1557, he was already dead. The sect left no trace.

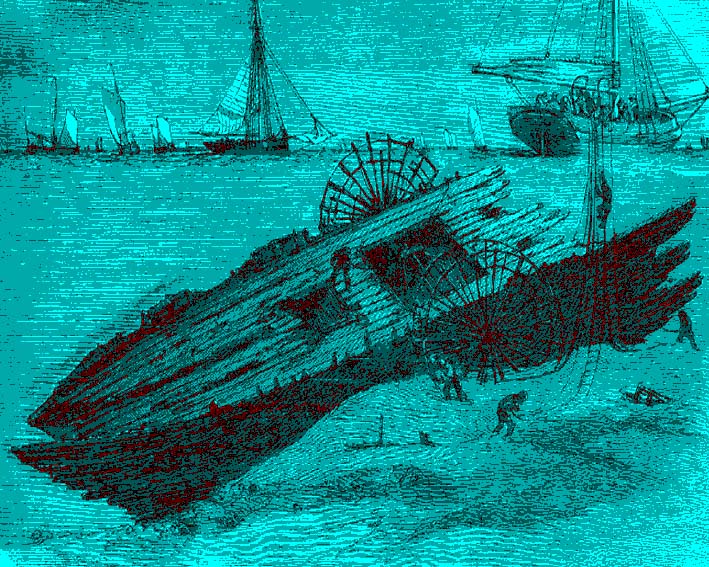

The wreck of the Greyhound (1563)

The wreck of the Greyhound (1563)

In 1553, Sir Thomas Finch from the Moat, Canterbury, helped put down Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger’s revolt. Ten years later, he was sent as knight marshal to reinforce English fortifications erected in Le Havre in support of a Huguenot uprising. The 200 who embarked on the galleass Greyhound included other well-connected nobles. Driven back by adverse winds, they attempted to land at Rye, but were wrecked on a sandbar; all but seven men drowned. The loss of Finch, who was buried at Eastwell, was considered grievous. The disaster was lent added poignancy by the death of another on board, who was possibly related to the Brookes of Cobham Hall. A young poet called Arthur Brooke, he had written ‘The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet’ – the main source for Shakespeare’s classic play – only the year before.

The Huguenot migrations (1572/1685)

The Huguenot migrations (1572/1685)

‘Huguenot’ was another religious name coined as a term of derision. Its origins are obscure, but it described the French Calvinist Protestants who by the mid-C15 amounted to two million – roughly 10% of France’s population. Their growing strength provoked a Catholic backlash, culminating in 1572 with the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. Tens of thousands of Huguenots were slaughtered, prompting an exodus. A favoured destination was Elizabethan England, with its sympathetic Protestant work ethic. Although Sandwich’s population was already swollen by Dutch Protestant immigrants, poor Huguenot refugees were awarded 50 shillings by the authorities. More stayed in Dover, but most moved on to Canterbury, which acquired the largest foreign population outside London. This sudden influx brought unrest over overcrowding, crime, and preferential treatment for ‘strangers’, but the Government prized the immigrants’ commercial worth, especially as weavers. There would be a larger influx a century later, when Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes that had halted the persecution.

Queen Elizabeth’s Royal Progress into Kent (1573)

Queen Elizabeth’s Royal Progress into Kent (1573)

A favoured PR device in the late Middle Ages was the ‘royal entry’, when a monarch ostentatiously visited a domestic city or region, leaving a lasting impression. One exponent was Elizabeth I, anxious to encourage national unity in a land riven for centuries by factional interests, and presumably grateful for a summer vacation. Her main ‘Royal Progress’ for 1573 took her around Kent. Starting on July 21st, the outward itinerary ran first through Orpington, Knole, Otford, Birling, Oxenhoath, Kilndown, Bedgebury, Benenden, and Cranbrook. After a foray to Rye, there followed Sissinghurst, Boughton Malherbe, Smarden, Hothfield, Westenhanger, Smeeth, Sandgate, Hythe, and Folkestone, then a five-day break at Dover Castle. She proceeded via Sandwich, Wingham, and Littlebourne to Canterbury, where she remained for 13 days. After Faversham, Sittingbourne, Tunstall, Rochester, Gillingham, Cobham, Sutton-at-Hone, and Dartford, she finished on September 25th back at her birthplace, Greenwich Palace. It placed a financial strain on the hosts, but was immensely popular with her subjects.

