Coxheath, 1778

Abutilon Kentish Belle

Abutilon Kentish Belle

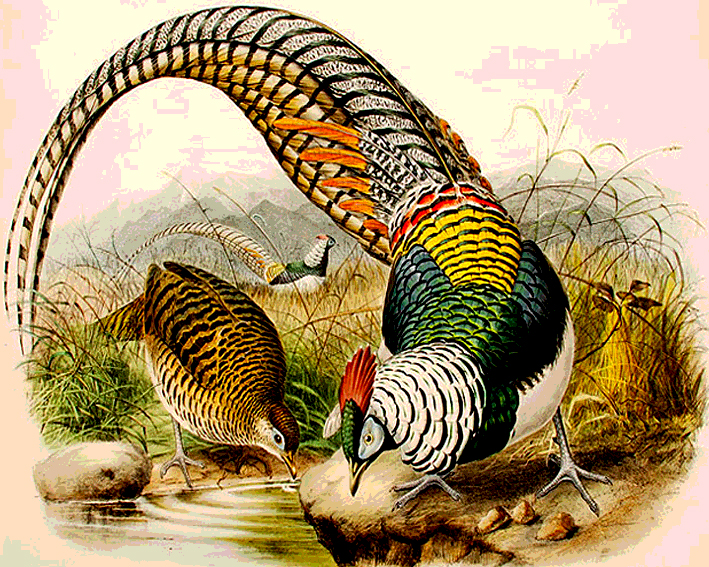

It was the C11 Persian scholar Avicenna who named the Abutilon genus. It meant literally ‘Indian mallow’, which is also the vernacular English name. The fact that its origins are so exotic is a clue to its provenance. Abutilon proliferates across the tropics and subtropics. Some of its 200 or so species, however, were cultivated considerably closer to home. One was the handiwork of Albert V Pike, head gardener of Hever Castle in the 1950s. Because it had attractive bell-shaped flowers and was from Kent, he called it ‘Kentish Belle’. (Geddit?) What makes the species so distinctive is the calyx, the part holding the petals together, which unusually is not green but red, and creates a pleasing contrast with the soft-orange petals. It can grow to the size of a substantial bush in either acid or alkaline soil. There are not many better ways of brightening a garden for months.

Acol

Acol

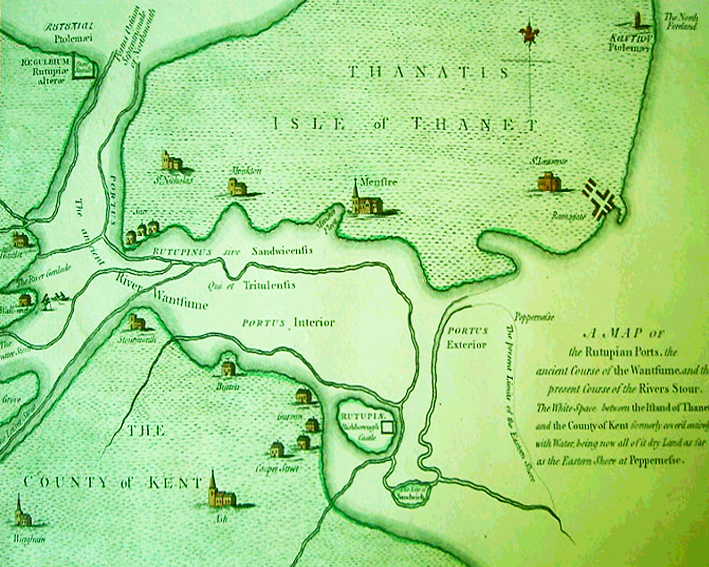

Most contract bridge players know that Britain’s distinctive Acol system of bidding was named after the road in Kilburn, North London, where it was invented. Few however can say why it shares its name with a little-known hamlet in Thanet. The answer is that Colonel Henry Perry Cotton, a Victorian owner of Quex House near Birchington, also possessed a 60-acre estate in Middlesex called Kilburn Woods, which he inherited from his uncle. Around 1880, he developed it and named one of its streets after Acol, formerly known as Acholt, which lies just south of Quex; other streets nearby also bear Kentish names, such as Kingsgate Road, Birchington Road and, not surprisingly, Quex Road. In 1894, both estates would be inherited by his grandson Major Percy Powell Cotton, the famous conservationist after whom the troubled museum is named. By chance, Acol in Kent happens to lie just 11 miles as the crow flies from the village of Bridge.

The Admiral Benbow

The Admiral Benbow

The first six chapters of Robert Louis Stevenson’s ‘Treasure Island’ (1881-2) are set in the Hawkins’ inn, the ‘Admiral Benbow’, named after an extant pub in Cornwall that he evidently visited in 1880. That real pub commemorates John Benbow (1653-1702) from Shropshire, who joined the Royal Navy at 25 and won promotion for his actions against Barbary pirates. After seven years as a merchant seaman, he was appointed superintendent of Chatham Dockyard and then Deptford Dockyard, when he lived at Sayes Court. Meanwhile, he participated repeatedly in the Nine Years’ War with France. Promoted to vice-admiral, he led a squadron in 1702 against a superior French force in the West Indies. When most of his captains refused to fight, he continued the one-sided battle almost unaided until he was crippled by chain shot. His wounds proved fatal, and two of the captains were shot for cowardice; but his cussed determination made him a national hero.

Admiral Hosier’s Ghost

Admiral Hosier’s Ghost

In the 1720s, Britain was not at war with Spain, but knew the Spanish were running gold from Central America to Europe to fund their warlike intentions. In 1726, Admiral Francis Hosier, who came from Deptford and lived at Ranger’s House in Greenwich, was sent with 15 ships to blockade the key port of Puerto Belo in Panama, but was strictly ordered not to capture it, despite his eagerness to do so. The fleet lingered so long at sea that, the following year, nearly all its 5,000 men died of yellow fever. One was Hosier, whom the Admiralty posthumously branded a coward. Twelve years later, with Britain and Spain at war, Admiral Vernon took the port with just six ships, a triumph that led indirectly to the naming of Portobello Road. Poet Richard Glover saw fit to compose a ballad featuring Admiral Hosier’s ghost, who begs Vernon’s men to castigate Robert Walpole’s pusillanimous government for passing the buck.

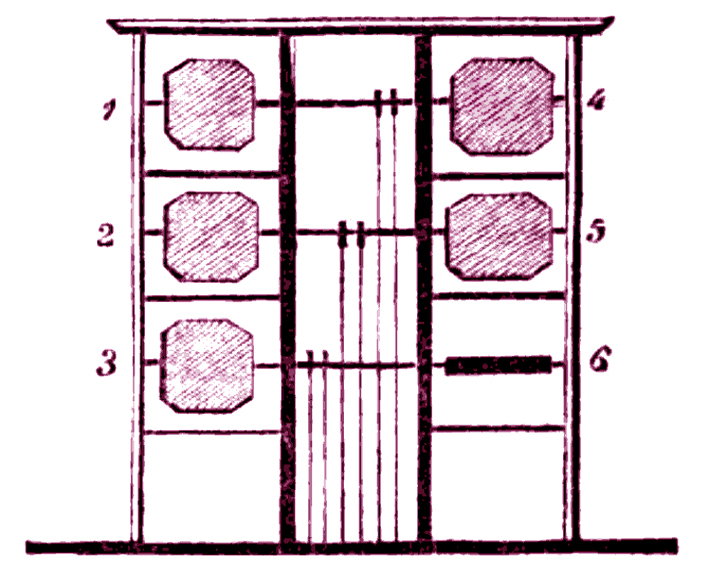

The Admiralty Shutter Telegraphs

The Admiralty Shutter Telegraphs

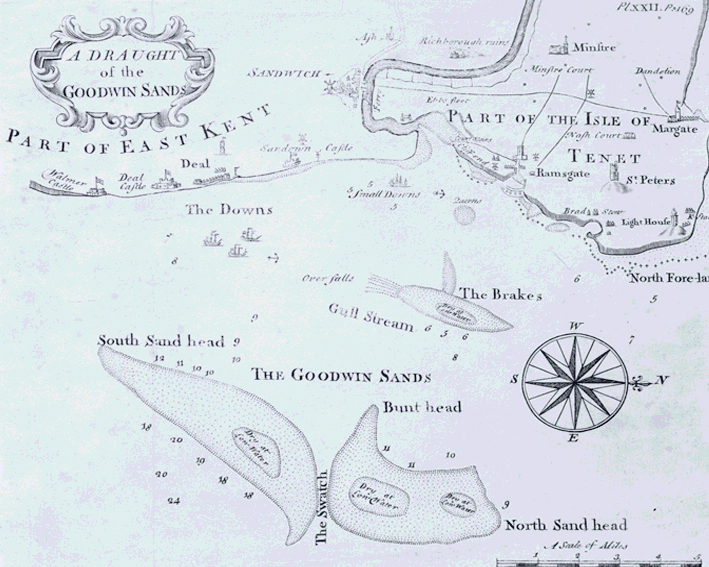

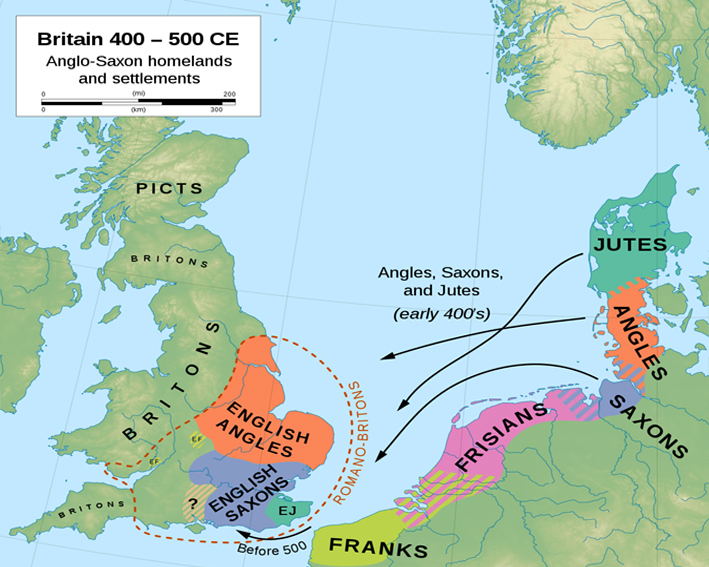

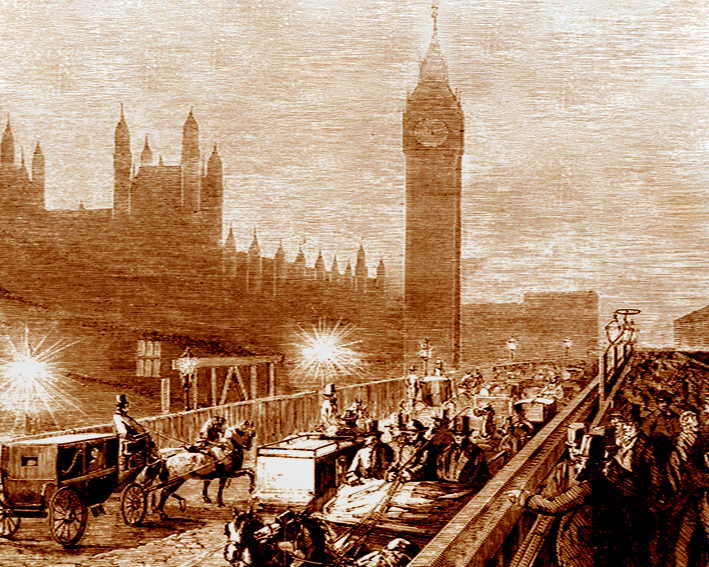

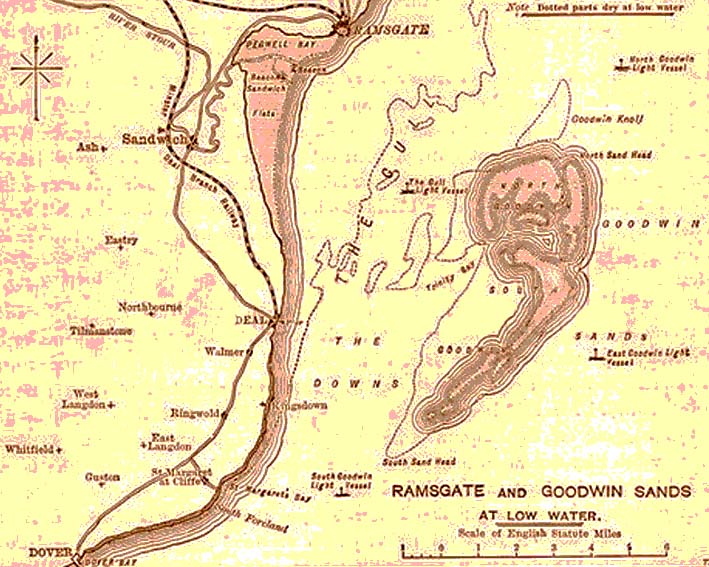

One thing as important in wartime as information is speed of information. At the end of the C19, the swiftest way to send messages was by carrier pigeon. Alarm was caused during the Napoleonic Wars when the French had the idea of sending semaphore messages over long distances via a chain of stations in sight of each other. Each had two mechanical arms on top that, in any particular configuration, indicated a particular letter. The crew of a station noted any message sent to it and recoded it for the benefit of the next. In a great hurry, the British devised their own slicker system, using six shutters. The very first chain, built in 1796, ran from Deal Naval Yard to London via ten intermediate stations, with a branch from Beacon Hill to Sheerness; the Deal station was on the site of the future Timeball Tower. The system worked, but became defunct after Napoleon’s initial defeat in 1814.

‘Adventure in the Hopfields’

‘Adventure in the Hopfields’

The 60-minute flick ‘Adventure in the Hopfields’ (1954) was a classic post-WW2 children’s adventure, with goodies, baddies, and a happy ending. Set during the annual migration of inner-city Londoners to the Wealden hop-gardens, it is based on the Quin family, and specifically their resourceful and incongruously well-spoken young daughter. It must have surprised Kentish folk of the day to see notoriously unruly hop-pickers depicted as the salt of the earth, while the troublemakers are two local ragamuffins called Reilly. Although Goudhurst features prominently in the narrative, the location of the action is the fictional Barden, a portmanteau of Barming and Marden. The dramatic last scene, which (spoiler alert) takes place in a burning windmill, was actually shot in Sussex, as if Kent hadn’t enough attractive mills of its own. It was nevertheless good practice for the young director John Guillermin, who twenty years later struck gold with the star-studded Hollywood epic ‘The Towering Inferno’.

Ale sop

Ale sop

As both the oldest county and a peninsula, it was inevitable that Kent would develop its own unique customs. One such was ‘ale sop’. This was a snack consisting of hot ale served with toast, or sometimes a biscuit, to be dunked in it. The combination sounds strange to modern ears, but there’s a logic to it. In the days before water purification, when the risk of typhoid was ever present, beer was the usual way to consume fluids. In fact, manual workers would generally have many pints a day, albeit less strong stuff than today. Similarly, bread was the most readily available source of nutrition. Warming up the beer and toasting the bread at an open fire was a quick and cheap way of making these staples slightly special. In fact, ale sop may have been considered something of a treat, since it was served to the staff of big Kentish houses on Christmas Day.

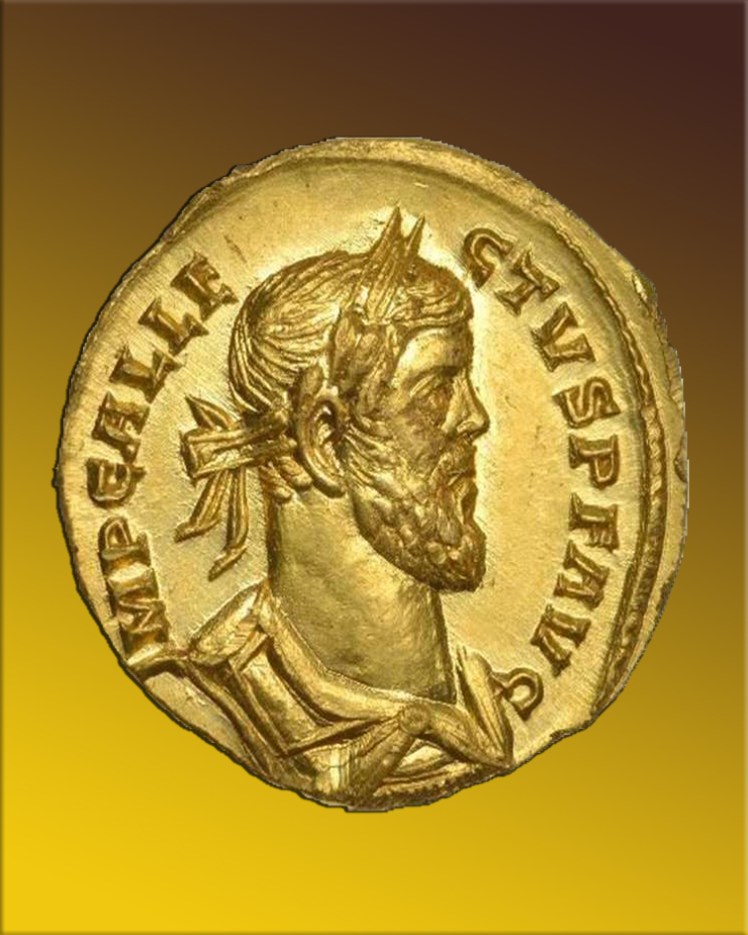

The Allectus coin

The Allectus coin

The anonymous detectorist who unearthed a gold coin at Dover in 2019 was in for a surprise: it sold at auction for half a million pounds, a record for a Roman coin minted in Britain. Curiously, it bore the profile not of an emperor but a short-lived imposter. In the turmoil of the C3, a military commander called Carausius mutinied and declared himself emperor of Britain and North Gaul. When the Empire struck back, his own treasurer Allectus murdered him and took over. Unluckily for the usurper’s usurper, by 296 he found himself up against the formidable Constantius I, father of Constantine the Great. The western Caesar kept the rebel army pinned down in Kent while a second invasion force landed near Southampton. Allectus, racing west to meet the threat, was overwhelmed and slain on the road from Londinium. Ironically, though his reputation was forever tarnished, the coin bearing his name was still in mint condition 1,723 years later.

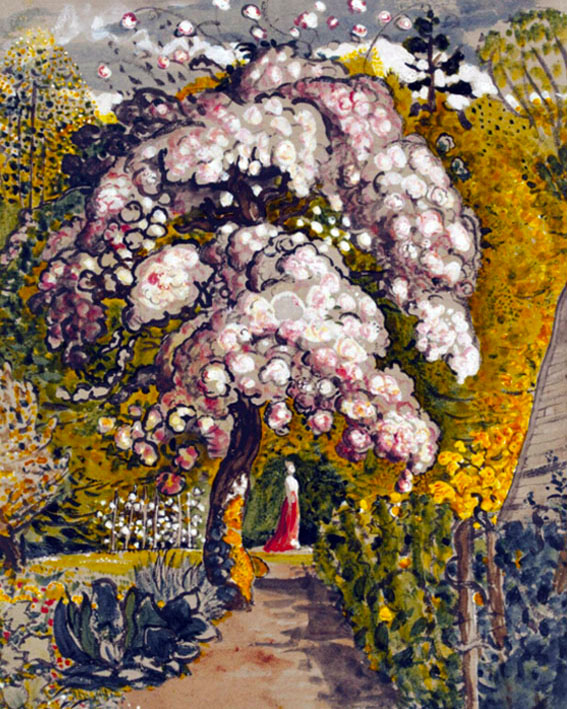

The Ancients

The Ancients

The C19 idea of a ‘brotherhood’ of artists came from the ‘Nazarenes’ of Vienna in 1809. Fifteen years later, the first English brotherhood was formed in Kent. These were the ‘Ancients’, admirers of the great William Blake. All students at the Royal Academy, they were Romantics to a man and seekers after refuge from the age’s commercial spirit. Nevertheless, they were High Tories, which tended to make them a little conventional in their pursuit of spiritual emancipation. Lacking an abandoned monastery to retreat to as the Nazarenes had done, they went to stay for brief periods at Shoreham near Sevenoaks, where Samuel Palmer had a country retreat. The highlight was doubtless the day when the ageing Blake paid them a visit. Though none of the half-dozen or so achieved much while in the brotherhood, some went on to greater things; and they certainly gave the pre-Raphaelites something to shoot at a quarter-century later.

The Andrex Puppies

The Andrex Puppies

In 1942, the St Andrew papermill in Essex started producing the world’s first two-ply hankie, called Andrex, available exclusively through Harrods. In 1955 Bowater, which had been making paper at Northfleet since 1925, bought the brand, and a year later formed a joint venture with the American paper-manufacturer Scott to manufacture tissue. Intent on expanding Andrex’s appeal as an alternative to harsh medicated toilet-papers like Izal, Bowater-Scott’s ad agency devised the idea of a small girl running through her home unravelling a roll of Andrex. The Advertising Standards Authority objected to such wastefulness, so the company substituted a golden Labrador puppy. Over time, this developed into the famous advertising property known in the UK as the Andrex Puppies. The property survives today, albeit under new ownership. Scott bought out Bowater’s interest in 1986, and was itself acquired in 1995 by another American firm, Kimberley-Clark, whose UK headquarters was at Larkfield and then, until recently, at West Malling.

‘Angels One Five’

‘Angels One Five’

“Angels One Five” was RAF parlance indicating a flying altitude of 15,000 feet. It was also the name of a 1952 movie set in 1940 at RAF Neethley, a thinly disguised Biggin Hill. It concerns a young Scottish pilot called Baird, played by John Gregson, who at first is a cold fish but eventually has the chance to prove his mettle. Although only passably entertaining, it is a typically understated testament to the fortitude of the RAF pilots. It also bears witness to Kent’s resilience in the thick of the Battle of Britain. Most of it was shot for convenience in Surrey and Hertforshire, but the action starts with striking footage of Baird’s Hurricane flying across the Medway to the Isle of Grain. The names of operational hot-spots also have a familiar ring: Ashford, Dover, Ramsgate. In a rare moment of sentiment, the diffident Baird summons the courage to invite his would-be girlfriend out to dinner, in cosmopolitan Maidstone.

The archbishop of Canterbury

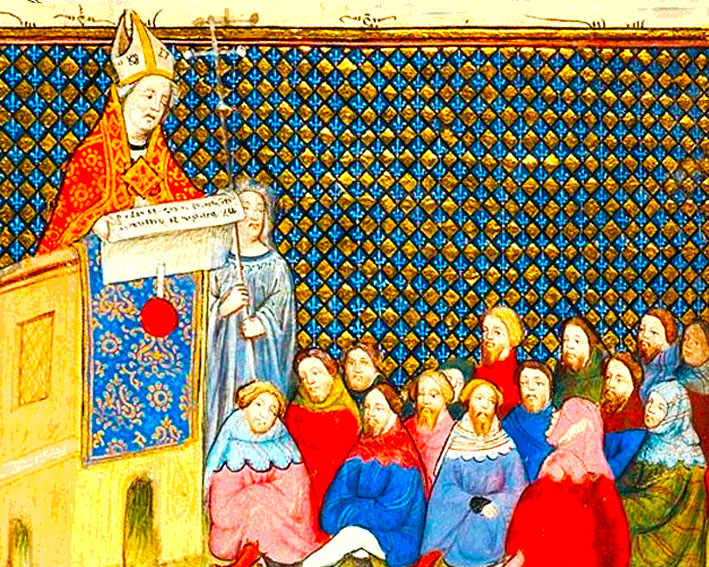

The archbishop of Canterbury

Whatever Pope Gregory I may have intended, his legate Augustine was so swayed by the Kingdom of Kent’s pre-eminence in post-Roman Britain that it was Canterbury, not London or York, that in 597 became the headquarters of the English Church, and its archbishop the eventual leader of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The post has always had uniquely strong Kentish connections. Despite having relinquished his former residences at Charing, Maidstone, Otford, and Sevenoaks, the archbishop still occupies the Old Palace at Canterbury. The bishop of Rochester is his traditional cross-bearer. His four suffragan bishops are those of Dover, Ebbsfleet, Maidstone, and Richborough. As well as chancellor of Canterbury Christchurch University, he is visitor to the University of Kent, the King’s School, Canterbury, and Benenden, Cranbrook, and Sutton Valence Schools. Despite presiding over plummeting congregations, the last four archbishops have retained their political influence, increasingly using it to promote leftist causes. The current incumbent, whose father was Jewish, advocates a multi-faith society.