The Pythoness of Westwell (1574)

The Pythoness of Westwell (1574)

Mildred Norrington worked as a servant for William Sponer in Westwell. She obviously didn’t get on with her mistress, Alice, whom she accused of keeping the Devil captive in a bottle, then sending him to possess and destroy her. To prove Norrington’s point, the devil inside her put on a show of such diabolical intensity that it would surely have landed her a role in ‘The Exorcist’. Since a charge of witchcraft was then a matter of life and death, the girl was summoned to appear before Thomas Wotton of Boughton Malherbe and fellow justice George Darell of Little Chart. Faced by these two sage old patriarchs at Boughton Place, the girl admitted that she had made it all up with revenge aforethought, and put on a repeat performance to prove that she could do it at will. It cannot have done her employment prospects much good, but her colourful nickname has lived on through the centuries.

The Dover Straits earthquake of 1580

The Dover Straits earthquake of 1580

Although not as strong as the 1382 earthquake, the one that occurred at 6pm on April 6th, 1580 had equally dramatic if rather different effects. Its epicentre was not off the North Foreland but on the coast of France, near Calais. Its impact was spectacular in the English Channel, with freak waves that caused two dozen or more vessels to capsize; one passenger reported that his ship grounded five times on the seabed. The waves demolished a portion of the white cliffs at Dover, bringing down part of the Castle wall with it. Though earthquake damage was worst in Northern France and Flanders, the tremors rendered Saltwood Castle uninhabitable, while in London two children were killed by falling stones. Shakespeare even mentions the earthquake in ‘Romeo and Juliet’. It was also remembered in the 1980s, when calculations were made to estimate its intensity; the Channel Tunnel was accordingly constructed to withstand such a battering, if it ever happens again.

The founding of the Globe Theatre (1599)

The founding of the Globe Theatre (1599)

James Burbage (ca 1531-97) was probably born in Bromley. His trade was carpentry, which later served him well as a theatre-builder. First, however, he cut his teeth as an actor. Possessing all the charms of a top male thespian, he became leader of Leicester’s Men, the foremost troupe in Renaissance theatre. In his forties, he set about building arguably England’s first dedicated theatre since Roman times. ‘The Theatre’ opened in 1576 across the fields in Shoreditch. In the 1590s, Burbage’s legendary actor son Richard began appearing there with the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. Among young Burbage’s friends and colleagues was one William Shakespeare, several of whose early plays must have been performed there. By the time of James’s death, however, the Burbages got embroiled in a legal dispute over the Theatre’s lease. Richard and brother Cuthbert resolved the matter by secretly removing the theatre over Christmas 1598 and rebuilding it in Southwark as The Globe. The rest, as they say, is comedy.

Royal grief at Greenwich (1606)

Royal grief at Greenwich (1606)

The occasion of the last royal birth at Greenwich Palace was also that of its last royal death. In October 1605, immediately before the Gunpowder Plot, it was announced that James I’s wife Anne was pregnant for the ninth time. No expense was spared on the preparations, and the team appointed to deliver the baby included Peter Chamberlen, whose claim to fame was inventing obstetrical forceps. Although the pregnancy went almost to term, the baby, born on June 22nd, struggled for life, and expired the next day after being baptised as Sophia Stuart. The body was buried at Westminster Abbey with a monument artfully designed to look like a crib; a grand tournament at Greenwich that had been organised to celebrate the new arrival was called off. Although still only 32, Queen Anne never had another child. Her brother, Christian IV of Denmark, came to console her a month later.

The great gale of 1624

The great gale of 1624

October 4th, 1624 brought a storm described as “a terrible gale, the like of which has never been seen” – which was really saying something among a nation of seafarers. About 120 vessels had taken shelter in the Downs, normally a safe haven. Ships were torn from their anchorages and tossed around like toys, crashing into each other with calamitous effect, and no hope of rescue. One warship, the Antelope, had her anchor cables severed by a merchant ship, the Dolphin, and was blown onto the Goodwin Sands. Despite losing her rudder and all her masts, she was finally brought to dock at Deptford, but only after the crew watched in horror as the Dolphin went down alongside with all hands. A French warship exploded with the loss of 200 lives, while Admiral Hendriksz’ Dutch flagship foundered. It was perhaps a portent: those two nations had just formed an alliance, and would both be at war with England that century.