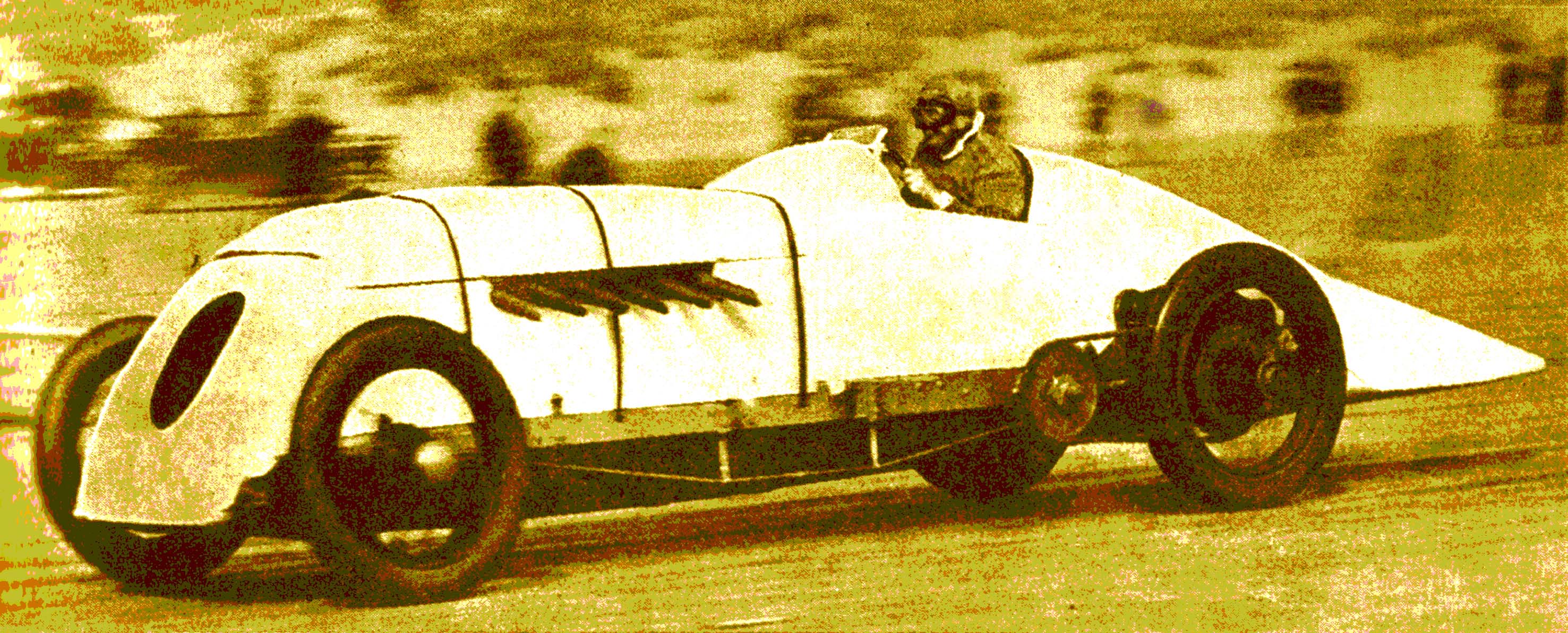

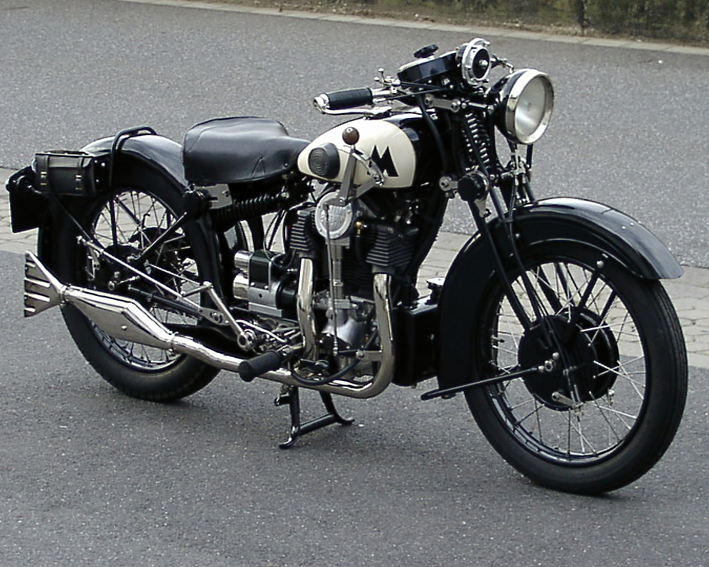

Arnold-Benz

Arnold-Benz

In 1895, William Arnold & Sons was a long-established engineering business in East Peckham, operating also in mills and barges. In 1895, Walter Arnold formed a partnership with Henry Hewetson, who had imported Britain’s first Benz car in 1894. Their Arnold Motor Carriage Company manufactured Benzes under licence using their own motors; they produced a dozen by 1898, as well as some vans. Arnold and Hewetson each travelled in one as a passenger on the 1896 Emancipation Run to celebrate the raising of the general speed limit to 12 mph, although it is doubtful that they drove the whole course from London to Brighton. Ironically, Walter Arnold had been apprehended early that year driving a gasoline-powered locomotive in Brenchley and exceeding the 2 mph limit in Paddock Wood, thereby incurring the world’s first speeding prosecution. An Arnold-Benz, registration number MT 906, was later restored, and survives in the possession of the Arnold family.

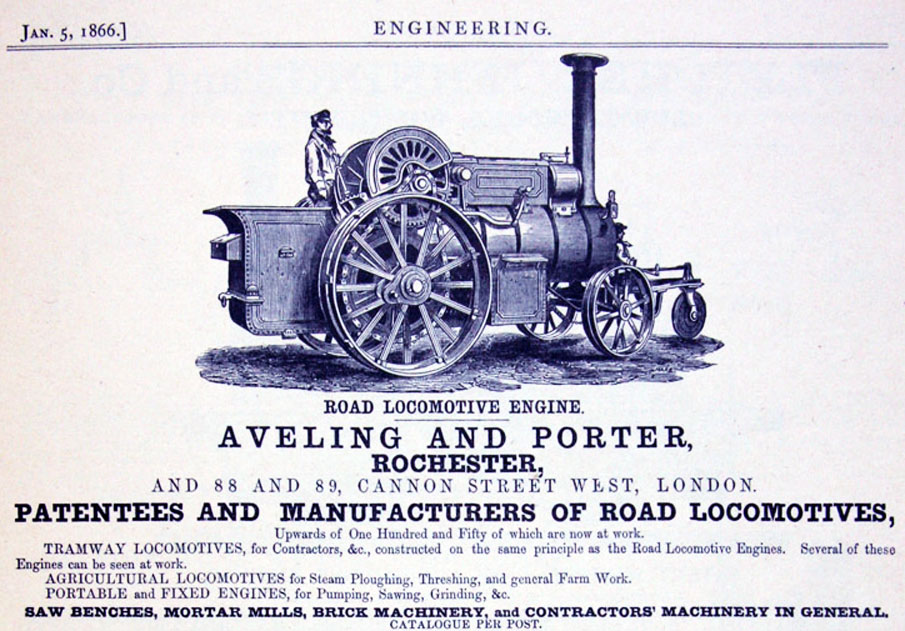

Aveling & Porter

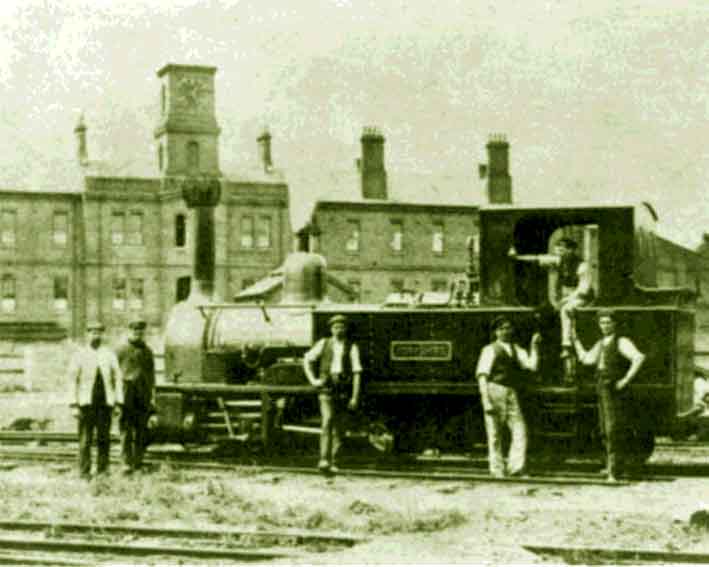

Aveling & Porter

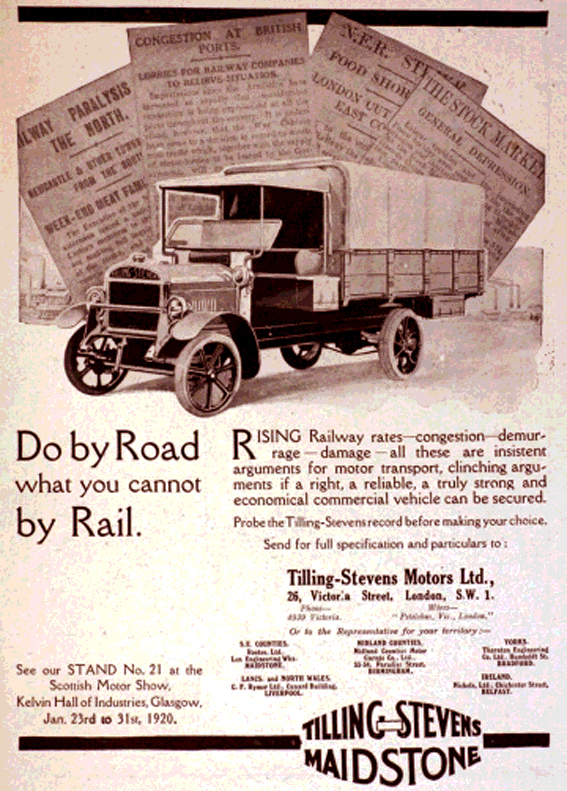

In the 1860s, Kent hosted a revolution in steam locomotion. Steam-engines were then either static or mounted on wheeled frames on rails; agricultural engines had to be drawn on carts by shire-horses. Thomas Aveling, a Rochester engineer, had the idea of connecting the crankshaft to the rear axle, then adding steering. So was born the first self-propelled vehicle needing no tracks. With financier Richard Porter, he developed a company, Aveling & Porter, that led the world in automotion from the Invicta Works beside the Medway at Strood. In 1865, they demonstrated the world’s first steamroller on Military Road in Chatham, Star Hill in Rochester, and Hyde Park, greatly impressing onlookers. Unfortunately, their vehicles’ startling performance provoked the notorious ‘Red Flag’ Act, with its 4mph maximum speed limit. The company eventually constructed over 12,000 engines sporting the Invicta badge. But for internal combustion, Kent might have remained an automotive powerhouse. The Invicta Works was finally demolished in 2010.

Aylesford Paper Mill

Aylesford Paper Mill

Albert Edwin Reed (1846-1920) was a Devonian who made a handsome living from papermaking. His first wholly owned facility in Kent was the fire-damaged Upper Tovil Mill, which he bought in 1894 and revitalised. He specialised in paper for half-tone printing, ideal for newspapers displaying monochrome pictures. This perfectly suited the ambitious Harmsworth Brothers, Lord Northcliffe and Lord Rothermere, proprietors of the ‘Daily Mail’ and the ‘Daily Mirror’ respectively, especially when the latter became the world’s best-selling newspaper. To undercut the competition further, Reed’s sons centralised their several mills at Aylesford in 1922. Within a decade, APM was producing 850,000 miles of paper five feet wide annually, and boasted Europe’s biggest kraft-paper machine. In 1970, however, profitability concerns prompted a takeover of the huge publishing group IPC, heralding a transformation to today’s vast publishing conglomerate, Reed International. Aylesford Newsprint, a Swedish concern, continued papermaking at APM from 1993 to 2015, but the site is now under redevelopment as warehousing.

Aylesford-Swarling culture

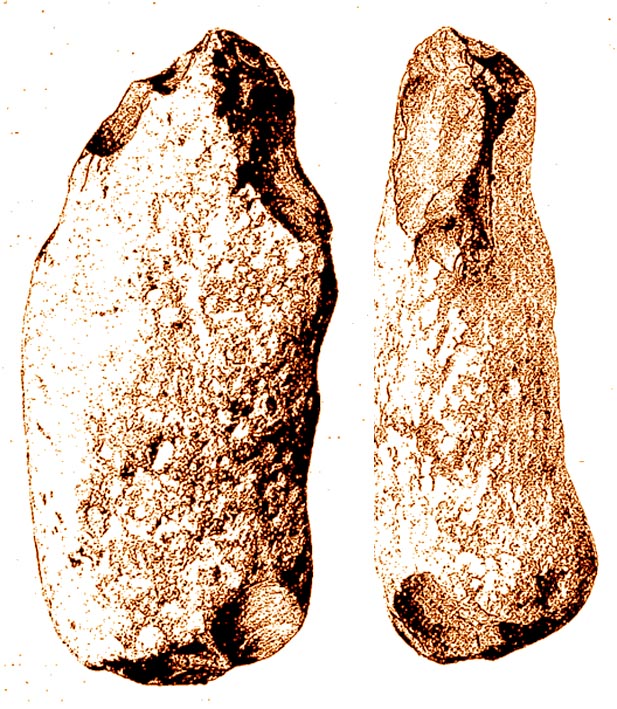

Aylesford-Swarling culture

Two places in Kent, one west of Maidstone and the other south of Canterbury, are united in being the site of ancient cemeteries of special interest to archaeologists. They both contained grave goods particular to the La Tène culture that dominated Europe in the late Iron Age, immediately preceding the Roman Empire. Believed to have been introduced to Britain by the Belgae, a Gallic tribe, they most notably included coinage and wheel-thrown pottery. The design of the latter was distinctly suggestive of Mediterranean influence. There were also bronzes in the Italic style, and even wine amphorae. The Aylesford-Swarling pottery style had spread north of the Thames by the time of the Roman invasion. It goes to show that, with its proximity to the continent of Europe, Kent was a major conduit for cultural diffusion. The Aylesford site, incidentally, was excavated by Sir Arthur Evans, whose next discovery would be the extraordinary Palace of Knossos in Crete.

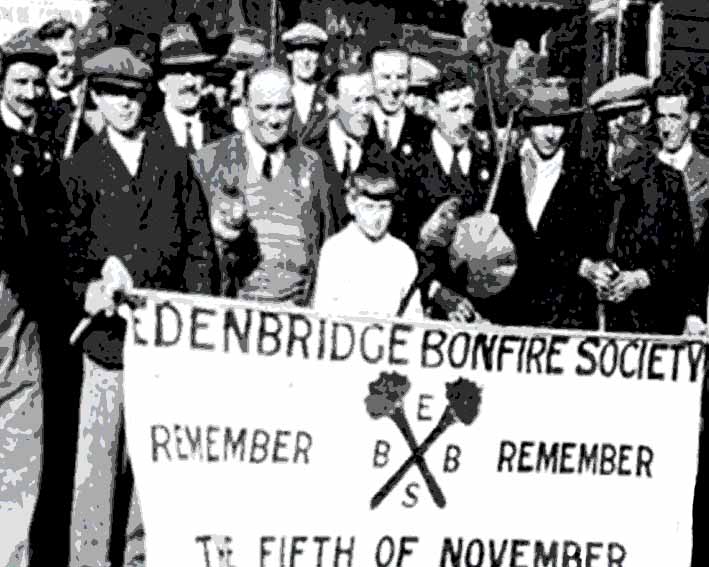

Bank holidays

Bank holidays

Weather permitting, everyone loves bank holidays; but where did they come from? The answer is Lord Avebury, the Lubbock from High Elms who excelled less at sport than science and politics. A banker by trade, he had the idea of creating public holidays when the banks would be closed by law, all transactions being deferred until the following day, and as MP for Maidstone proposed the Bank Holiday Bill. It was enacted in 1871, and the four English bank holidays he’d selected – Easter Monday, Whit Monday, the first Monday in August, and Boxing Day – became part of the culture. Though enthusiasts initially called them ‘St Lubbock’s Days’, some wags claimed that the spring/summer dates coincided with Mondays when his local cricket team was playing. They lasted a century until the Banking & Financial Dealings Act 1971 shifted the May and August holidays to the end of their respective months; the current ‘May Day’ holiday was added by Royal Proclamation in 1978.