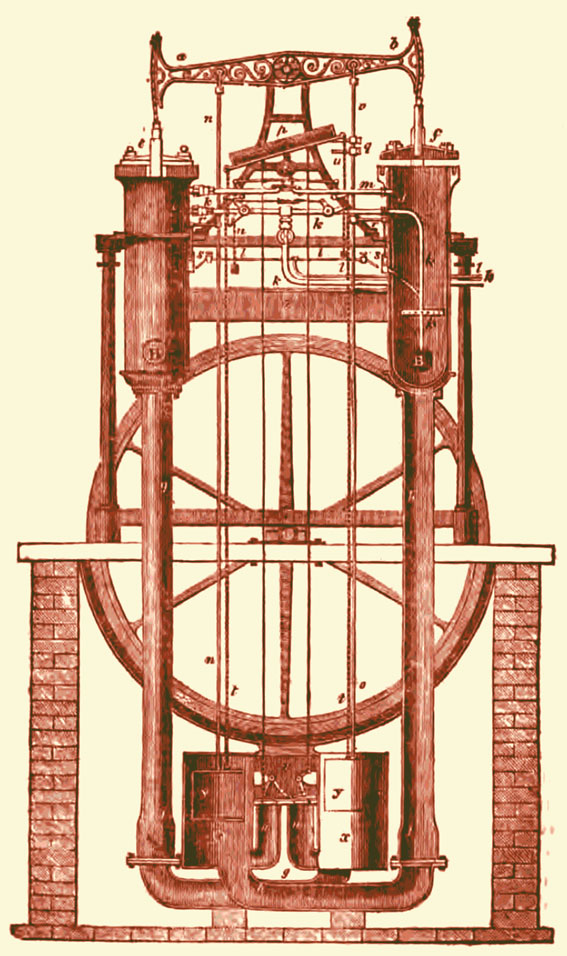

The launch of HMS Sovereign of the Seas (1637)

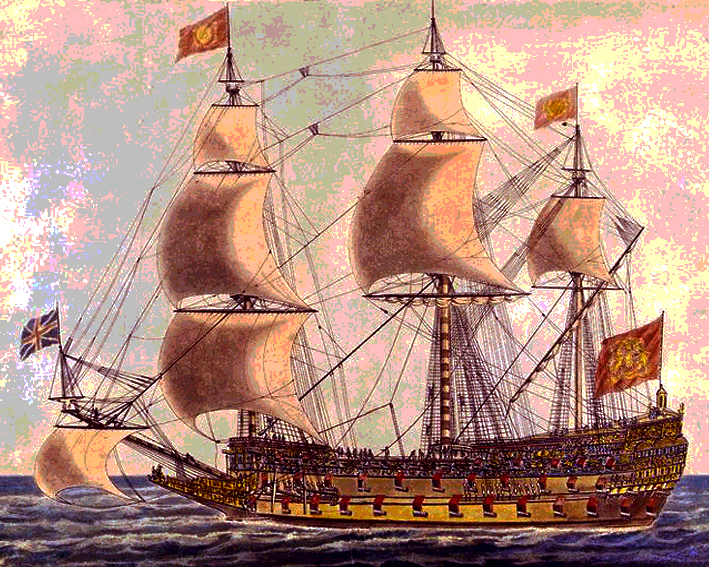

The launch of HMS Sovereign of the Seas (1637)

Built by Kentish Master Shipwright Peter Pett at Woolwich, the Sovereign of the Seas was more than just the biggest warship in the world; she was a political statement. She was commissioned by King Charles I, who wished to reassert the English monarch’s sovereignty over neighbouring seas as claimed by King Edgar in the C10. In 1609, a Dutch jurist, Grotius, had championed the principle of open seas allowing unfettered Dutch access to the English Channel. That demand was rebutted in 1635 by an English book, ‘Mare Clausum’ (‘Closed Sea’), to which Charles lent his weight by having this powerful ship built. He even had an excess of guns added at launch to emphasise the point. The ship – rebuilt in 1660 and renamed Royal Sovereign – fought in major battles both against and alongside the Dutch, but was destroyed by fire at Chatham in 1696. The careless bos’un who’d left a candle untended was flogged and jailed for life.