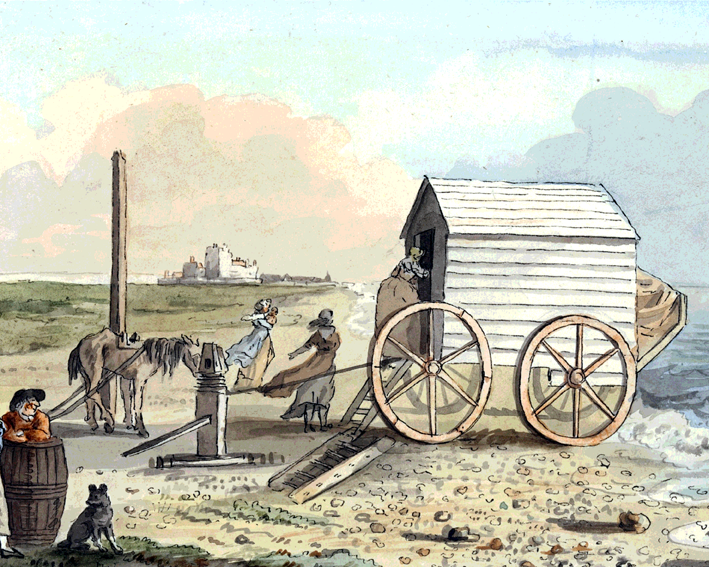

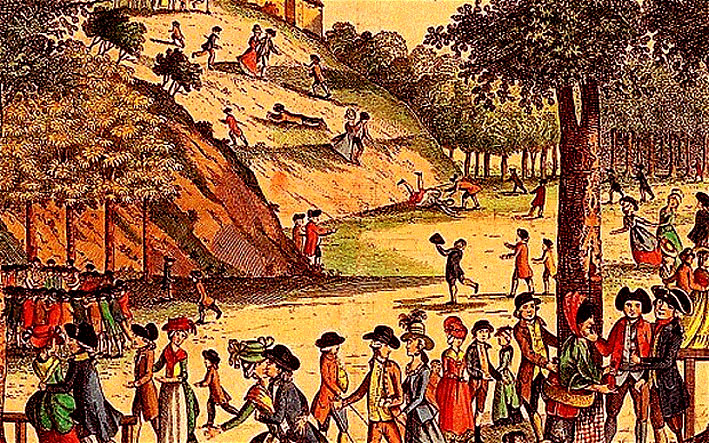

Bathing machines

Bathing machines

Benjamin Beale from Margate is normally said to have invented the bathing machine in 1750, although there is evidence of such a device 15 years earlier. This was simply a means of getting bathers from the beach into the sea without being seen out of their day clothes. It was essentially a box on wheels that would be dragged into the waves by men, or a horse, or even steam power. Bathers would change inside, leaving their clothes on a shelf, and hop into the water on the far side from the beach. The particular innovation by Beale, a propriety-minded Quaker, was the “modesty hood” that could be lowered on the sea side, shielding bathers from the prying eyes of other bathers. Margate, which was then a premier resort, became bathing-machine city. Indeed, when Beale’s booming business was destroyed by a storm in 1767, he was offered the financial support to get it up and running again.

Battenberg Cake

Battenberg Cake

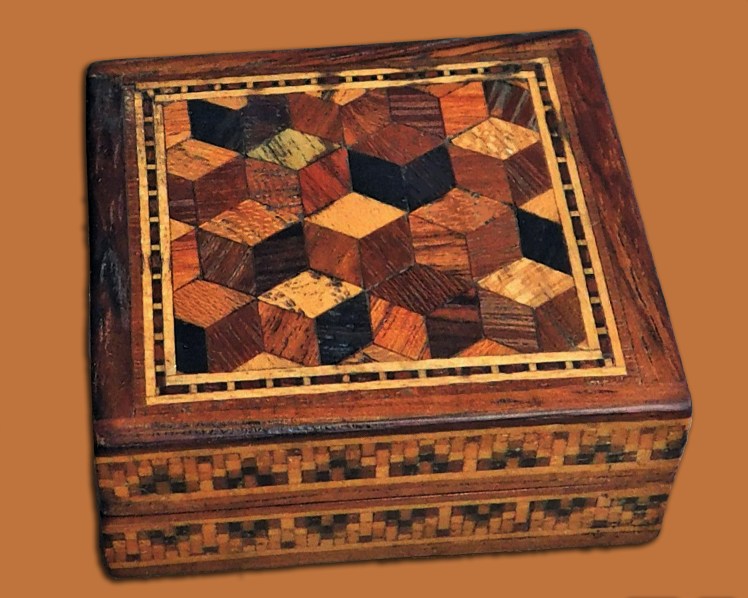

A resident of Brockley, Frederick T Vine was London’s foremost baker at the turn of the C20. Using the ritzy pseudonym Compton Dene, he edited ‘The British Baker & Confectioner’ and wrote numerous illustrated books for the trade, including ‘Biscuits for Bakers’ (1899) and ‘Savoury Pastry’ (1900). Around 1890, Vine described his own ‘Battenburg Cake’ (sic) – a fruit cake. According to legend, the Battenberg Cake familiar today had already been created in 1884 to celebrate the marriage of Queen Victoria’s granddaughter Victoria to Prince Louis of Battenburg, the four panels representing him and his three brothers. Yet nothing resembling it was published before Vine’s 1898 book ‘Saleable Shop Goods’, albeit that his new Battenburg Cake had a nine-square format in alternating red and white. Could it be that Vine simply transferred the name of one of his recipes to another? Curiously, the modern four-panel, pink-and-yellow format was first published elsewhere around the same time, but as a ‘Neapolitaine Roll’.

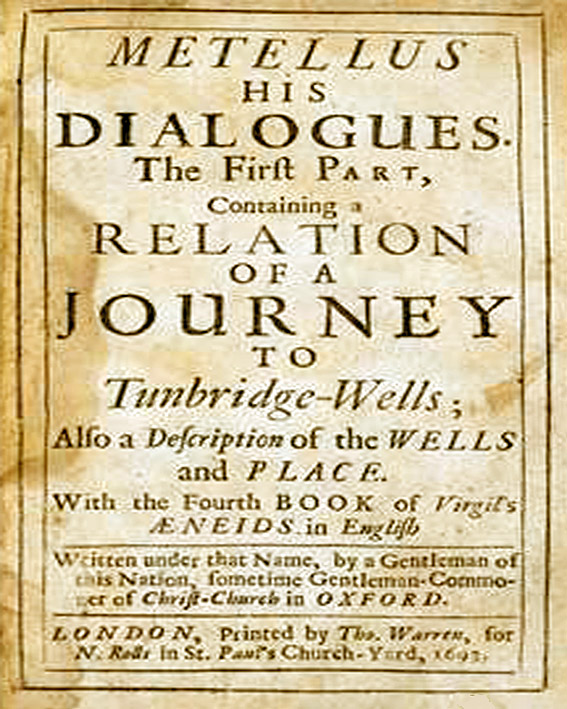

The Beast of Tunbridge Wells

The Beast of Tunbridge Wells

When WW2 was going badly in 1942, minds were distracted by the story of a gigantic apeman in Tunbridge Wells. It supposedly terrified an elderly couple by approaching them from behind as they sat on a bench. Since its coat was bright red, it sounded like a version of the USA’s Sasquatch, or Bigfoot. It might have been forgotten, had not another clutch of sightings been reported seventy years later. ‘The Sun’ carried a story of a walker being confronted in the woods by an 8-foot tall beast with long arms and “demonic” eyes; it roared at him, and he ran off. The stories prompted scorn from local residents, presumably signing themselves ‘Disgusted of Tunbridge Wells’; they put them down to a hoaxster in an outfit. Since a beast like this is unknown to zoology, the best explanation might be that the town is a magnet to tourists, and such tales always add local colour.

Beauty of Kent

Beauty of Kent

In Georgian times, a strain of cooking apple was cultivated that for a century and more went down a storm in England. There were multiple reasons: it was large, it was sweet, it smelt nice, its texture was good, it had a pleasing lemon complexion when cooked, and it was handy for Christmas. As late as 1901, it won a Royal Horticultural Society award. As more science went into breeding apples with looks as well as taste, however, there was trouble. Why? Because this old favourite was not the best looker. While mostly yellow, it had reddish streaks and patches, and was freckly. Recognising the problem, someone – an advertiser, perhaps, or a politician – had the idea of calling it ‘Beauty of Kent’, presumably in the hope that people would be persuaded to disbelieve their own eyes. A name like ‘Deptford Delicious’ might have set less misleading expectations. Although the cultivar fell from favour, Brogdale does still keep a couple of specimens.

The Beauty Show

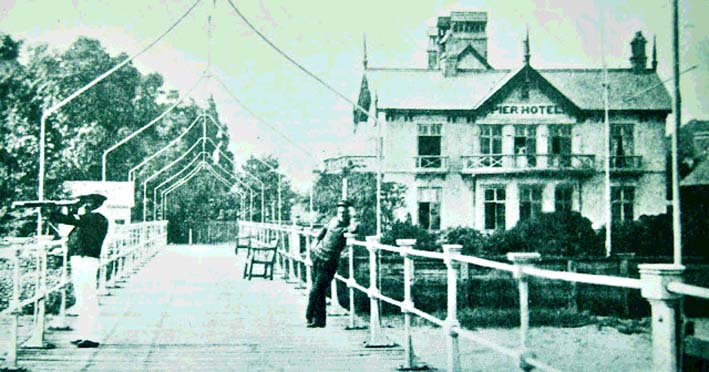

The Beauty Show

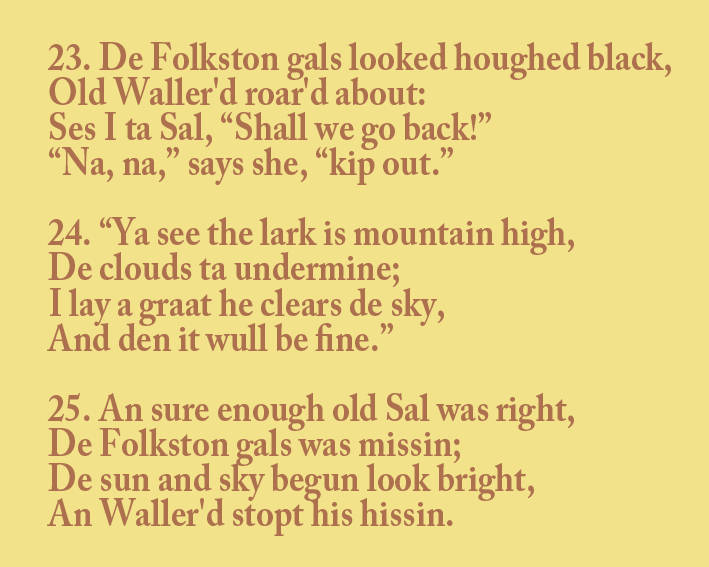

In 1888, an 800-foot pier was built at Folkestone, accommodating an 800-seater pavilion. Saddled with a construction overspend and high running costs, it was a financial failure. That changed in 1907 when a new management team, the Forsyths, took the venue downmarket. In place of highbrow shows, in came all manner of populist entertainments that went down a storm. Most successful of all at the renamed Pier Hippodrome was the innovative ‘Beauty Show’, won by the demure Miss Vogel. So popular was it, especially with women, that a gentlemen’s beauty show was introduced the next month. The event was made an annual international fixture, and the civic ‘beauty contest’ became an institution all over the country. Only after the Women’s Lib protest at the 1970 Miss World contest, one month after Germaine Greer’s ‘The Female Eunuch’ came out, was it regarded as much other than a platform for girls who just wanna have fun.

Bedlam

Bedlam

It’s common knowledge that the word ‘bedlam’ derives from the name of London’s famous lunatic asylum, but few know that the institution now resides in historical Kent. Founded in 1247 near Bishopsgate as the priory of a military order called Our Lady of Bethlehem, its role evolved from alms-collecting to alms-giving, and it was already housing the insane by the late C14. After two of England’s first theatres were built nearby, ‘Bedlam’ was mentioned in numerous dramas, which sealed its reputation for pandemonium. Following its relocation to Moorfields in 1634, it became a lucrative tourist attraction, the more colourful inmates providing a freak-show for a public that regarded mental illness as somehow morally reprehensible. The asylum spent the C19 at Southwark, but was moved again in 1930, this time to Beckenham; the ‘Bethlem Royal Hospital’ is now a well-equipped psychiatric unit. Hollywood’s 1946 horror movie ‘Bedlam’ starred Boris Karloff and Anna Lee, respectively from Dulwich and Ightham.

The Bell Inn revenue inspectors

The Bell Inn revenue inspectors

When smuggling was conducted around Kent’s shores on a scale that would have stretched the Mafia during the Prohibition, it was inevitable that anyone who got in the way of business operations was at serious risk. In the days before motorway bridges, disposal of criminally dead bodies was no easy matter; but plainly there was a deal of resourcefulness. Taverns were always popular resorts for smugglers, one such being the C15 Bell Inn, close to the sea-front at Hythe. When the large inglenook fireplace there was renovated in 1963, the builders uncovered the corpses of two C18 Revenue Officers bricked up behind a wall. They were fully dressed, and their uniforms and boots were in surprisingly good shape. Nothing more is known about them, although customers enjoying a drink or three have reported seeing their ghosts sitting by the fireplace. Presumably the two are ushered out at closing time by the Grey Lady, the ghost of a former owner.

Belmarsh

Belmarsh

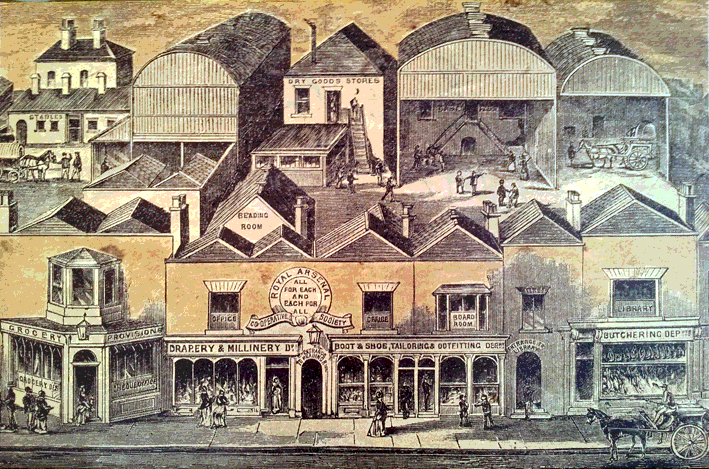

Alongside Woolwich Crown Court on Western Way in Thamesmead, on the historic site of the eastern portion of the Royal Arsenal, stands Britain’s highest-security prison, HMP Belmarsh. Opened in 1991, and now housing around 700 A-category prisoners, it has gained a particular reputation for the harshness of its regime. Indeed, it has been described as Britain’s Guantanamo Bay on account of its use as a centre for detaining terrorists indefinitely without charge. Its recent inmates include Julian Assange, detained for five years until 2024 while contesting US extradition proceedings. Other alumni include such celebrated criminals as Ronnie Biggs and Charles Bronson alongside numerous other high-profile offenders including multiple murderers, serial rapists, and cabinet ministers: Jonathan Aitken, Jeffrey Archer, and Denis MacShane all served time there, the first two for perjury, the last for fraud. Repeatedly criticised for its harsh regime, it was nicknamed Hellmarsh by Archer. In 2009, workmen discovered two wooden trackways there, dating back six millennia.

The Belmarsh Trackways

The Belmarsh Trackways

The marshes on the south bank of the Thames in north-west Kent evidently made an appealing habitat for Stone Age tribes, attracted no doubt by local flora and fauna as food sources. However, getting around became more difficult when the water level started to rise. Two timber trackways excavated in the Somerset Levels during the C20, known as the Post Track and Sweet Track, show they dealt with it in the C39 BC the way we use boardwalks today. In 2009, during construction work beside HMP Belmarsh in Thamesmead, workmen discovered a pair of comparable structures at a depth of 15 feet. Carbon-dated by specialists from Archaeology South-East, they proved to be about as ancient as the Somerset ones, and 700 years older than another, close to North Woolwich, that hitherto had been thought the oldest in the London Basin. To give a better idea of their antiquity: they were constructed more than a millennium before Egypt’s oldest paved road.

Benenden School

Benenden School

After the Norman Conquest, the area where Benenden School now stands was owned by Bishop Odo. In 1216, John Hemsted built a house there that Elizabeth I later visited. In 1718, Hemsted Park was purchased by Admiral Sir John Norris, whose grandson lived there with his wife, the notorious courtesan Kitty Fisher. Lord Cranbrook replaced the old house in 1860 with a dynamic new building that Lord Rothermere rendered less ostentatious in 1912. Eleven years later, three Wycombe Abbey teachers – Christine Sheldon, Anne Hindle, and Kathleen Bird – left to start a new boarding-school for upper-class girls there. ‘Benenden’ rapidly built and maintained a reputation as one of Britain’s most prestigious girls’ schools, and unlike its traditional rival Roedean has not sacrificed its quintessentially English character. Its most high-profile alumna is Princess Anne, who was friends there with Jordanian princess Alia bint Hussein; but its most influential is probably the former spymaster, Lady Manningham-Buller.

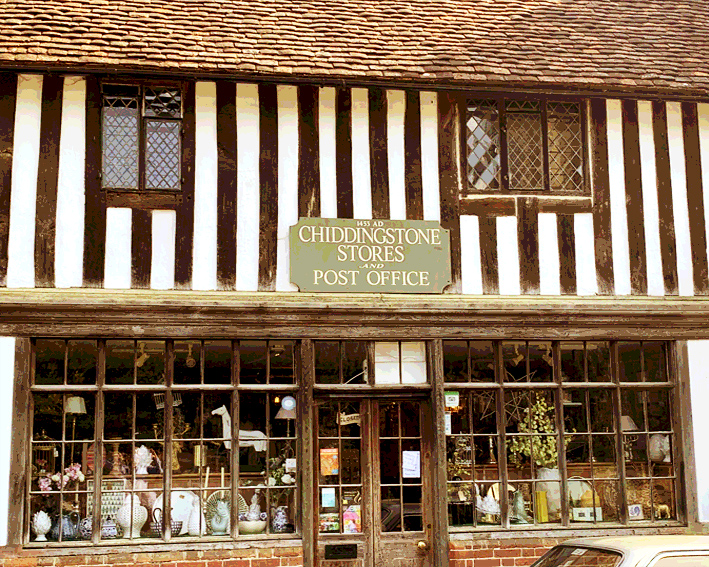

Bethersden marble

Bethersden marble

Geologically, Bethersden marble shouldn’t be called ‘marble’ – because it’s not metamorphic – and it doesn’t necessarily come from Bethersden: lesser deposits were also found in Sussex. Yet the material itself is as distinctive as its name. It was formed from bands of freshwater limestone left behind in the Weald when the waters receded. Its distinctive appearance is derived from the calcified remains of freshwater snails, giving it one of its more colourful alternative names: winklestone. As it can polish up to an attractive shiny appearance, it is has been used in architecture and building since medieval times in the same way as actual marble, with such diverse applications as the pavement outside the Red Lion in Lenham, the exterior of the Dering Arms in Pluckley, and the Archbishop’s chair at Canterbury Cathedral. Although Bethersden marble is scarcely mined now, relics of quarrying remain in the form of ponds, some now used as fisheries, dotted around the Weald.

Betsey Trotwood

Betsey Trotwood

A formative influence on David Copperfield in Dickens’ eponymous novel is Betsey Trotwood, his resolutely misandrist great-aunt who paradoxically takes him under her wing and procures him a good education in Canterbury. So sharply delineated is her personality that she has been played in movie adaptations by such stars as Edith Evans, Maggie Smith, and Tilda Swinton. One good reason why she seems so human – apart from Dickens’ enormous talent for characterisation – is the fact that she was based on an actual woman of his acquaintance. That woman was Mary Pearson Strong, and she lived in the cottage in Victoria Parade, Broadstairs that is now home to the Dickens House Museum. Curiously, when an American businessman was applying for a post office franchise in Ohio in 1866, he was just reading ‘David Copperfield’, and successfully applied for the name ‘Trotwood’ – the only municipality in the world bearing that name. Closer to home, a traditional Victorian pub in Clerkenwell commemorates her.

Bewl Water

Bewl Water

Only half a century ago, Bewl Water was a valley occupied by the River Bewl. By 1975 it had been converted to a reservoir containing 7 billion gallons of water, making it the biggest lake in the South-East. The intention was to provide a dependable water source, diverting water from the River Medway whenever volumes reached a set level. Although its purpose was purely functional, its construction has had the unintended consequence of providing a useful artificial addition to nature. As well as looking quite scenic in places, it has become home to a plethora of animal species, especially birds. Like most large bodies of water, it is also a magnet to humans, providing not only angling but also numerous water sports and other leisure activities. Proposals to increase the offtake from the Medway in view of Kent’s now steepling population have however met with opposition because of the risk of environmental degradation.

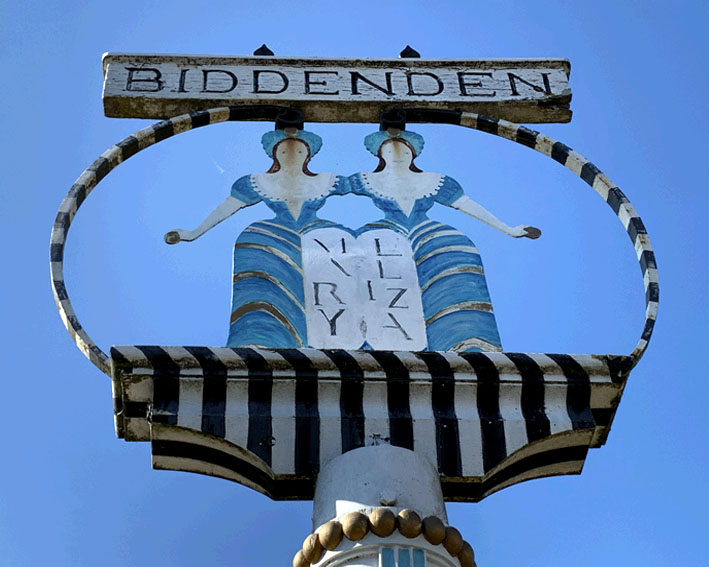

The Biddenden Maids

The Biddenden Maids

As Lady Godiva is to Coventry, so the Maids are to Biddenden. According to the legend, they were C11 Siamese twins who bequeathed to the village the ‘Bread & Cheese Lands’ whose revenue funded a ‘dole’ of victuals to the needy each Easter. The tradition continues today, lavishly funded by the sale of the Lands for housing. The Maids appear on both the village crest and the Biddenden ‘cakes’ handed out or sold to visitors. These biscuits are barely edible, being baked in batches every few years to a hardness that makes them durable souvenirs of the Maids’ generosity. The two were given suspiciously modern names and a back-story in Victorian times; but it’s hard to escape the conclusion that even the Siamese twins yarn was an invention. Most likely it was a traditional image of two loving sisters baked into the biscuit – like the cow on a malted milk – which gave some joker the idea.

Bigbury Camp

Bigbury Camp

In Howfield Wood, east of Chartham Hatch, is an Iron-Age fort that, dating to the middle of the C4 BC, is uniquely old in East Kent. Bigbury Camp, formerly known as Bigberry, covers 26 acres and, as is typical of a so-called univallate hillfort, is surrounded by defences following the natural contours of the terrain. This Celtic camp had two entrances, to the east and west, and a secondary area at its northern end that was perhaps an enclosure for livestock. Archaeological finds include a large hearth, a Celtic slave-chain, and Aylesford-Swarling pottery. Bigbury was quite possibly attacked by the 7th Legion during Julius Caesar’s invasion of 54 BC. It is even conceivable that, having been expelled, the Celts withdrew to the east and built a new stronghold that eventually became Canterbury. The site, which is crossed by the North Downs Way and Pilgrims’ Way, is now under the management of Kent Wildlife Trust.

Biggin Hill

Biggin Hill

Biggin Hill is one of the most romantic names in aviation history. It was used as a wireless-testing site in WW1 until, in 1917, the Royal Flying Corps moved its headquarters there from Dartford. The airfield was a prominent RAF base in the Battle of Britain, its fighters claiming 1,400 enemy aircraft at the cost of 453 personnel. A priority target for the Luftwaffe, it underwent 12 raids in five months. After WW2, it became a joint military and civilian airport. RAF operations stopped in 1958, although one section is still military. Despite lying well outside the urban sprawl, it was sold to the London Borough of Bromley in 1974. The council, as freeholder, secured a court ruling in 2001 barring flights with paying passengers. The famous Biggin Hill International Air Fair took place from 1963 to 2009, but relaunched in 2014 as a smaller Festival. The museum and chapel can still be visited.

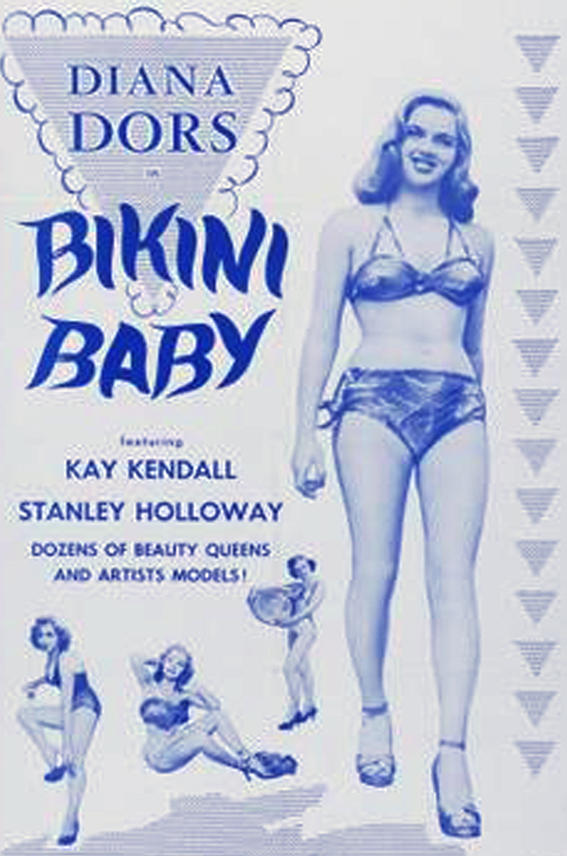

‘Bikini Baby’

‘Bikini Baby’

Inspired by a Miss Kent beauty contest at Folkestone’s Lea’s Cliff Hall, where he was a judge, director Frank Launder devised a movie under the provisional name ‘Beauty Queen’. It looked promising, with talent like Dennis Price, Stanley Holloway, Dora Bryan, George Cole, and Trevor Howard on board. The lead role was awarded to Pauline Stroud from Tunbridge Wells, who was cast ahead of future superstar Audrey Hepburn. A bevy of beauties came to Folkestone for the shoot in 1951, including a young Joan Collins. Possibly sensing a turkey, however, the producers sexed up the title to ‘Lady Godiva Rides Again’; and, after the movie arrived in the USA, it was re-released under the name ‘Bikini Baby’, with the buxom Diana Dors given star billing, even though she only appeared in half the film. The movie was soon forgotten, at least until 1955, when one of the extras, Ruth Ellis, became the last woman to be hanged in Britain.