The Battle of the Downs (1639)

The Battle of the Downs (1639)

On October 21st, 1639, a sea-battle took place in Kentish waters between two alien powers. The antagonists were Spain and Holland, and the warzone the Downs, the safe anchorage off Deal. During the Eighty Years’ War between the Spanish Empire and the emerging Dutch nation, a fleet was sent from La Coruña to reinforce and resupply Spanish troops in Flanders. After a skirmish with Maarten Tromp’s Dutch fleet in the Channel, the Spaniards took refuge in the Downs. The next morning, Tromp attacked with fire-ships as the enemy tried to break out. It turned into a rout. Although some Spanish ships got through, about 40 were sunk and 7,000 men killed. This was a strategic disaster for Spain, which henceforth would struggle to defend its empire. Furthermore, England’s humiliating inability to prevent this blatant breach of its territorial integrity became a factor in the later Anglo-Dutch Wars. Not that the numerous Kentish spectators minded: they joyfully plundered grounded Spanish vessels.

The Kentish Petition of March, 1642

The Kentish Petition of March, 1642

The English Civil War was the outcome of unstoppable force meets immovable object. King Charles I obdurately refused to recognise Parliamentary resistance to his aims, and Parliament obdurately refused to raise taxes if he wouldn’t. There was no desire for regime change; but the nation spiralled downwards as the impasse continued. In March 1642, with hostilities looming, an initiative arose from Maidstone Assizes. Kent was Parliamentarian in outlook, like the rest of the South and East, but had Royalist landowners. The impartial gentry of Kent presented a petition asking the Long Parliament to compromise with the King, particularly by renouncing its claim to controlling the militia. Printed copies of the signed petition were distributed. The demands were moderate, but Parliament reacted with outrage. The Petition’s presenters to Parliament were arrested, its perpetrators were declared delinquents, it was publicly burned by hangmen, and Parliament concocted its own petition with more signatures. By August, the nation was at war with itself.

The Faversham witch trial (1645)

The Faversham witch trial (1645)

Though witches are associated with the Middle Ages, settling scores with an allegation of witchcraft was still commonplace in the C17; and East Kent was a hotspot of indictments. When Thomas Gardiner hurt himself in a fall, Joan Walliford embarrassed him by laughing. He charged her with making it happen by witchcraft. Her friends Joan Cariden, Jane Hott, and Elizabeth Harris were named as accomplices. All either confessed to having had the devil appear to them in the form of a cat or, would you believe, a hedgehog. Their ready admission to such nonsense suggests a good deal of coercion, but it was enough to see them arraigned. Their trial consisted in being dunked in the river. Had they drowned, they would have been held innocent, but the devil helped them stay afloat. On September 29th, three were hanged at Faversham; Harris’s fate is unknown. Fortunately, the scientific revolution would soon be delineating the difference between truth and self-serving superstition.

The Plum Pudding Riot (1647)

The Plum Pudding Riot (1647)

With the first Civil War over and King Charles safely in custody, the Puritan-dominated Parliament was free to throw its ideological weight around. The Puritans’ intolerance did not stop at restricting sports. They even banned Christmas. Popular reaction was predictably hostile, especially in Kent. The Mayor of Canterbury arrived at the marketplace on December 25th to find few traders observing the legal injunction to work normally. When he urged revellers to get to work, he got a surly reaction that turned to pushing and shoving. Someone produced an inflated pig’s bladder, the football of its day. It was a signal for the sort of competitive mass brawl that infuriated the authorities. Before long, it turned to a riot: a metaphorical bloody nose for Puritanism from the rebellious Men of Kent. It signalled an end to the phoney peace, and the start of further hostilities that, by the summer, would turn to mortal conflict.