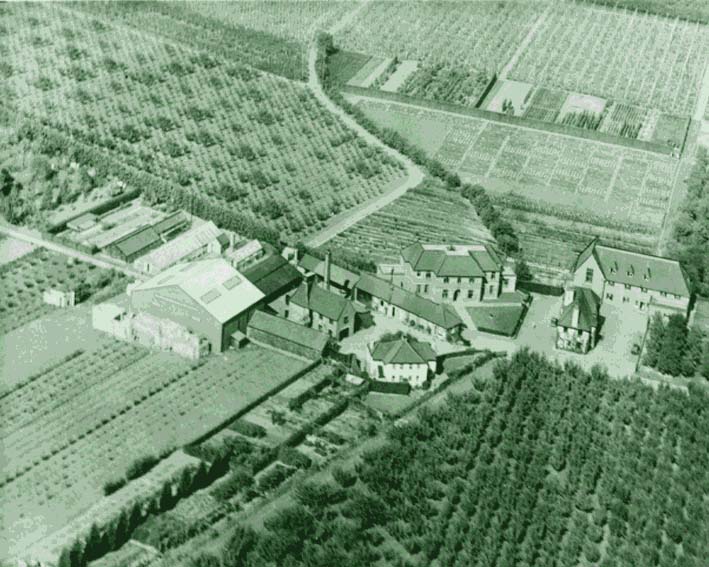

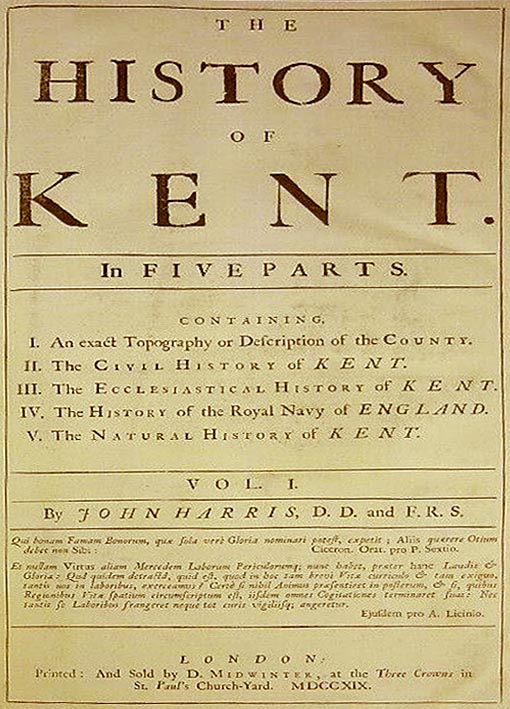

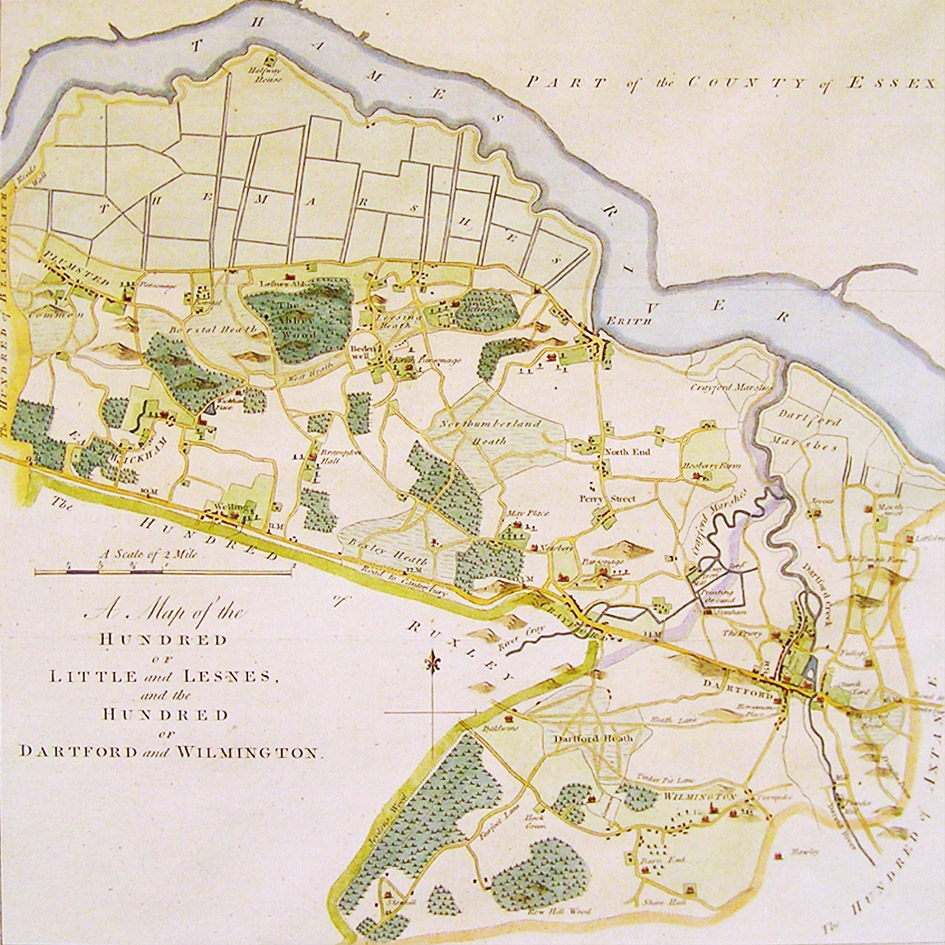

Bird’s-eye views

Bird’s-eye views

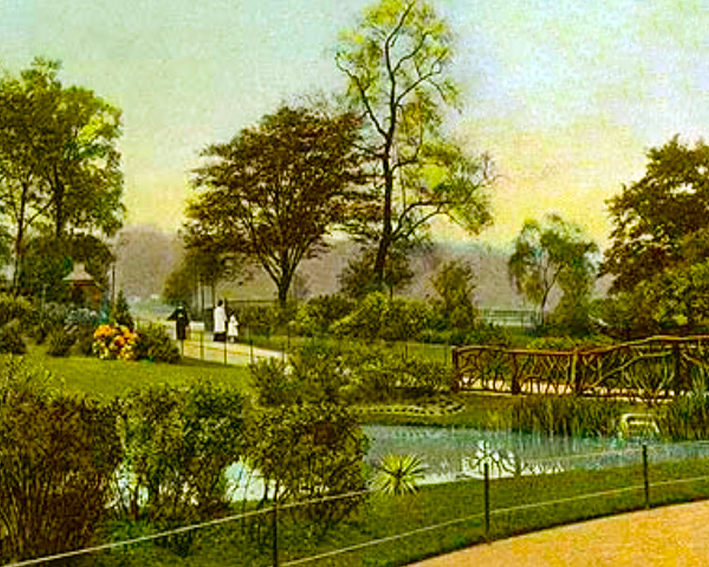

In the early C18, a pair of Dutchmen, artist Leonard Knijff and engraver Jan Kip, had a brainwave. They would sell English stately-homeowners the idea of mapping out their estate in painstaking detail, and then producing an intricately detailed image of the house and its surrounds as if seen from 200 feet up a quarter-mile away, long before hot-air balloons. They created 79 of these ‘bird’s-eye views’ that appeared in the first volume of ‘Britannia Illustrata’ in 1708, the Kent subjects being Knole, Fairlawne, and Doddington. Kip single-handedly created 17 more for Dr John Harris’s incomplete ‘History of Kent’ (1719), of which some were re-used in ‘Britannia Illustrata’ volume 2 (1724). Academic study has shown they were not entirely accurate, but they do include some interesting details of everyday country life, and provide a valuable record of the layout of formal gardens in the era before Capability Brown came along with his new broom.

Black-eyed Susan

Black-eyed Susan

In 1720, John Gay of ‘The Beggars’ Opera’ fame wrote a ballad called ‘Black-Eyed Susan’ that became a lasting hit. The eponymous young woman Susan goes to find her “sweet William” on his warship in the Downs, just as he is about to set off around the world. He seeks to assure her of his undying love, culminating in the affirmation that yes, he will have a girl in every port, but she will always be Susan: the diamonds of India will be her eyes, the winds of Africa her breath, and its ivory her skin. So touching was it that the song was still very popular more than a century later, and a version has been recorded even this century. As familiar in America as it was in Britain, the song’s name was adopted as the appellation of Rudbeckia hirta, a flower native to America whose dark centre suggested its now more familiar name.

Blackwall Tunnel

Blackwall Tunnel

Even before Whitehall annexed north-west Kent, a London MP had suggested the economic value of a cross-Thames road link between the East End and the Greenwich peninsula. One of London County Council’s first big infrastructure projects was a two-lane tunnel connecting Poplar with today’s A102. It got its name not from its internal appearance but the hamlet of Blackwall at its northern end, itself named after a stretch of river wall. Designed by Sir Alexander Binnie and completed in 1897, the tunnel had several bends, a ceiling that was in parts too low, and limited capacity that caused a chronic bottleneck. This problem was partially addressed by 1967, when a new, second tunnel doubled the number of lanes in each direction. Nevertheless, the problem of congestion remained, a fact the IRA sought to exploit in 1979 when it blew up an adjacent gas holder. Relief may finally be provided by a new tunnel running from North Greenwich to Silvertown.

Bluebeard the Hermit

Bluebeard the Hermit

Contrary to expectation, Bluebeard the Hermit was not a savage pirate who hung up his cutlass to go into social isolation. In truth, we know little about him, but he is a footnote in Kent history because of his role in Jack Cade’s rebellion in 1450. The known facts are that he was a fuller by the name of Thomas Cheyny, he became a ringleader of the rebels in Canterbury, and he may even have initiated the revolt. His nickname simply followed the practice among rebels of giving themselves counterfeit names as they went about fomenting rebellion; the hermit was a favourite disguise. After the collapse of the revolt, ‘Bluebeard’ was summarily executed. It caused such public unrest that the Sheriffs of London, ordered to take the head back to Canterbury for display on the Westgate, were in fear of their lives, and demanded recompense. The head did make it home; but Bluebeard’s quarters adorned four other towns.

The Blue Bell Hill ghost

The Blue Bell Hill ghost

Tales of a ghost on Blue Bell Hill between Maidstone and Chatham are thought to derive from a tragic accident in 1965. While returning from her hen night on the eve of her wedding, 22-year-old Susan Browne was killed with two friends after losing control of her Ford Cortina. Few locals didn’t hear the story, and most paid close attention when different drivers, always male, started reporting supernatural encounters with a female road user. It might be an eerie pedestrian who’d get mowed down but leave no trace, or else a hitchhiker who’d disappear from the back seat. Soon everyone using that road was looking out for paranormal activity. In retrospect, it’s easy to attribute those reports to either over-fertile imaginations or simple hoaxes; and the A229 is too slick a road nowadays to lend credence to ghost stories. Try walking at dusk along the single-track Old Chatham Road that passes underneath, however, and it’s a different story.

Bomb Alley

Bomb Alley

With WW2 effectively lost and no hope of beating the Allies to the atomic bomb, Hitler put his faith on so-called ‘retribution weapons’. Three came to fruition: the V-1 flying bomb or ‘doodlebug’; the V-2 rocket with its 2,200-pound warhead; and the V-3 supergun, firing shells 100 miles. Thanks to RAF bombers, the V-3 never became operational, but 9,521 V-1s and 1,358 V-2s were fired across Kent. The V-2s either reached London or landed in less inhabited areas, but many V-1s fell short, including the first (at Swanscombe on June 13th, 1944) and the last (at Orpington on March 27th, 1945). Kentish people grew to dread the familiar overhead rumble, which would fall silent seconds before the 1,875-pound warhead struck. The RAF did its best to shoot them down or tip them off course; but 1,444 V-1s still came down in Kent, costing 200 lives. They continued to be a worry until all launch sites were bombed or captured.

‘Boom, Oo, Yatta-ta-ta’

‘Boom, Oo, Yatta-ta-ta’

Richard Hills (1926-96) and Sidney Green (1928-99) were both school captains of Haberdashers’ Askes in New Cross, two years apart. Hills played rugby for Kent and became a Cambridge-educated teacher, while Green tried various jobs before they teamed up in Forest Hill to write comedy. Their success with radio and TV comic Dave King opened doors with the likes of Anthony Newley and Frankie Howerd; but their apogee was Morecambe & Wise’s ATV series ‘Two of a Kind’ (1961-8), in which they adeptly enhanced the pair’s spontaneous and often visual humour. They first appeared onscreen as ‘Sid & Dick’ to back Eric & Ernie’s hapless crooning with their deadpan “boom, oo, yatta-ta-ta”, later released as a single. The partnership did not survive Morecambe’s first heart attack in 1968: whilst he recovered to enjoy huge popularity on BBC TV, Hills’ & Green‘s careers languished in America. They ended up writing for Cannon & Ball in the 1980s.

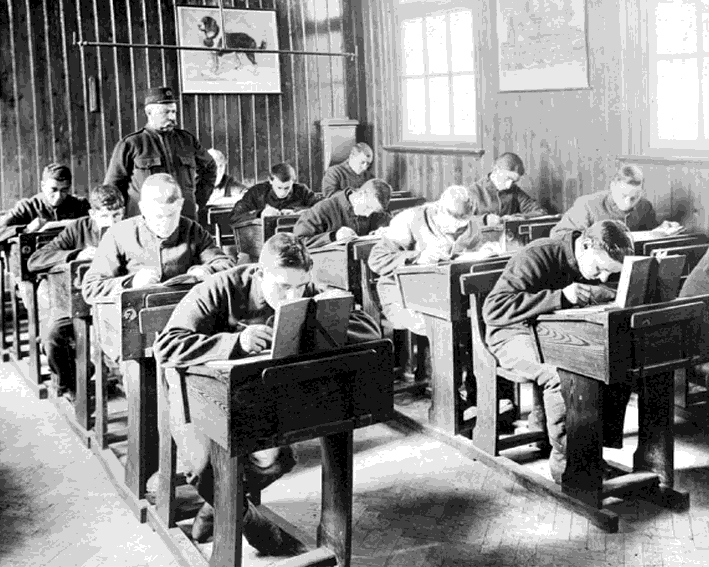

Borstal

Borstal

The borstal project was a triumph of idealism over realism. Its intentions were honourable: it sought to keep young males out of adult prisons so that they would not be groomed for a life of crime. The location chosen for the first institution in 1902 was the village of Borstal, near Rochester, which had once been a beauty spot. The emphasis was on reforming boys through education and discipline, rather than punishment; caning, for example, was forbidden, and birching rare. It worked well enough to be rolled out across the country, retaining the borstal name. Brendan Behan wrote a rose-tinted account of his time in one in the 1940s, when befriending Protestant boys moderated his Irish Republican sympathies. In 1979, however, the movie ‘Scum’ gave a stomach-churning picture of what borstals had become: a playground for psychopaths. In 1982, they were replaced by youth custody centres; yet the Kentish village’s name still lives on in India’s surviving borstal schools.