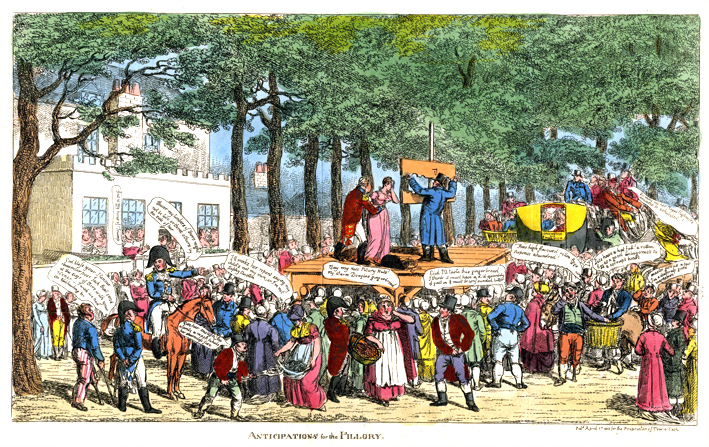

The Battle of Maidstone (1648)

The Battle of Maidstone (1648)

The Kentish rebellion of Spring 1648 went further than football. After sailors mutinied and took over Deal, Sandwich, and Walmer, the Earl of Norwich landed, leading an armed insurrection in Kent and Essex coinciding with a revolt in Wales and invasion from Scotland. His force at Maidstone amounted to 10,000 volunteers; but he made the mistake of sending the majority to defend other towns. On June 1st, he was confronted by a force of 4,000 New Model Army veterans under Sir Thomas Fairfax. The initial combat took place on Penenden Heath, but Fairfax cunningly attacked the town from the south, eventually fighting his way up Gabriel’s Hill and through the town to St Faith’s Church. Havock Square, outside Maidstone Museum, now marks the point where the Royalists made their bloody last stand, although a thousand hid in the chapel before surrendering. Some diehards held out in Essex, but it was curtains for King Charles: he was beheaded in January.

The recapitation of King Charles I (1649)

The recapitation of King Charles I (1649)

A Maidstonian by birth, Thomas Trapham played one of the most peculiar bit-parts in English history: as the man who sewed Charles I’s head back on. Having been licensed by Oxford University to practice as a physician in 1633, his services acquired special value when the bloody Civil War broke out. A Presbyterian, he nailed his colours to the Parliamentarian mast, and was party to the Earl of Essex’s debacle at the Battle of Lostwithiel in 1644. Appointed Cromwell’s surgeon-in-chief, however, he was also at Naseby in 1645, when the New Model Army first impressed itself on history, and the conclusive Battle of Worcester in 1651. After embalming the King’s decapitated body in preparation for burial, he amused some, but infuriated many, by quipping that he had “sewn on the goose’s head”. Somehow he survived the Restoration, plying his trade at Abingdon for two decades. His son Thomas wrote possibly the first manual of tropical diseases. He died in 1683.

The Battle of the Goodwin Sands (1652)

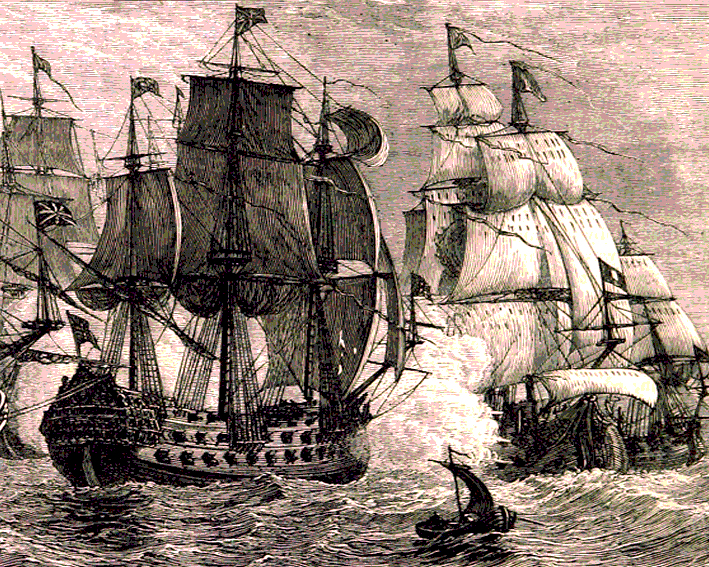

The Battle of the Goodwin Sands (1652)