Botany Bay, sha la la

Botany Bay, sha la la

Everyone who was in France in the spring of 1976 will recall the big teen-flick hit of the year, ‘A Nous Les Petites Anglaises’ (‘The Little English Girls Are Ours’). This was a light-hearted romp involving two adolescent French schoolboys who, having failed their English exams, are urged to go on a summer vacation in England to improve their language skills. They like the idea because they have heard that English girls are easy. It turns out that they are able to have more fun with French ones, partying and dancing le Rock. What makes the movie an interesting historical document is that it was filmed primarily at Ramsgate, with additional beach scenes just north of Broadstairs at Kingsgate Bay and Botany Bay. The American soundtrack composer, Mort Shuman, even wrote a rock ‘n’ roll number with the unlikely title ‘Ramsgate Rock’, not to mention the film’s catchy theme tune, ‘Botany Bay’.

The Bouncing Bomb

The Bouncing Bomb

Although the Bouncing Bomb counts among the most celebrated of innovations in weaponry, its Kentish connections are less well known. Its inventor Barnes Wallace went to school in New Cross, began work at Blackheath, and during the War worked extensively at Fort Halstead, a weapons research facility near Sevenoaks. Although the concept of bouncing a heavy object across the surface of a body of water was initially tested at Chesil Beach in Dorset, the first trial using a wood-encased bomb was undertaken off Reculver on April 13th, 1943; and, one month later, a live bomb was exploded five miles off Broadstairs by a Lancaster bomber from RAF Manston. On May 16th, under the full moon, Operation Chastise was successfully carried out on the Rhine, albeit at great loss of life to both sides. So spectacular was the destruction of the Möhne dam in particular that Roosevelt and Stalin were finally convinced of Britain’s determination to win the European war.

The Boxley Abbey miracle

The Boxley Abbey miracle

Boxley Abbey, north of Maidstone, was home to a celebrated picture of Rumwald, who must hold the record for being the youngest ever saint. He died in Buckingham in 662 at the age of just three days, having already distinguished himself by speaking from birth (in Latin), pronouncing himself a Christian, and even delivering a sermon before expiring. Just to prove his sanctity, Boxley Abbey displayed a holy portrait that was so light that even a child could lift it, but at times became too heavy to move. This faith-enhancing miracle had to be well worth a pilgrimage to witness. After the Dissolution of the Monasteries, however, the secret was revealed: the portrait was held in place with a bolt wielded by a monk hiding behind the partition. It just goes to show how even supposedly pious humans will employ any deceit to make converts, but do not look good when they are found out.

Bradley the Seal

Bradley the Seal

The Pegwell Bay area is well known for its seal population; Maidstone not so much. There was consternation when one turned up in the county town in 2021 and seemed not to know where to go next, what with Allington Lock apparently blocking the way downstream. Hundreds of well-wishers (and one or two mischief-makers) turned up to take a look, and several to lend a hand; but Bradley, as the seal was soon named, was not eager to be helped. Most onlookers assumed that, like a beached whale, this common seal had ventured beyond its safe limits, and no good would come of it. Yet Bradley, who turned out to be a female, knew what she wanted. When she was ready, she left for the sea. Not only that: having decided that she liked the place and the locals, she has been coming back annually, as if for her summer holidays.

Brickearth

Brickearth

Ask most Kent people what brickearth is and they won’t have a clue. It’s a pity, because brickearth is a major reason why Kent became the Garden of England, as well as home to several brickworks. It is in fact so-called ‘loess’ sediment, which in Kent can run to three or four yards deep. To understand where it came from, you have to delve only into the relatively recent geological past. When glaciers thawed out elsewhere, they left behind rich deposits. Because these were powdery, they were whipped up by prevailing winds and dumped in receptive places like river valleys. The Medway and the Stour were particularly endowed. Apart from having an ideal structure for making house bricks, brickearth on top of clay or chalk both drains well and makes it easy for plants to absorb nutrients. If anyone asks why the National Fruit Collection and National Hop Collection are minutes apart, there is the answer.

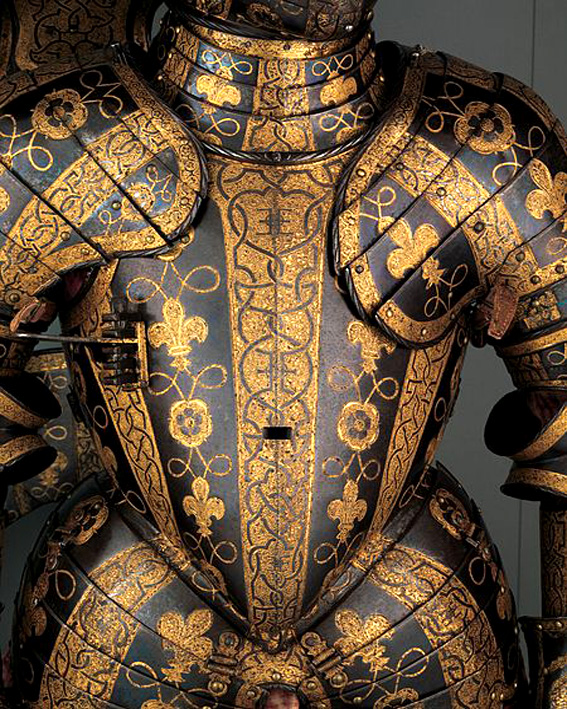

The Buffs

The Buffs

The 3rd Regiment of Foot was the third to be formally established in the English Army. It was however the very first to be raised, having started life in Holland in 1572 as a unit designed to assist the Dutch against Spain. It took its nickname from the dull yellow facings on the men’s red tunics. It saw action at several famous battles, including Blenheim, Culloden, and Sevastopol. When stationed in Malta in 1858, Lieutenant John Cotter coined the phrase “Steady, the Buffs!” which Rudyard Kipling made part of the language. In 1881, the Regiment became the Buffs (East Kent Regiment), based at the Howe Barracks in Canterbury, a ‘Royal’ tag being added in 1935. It merged with the West Kent Regiment in 1961 to form the Queens Own Buffs, but was eventually subsumed into the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment, named in honour of Prince Charles’s first wife. Only the 3rd Battalion (of four) is still based in Kent.

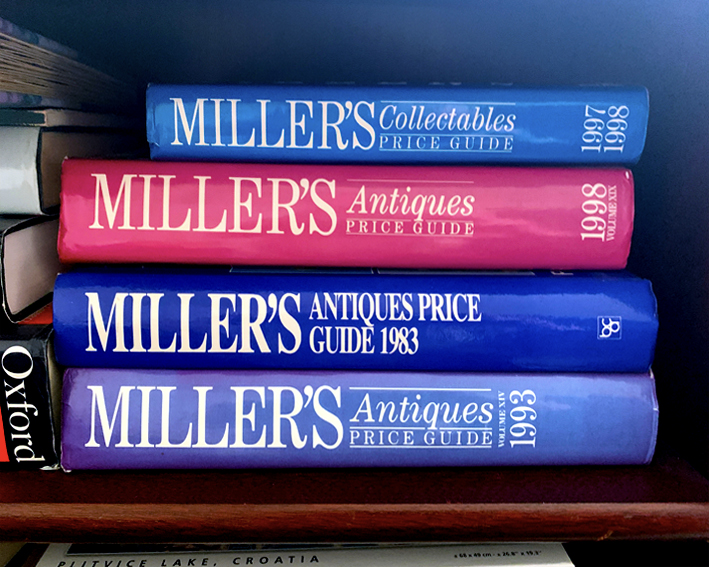

Bunyard’s Fruit-room

Bunyard’s Fruit-room

In his capacity as an expert pomologist, George Bunyard from Maidstone was interested not only in cultivating more productive and tastier strains of apple, but also in ensuring the quality of the harvested product. It was customary in his time to use oasts to store fruit for the winter after they had finished doing their job as hop kilns. The trouble was that any apple piled loosely is liable to bruise and become the rotten one that spoils the barrel. Bunyard’s elegant solution was his ‘Fruit-room’. This was a large rectangular shed constructed out of matchboard over a concrete floor, its top and sides covered with Medway reeds. Inside, tens of thousands of apples were laid out individually on shelves and maintained at a steady temperature in the high 40s Fahrenheit. Apart from being cheap to make (~£30), it was surprisingly durable (>20 years). The idea can still be found in use today, fundamentally unchanged.

Byng’s ‘Tour into Kent’

Byng’s ‘Tour into Kent’

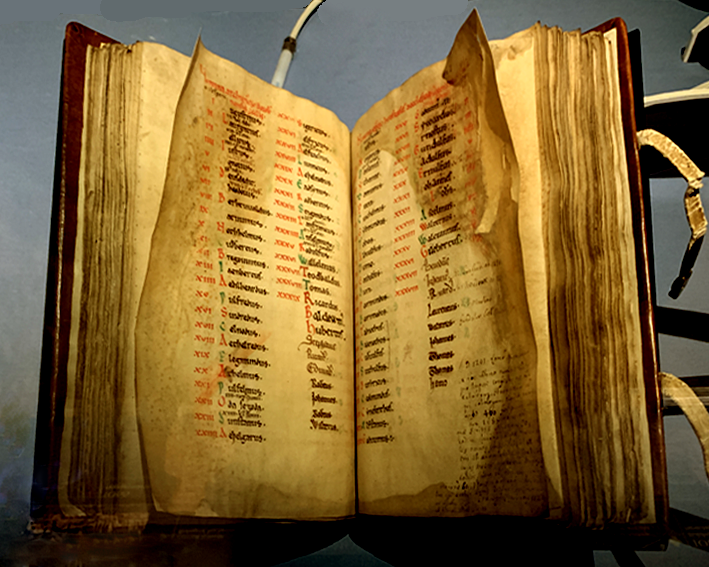

The 5th Viscount Torrington, John Byng from Bedfordshire, was the grandson of Admiral of the Fleet Sir George Byng. Between 1781 and 1794, now a retired army officer, he made and diarised fifteen tours of English regions. In September 1790, it was the turn of Kent: a journey of special significance, as it took him to his grandfather’s ancestral home at Wrotham. His ten-day trip on horseback more or less followed the route of the modern-day A20 to Dover, returning to London on the A2 via Canterbury. Writing in a lively, down-to-earth style, he describes the improvement in roads since his childhood, but misses the old shaded lanes. He also bemoans the poor quality of food, drink, accommodation, and stabling he encounters, and has harsh words for the disrepair of Leeds Castle and Eastwell Manor. Nonetheless, he is proud of England’s heritage, chastising travellers abroad “who drive by Canterbury Cathedral, without deigning a look, and return boasting of rialtos”.

The Callender’s Cableworks Band

The Callender’s Cableworks Band

William Callender set up a business at Belvedere in 1870 refining bitumen. The company diversified into cable production so successfully that, in the 1930s, it played a key role in connecting Belvedere Power Station with the National Grid across the Thames. In the 1890s, a Salvation Army brass band nearby, seeking a broader repertoire, converted to a temperance band. This left it short of uniforms, so Callender’s stepped up as a sponsor in 1898. So many Callender’s employees joined that they eventually boasted four bands of varying ability. The senior band itself became sufficiently proficient to be considered the best brass band outside of the Northern colliery towns that were brass bands’ heartland. It featured regularly on BBC Radio before WW2, and won 25 competitions; it also opened the new art-deco frontage of Herne Bay bandstand in 1932. With a new musical tidal wave approaching, the band disbanded in 1961.

TSS Canterbury

TSS Canterbury

Southern Railway’s ferry ‘Canterbury’ was the Black Beauty of shipping. She was a twin-screw steamer built at Dumbarton in 1928 to provide the Dover to Calais connection between the new Golden Arrow and Flèche d’Or rail services linking London and Paris. Originally intended to be 1st-class only, she was converted also to take 3rd-class after just two years. In 1940, commandeered by the Royal Navy as HMS Canterbury, she took part in the Dunkirk evacuation, narrowly surviving a bomb blast but completing five runs. Sent to the River Dart, she was used by the Fleet Air Arm for target practice, but was then converted for use in the Normandy landings. Having survived all that, she returned to her old duties at Dover, but was replaced by the new ‘Invicta’ in 1946. She finished her life operating a service between Calais and Boulogne, made a cameo appearance in ‘The Lavender Hill Mob’ (1951), and was broken up in 1965.

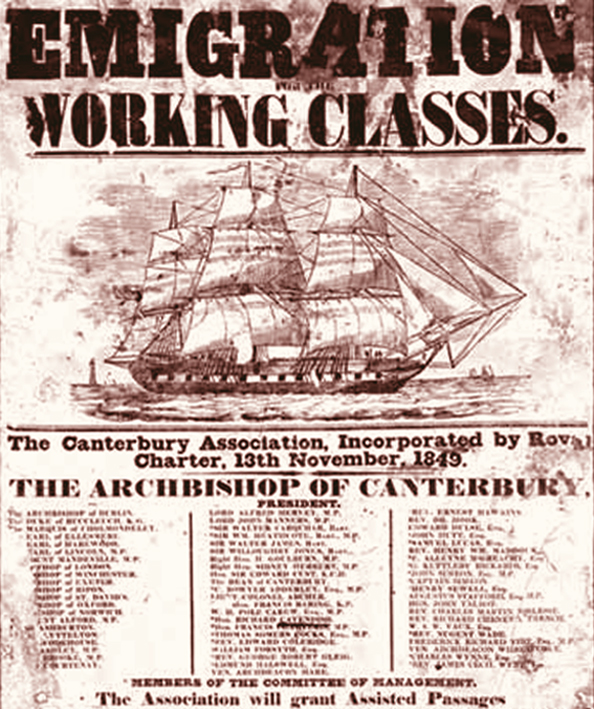

The Canterbury Association

The Canterbury Association

In 1848, a Londoner and a Dubliner, Edward Wakefield and John Godley, had the idea of building a self-sustaining community sponsored by the Church of England on New Zealand’s South Island. The body they founded to plan it, containing numerous clergymen and politicians, was incorporated by Royal Charter in 1849. Its management committee was presided over by the Archbishop of Canterbury, for which reason it was called the Canterbury Association. Having decided that the new colony should also be called Canterbury, they recruited settlers from diverse backgrounds to ensure complementary skills, and set about building houses and roads in advance. To get settlers to the destination, they acquired the so-called First Four Ships, three of which set off in September 1850 from Gravesend and rendezvoused with the fourth at Plymouth before setting sail. These ‘Canterbury Pilgrims’ ended their three-month voyage near modern-day Christchurch, which itself was named after Canterbury Cathedral.