One of the biggest challenges facing the English Commonwealth under Cromwell was the mercantile strength of the Dutch Republic. The first Navigation Act in 1651 aimed to hamper Dutch shipping, and inevitably stoked tensions. On May 29th, 1652, the great Dutch admiral Maarten Tromp was commanding 40 ships escorting a convoy. He defiantly ignored Cromwell’s decree that foreign ships must respectfully dip their flag when passing through the Channel. The ‘Father of the Royal Navy’ Robert Blake, who was policing the convoy with 25 English ships, fired three warning shots, one of which caused damage to Tromp’s flagship. Tromp returned fire, and a five-hour battle ensued. The Dutch withdrew with the loss of one ship, but the Commonwealth declared war two months later. This First Dutch War started well, when the Dutch fled the Battle of the Kentish Knock in September. However, the Government overconfidently sent warships elsewhere, allowing Tromp to win a major victory off Dungeness in November.

The Maidstone witch trial (1652)

The Maidstone witch trial (1652)

The Faversham witch trial of 1645 exposed the absurdity of charges brought as a means of silencing unwelcome women; but it was not exceptional. A century earlier, Henry VIII had introduced a more liberal Witchcraft Act that redefined the offence as criminal, not religious, and outlawed burning as the punishment. Elizabeth I went further, making hanging the penalty only for a second offence, provided that murder was not involved. Perversely, James I reversed the trend in 1604 by making even injury by witchcraft a capital offence. Witch hunters made a fortune drumming up business for the hangman. On July 30th, 1652, seven witches were tried by Sir Peter Warburton at Maidstone Assizes: Anne Ashby, Mary Browne, Anne Martyn, Anne Wilson, and Mildred Wright of Cranbrook, Mary Reade of Lenham, and Elizabeth Hynes. Ashby proved their collective guilt by reportedly going into ecstasy in court and expanding to a “vast bigness”. All were hanged at once at Penenden Heath, a record.

The Sondes murder (1655)

The Sondes murder (1655)

Saturday, August 7th, 1655 did not start well for widower Sir George Sondes of Lees Court in Sheldwich. He woke at sunrise to find his younger son Freeman at his bedside. The bloodstained boy, 19, reported that he had just murdered his 22-year-old brother George in bed, having premeditatedly beaten his head in with the blunt edge of a meat cleaver and finished him off with a dagger. The dagger was still in his pocket, but he declared, “I have done enough!” and the old man survived. The boy’s motive became a national talking-point. If he hoped to succeed to the family fortune, it was a clumsy way to go about it. There was speculation about devilish possession, and fraternal rivalry over a girl named Anne Delaune. Because Freeman had confessed, however, it was an open-and-shut case at Maidstone Assizes. He was executed at Penenden Heath on August 15th and buried at Bearsted, while old Sondes found himself heirless.

The Indemnity & Oblivion Act (1660)

The Indemnity & Oblivion Act (1660)

Following the Royalists’ crucial defeat at Maidstone in 1648, the position of Clerk of the Court at the King’s trial months later was aptly filled by Andrew Broughton, the town’s Rutland-born mayor. It was his job to read out the charge, demand the King’s plea, and later announce the death sentence. Broughton went on to serve in two Parliaments; but, after Oliver Cromwell died and the monarchy was restored, there came a reckoning. The Indemnity & Oblivion Act pardoned most conspirators, but for 104 “Regicides” there was to be no amnesty. Broughton saw it coming, and fled to Switzerland for the rest of his life. Of the 59 signatories of the King’s death warrant, four others were Kent men: John Dixwell of Dover, Sir Michael Livesey of Eastchurch, James Temple from Rochester, and Sir Hardress Waller of Chartham. The first two likewise fled overseas, while the others’ death sentences were commuted to life imprisonment.

The Long Island land swindle (1661)

The Long Island land swindle (1661)

In 1650, Dorothea Scott (ca 1628-88) from Godmersham, a granddaughter of Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger, inherited Eggarton Manor from her father and married future MP Major Daniel Gotherson. The couple became Quakers, and she wrote a tract called ‘To All that are Unregenerated’ (1661) while preaching to a group called Scott’s Congregation. A New England chancer called Captain Scott approached her, claiming to be a relation, and persuaded her to expend £2,000 (over £200,000 today) on land in Long Island for a new Quaker community. After renaming the area Ashford, he erected three houses there called Scott’s Hall, Egerton (sic), and Braebourne (sic). It was all a swindle: the land was not his to sell. Her husband died, heavily in debt, in 1666. After appealing fruitlessly to Charles II for redress, she remarried locally, sold up, and went to live on a small plot in Long Island. The unregenerated Scott lived out his days in Barbados.

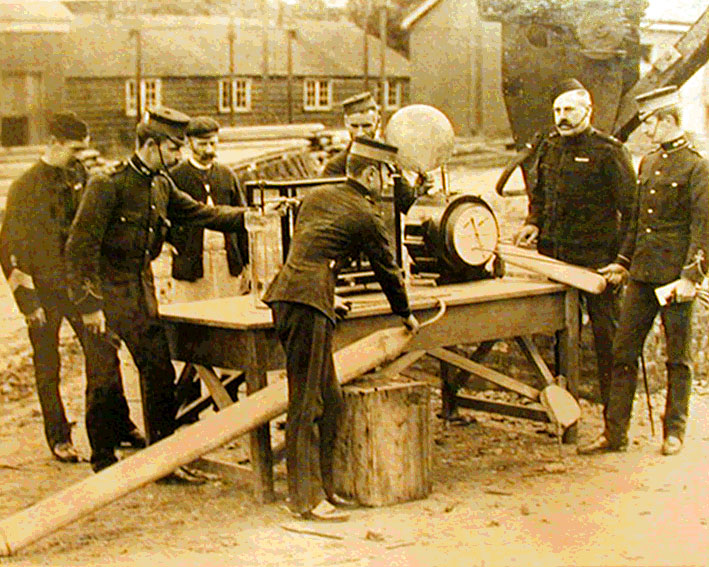

The Raid on the Medway (1667)

The Raid on the Medway (1667)

The Dutch attack on the Royal Navy in the Medway in June 1667 was so expertly executed that it counts as Britain’s own Pearl Harbor. It did not start a war, however, but ended one. The Second Dutch War had been going badly for Britain, which was teetering after suffering the Black Death and the Great Fire of London within the last two years. The Dutch admiral Michiel de Ruyter led a daring mission up the Medway, first capturing the unsuspecting defences at Sheerness and then jumping the ‘Gillingham Chain’ that was supposed to bar entry to Chatham Dockyard. Thirteen major English ships were destroyed at anchor, and the flagship HMS Royal Charles was towed back to Holland as a prize. A month later, Britain sued for peace. De Ruyter is hailed today in Holland as a national hero on a par with Nelson, and the transom of the Royal Charles is displayed proudly in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum.

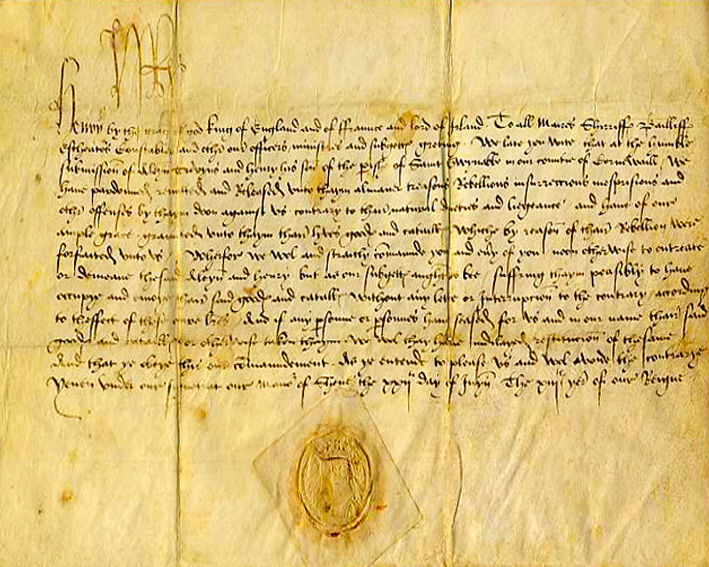

The Secret Treaty of Dover (1670)

The Secret Treaty of Dover (1670)