Canterbury College, Oxford

Canterbury College, Oxford

‘University Challenge’ fans are familiar with Balliol, Keble, and St John’s; but Canterbury College, Oxford? There once was such a thing, and it was a Kentish creation. In 1311, four monks from Christ Church priory in Canterbury were sent to study at Oxford in a hall close to the eastern city wall. A half century later, the project was expanded to a full college, situated just south-west of Oriel College. It came to an abrupt halt in 1540, when Henry VIII’s lucrative Dissolution of the Monasteries was expanded to include anything with monks in it. The college was closed down and the property redistributed to the erstwhile Cardinal College, named after Wolsey, which was briefly renamed Henry VIII’s College following the Lord Chancellor’s demise. Presumably in deference to Canterbury, the King renamed both the college and its chapel, Oxford Cathedral, as Christ Church. Its hall is now familiar to Harry Potter fans as Hogwarts’ Great Hall.

The Canterbury Cross

The Canterbury Cross

The original Canterbury Cross was unearthed in 1867 during excavations in St George’s Street, Canterbury. It turned out to be a Germanic brooch dating to around 850. So artfully conceived was it that it gave rise to a standard design also known as the Canterbury Cross. What makes it special is the ingenious way in which the Christian cross’s angular look is softened to a more rounded affair that gives an impression of eternity, whilst it also incorporates ‘triquetra’ shapes suggesting the Holy Trinity. So elegantly does the design combine these concepts that it might in the modern age have won an award as a corporate logo, as evidenced by the Church of England‘s decision in 1937 to send a stone replica to each of 91 Anglican cathedrals around the world; another is mounted in Canterbury Cathedral. The bronze original, inlaid with silver and niello, is meanwhile displayed in Canterbury’s Beaney House of Art & Knowledge.

Canterbury Pace

Canterbury Pace

Anyone wanting to make a medieval pilgrimage from Winchester to Canterbury faced the prospect of a sore bottom. Proceeding on horseback at a walk might demand a travel time of 30 hours. Even at a trot, the trip necessitated something like 15 hours’ riding, with the same to follow on the way back; so it mattered to achieve a good but sustainable pace. It seems that pilgrims did find an optimal speed that their horses could tolerate, which came to be known as ‘Canterbury Pace’. According to etymologists, this may have been abbreviated to the modern equestrian term, a ‘canter’. It seems unlikely, however, that it would have matched a modern canter, which typically exceeds 12 mph – a challenging tempo for the small horses of the day on rugged by-ways. What can be said for sure is that Trottiscliffe did not lend its name to the trot, even if it is on the Pilgrims’ Way.

The Canterbury Scene

The Canterbury Scene

What’s strange about the Canterbury Scene is that there never was much of a Canterbury scene. The term refers to a group of North Kent musicians who shared an interest in psychedelic jazz seguing into progressive rock. Two men at the heart of it were singer-guitarist Kevin Ayers from Herne Bay and singer-drummer Robert Wyatt, who lived at Lydden. After leaving Simon Langton Grammar School in Canterbury, the two formed the Wilde Flowers, playing psychedelic rock, in 1964. The two left after five years to form Soft Machine, which early on rivalled Pink Floyd; the two bands twice appeared together at Canterbury Technical College, though their fortunes diverged dramatically thereafter. Ayers went on to work with several top names in the music industry, while Wyatt was paralysed after falling out of a window at a party. Meanwhile, their former Wilde Flowers bandmates back in Whitstable became Caravan, a prog rock band still active today.

A Canterbury Tale

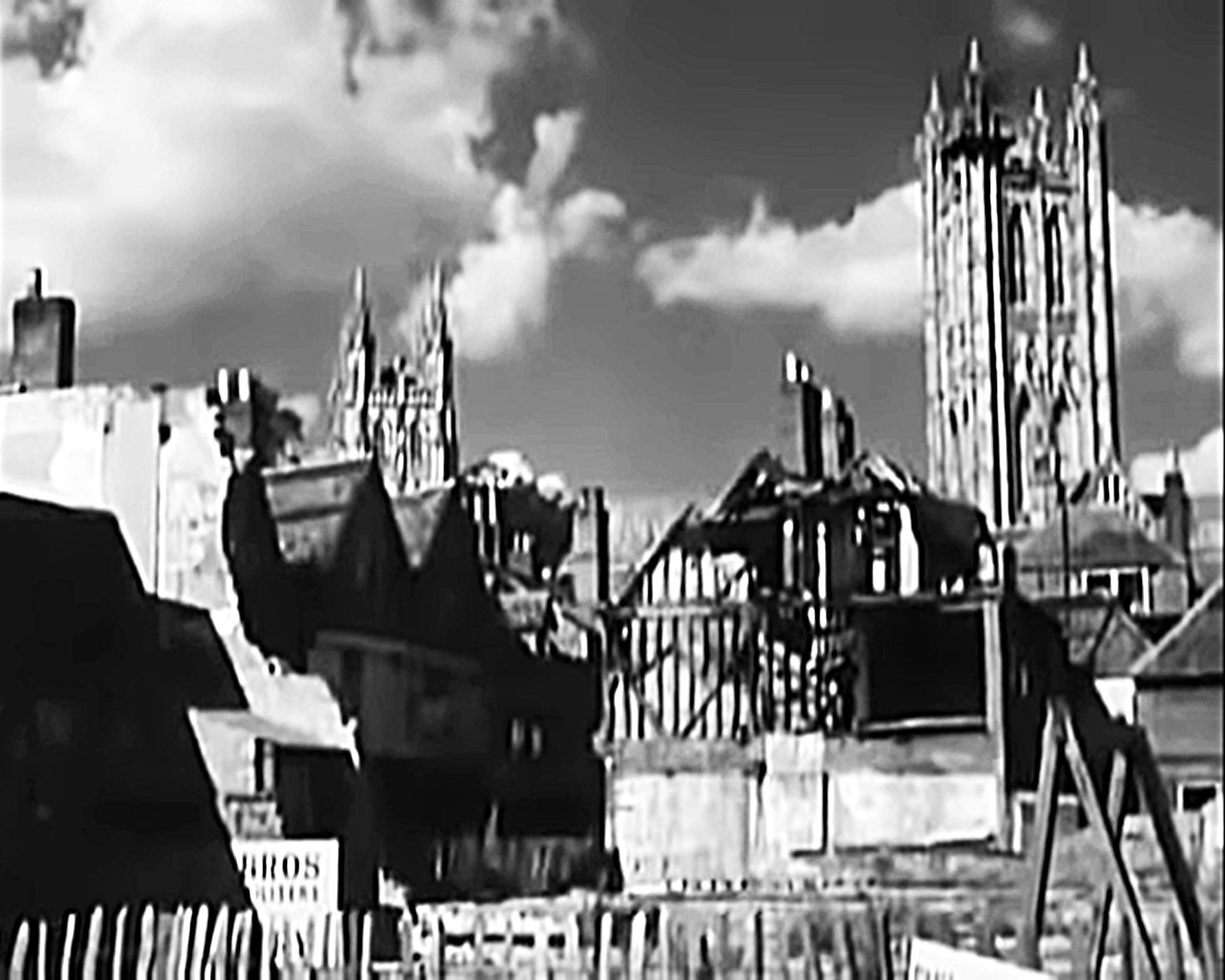

A Canterbury Tale

Canterbury-born film director Michael Powell made ‘A Canterbury Tale’ in 1944 under the aegis of The Archers, his outstanding collaboration with Emeric Pressburger. Starring Eric Portman, Dennis Price, and Sheila Sim, it was a gentle wartime propaganda piece intended both to consolidate Anglo-American camaraderie and to remind the English what they were fighting for. The movie depicts a latter-day pilgrimage of sorts: a journey to Canterbury that provided Powell with an opportunity to show off Kentish rural life at its best. It starts in the imaginary village of Chillingbourne, featuring scenes shot in Chilham, Fordwich, Wickhambreaux, and elsewhere. After a rail journey to Canterbury, it culminates in a spine-tingling performance of Bach’s ‘Toccata and Fugue in D Minor’ by Price’s character on the Cathedral organ, followed by Sim’s heart-wrenching perambulation through the city centre recently devastated by the Luftwaffe. Though not much of a story, it is a remarkable document of Kent’s wartime experience, before the doodlebugs arrived.

The Canterbury Tales

The Canterbury Tales

Geoffrey Chaucer’s ‘The Canterbury Tales’ (1400) was the first text in English to become world-famous. It is a collection of 24 stories supposedly told on a pilgrimage from Southwark to Canterbury. The thirty or so pilgrims depart from the Tabard Inn, each charged with telling tales en route; the teller of the best will win a free dinner. The idea was not original – Boccaccio’s ‘Decameron’ preceded it – but Chaucer’s tales are consistently entertaining and varied. ‘The Canterbury Tales’ was written in Middle English, a double-edged sword insofar as the language is delightfully earthy, but a deterrent to the casual reader. For that reason, TV dramatisations have proved popular, bringing a colourful mix of satire and bawdiness. Each pilgrim was supposed to tell four tales, but Chaucer ran out of life before finishing, even after spending 13 years on them. Nevertheless, it’s debatable whether more Americans and Australians have heard of Canterbury through the Cathedral, or the Tales.

Canterbury Tart

Canterbury Tart

The English are not renowned for making world-class desserts. One of our best, however, is apple tart; and it is no wonder that one of our best apple tarts bears a name associated with the nation’s leading apple-growing county. The Canterbury Tart has a dessert-apple and lemon base covered by overlapping sliced apples, baked for 45 minutes and delicious served with a little cream or ice-cream. Numerous variants have been published, all of them simple to prepare and certain to bring satisfaction to several. The dish gets its name, extraordinarily, from none other than Geoffrey Chaucer of ‘Canterbury Tales’ fame. He provided the first written recipe for apple tart, specifying good apples, good spices, figs, raisins and pears, all cut up and coloured with saffron. That recipe is traditionally dated to 1381. Although the date is not easily corroborated, it may be worth bearing in mind that its 650th anniversary comes up in about a decade.

The Canterbury Theatre of Varieties

The Canterbury Theatre of Varieties

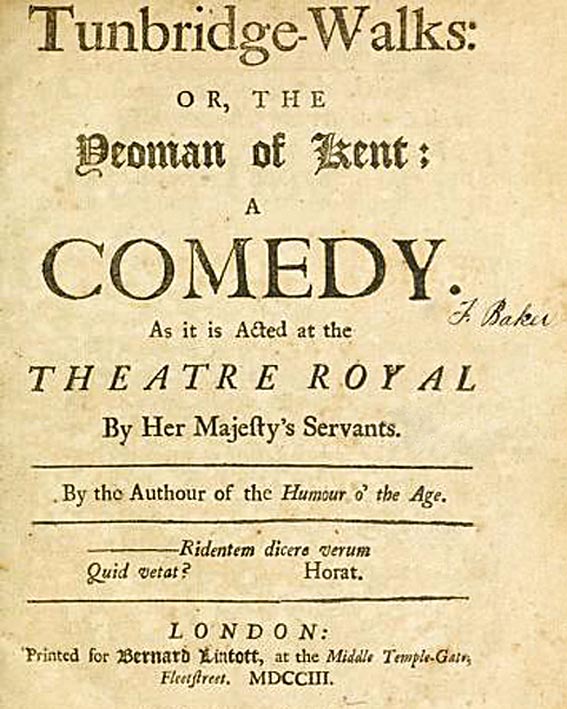

By a string of chances, one of London’s most fashionable pleasure palaces got its name from Kent’s holiest spot. Around 1200, the Archbishop of Canterbury acquired Lambeth Manor on the south bank of the Thames as his residence in the capital, and Lambeth Palace evolved on the site over the centuries. In the C18, a pub just the other side of what is now Archbishop’s Park was renamed the Canterbury Arms Tavern in His Grace’s honour. Like other such hostelries, it offered entertainment, specifically by way of a skittles alley next door. Pioneering impresario Charles Morton replaced it in 1852 with the Canterbury Hall, a music hall that proved an immediate success. By the end of the century it had been expanded, embellished, and renamed repeatedly, and a night at the ‘Canterbury’ was a much imitated institution, with such celebrities as Little Tich and Charlie Chaplin performing there. The Luftwaffe demolished it with a direct hit in 1942.

The Canterbury Treasure

The Canterbury Treasure

Having been populated since time immemorial, Kent naturally has its fair share of hoards. These range from such Late Bronze Age finds as a collection of 17 gold bracelets unearthed in 1906 at Bexley to a collection of 352 bronze objects found in 2011 at Boughton Malherbe including tools, weapons, ornaments, and even moulds from which they were made, suggesting a workshop. The biggest Roman hoard was 3,600 C4 bronze coins at Snodland (2006); but the most poignant has to be the collection of engraved silver spoons and other high-status artefacts unearthed by workmen close to Westgate in Canterbury in 1962. A coin found with them dates them to after 402 AD, 410 being the year in which Rome effectively abandoned Britannia. One can well imagine the owner burying them in the belief that he or she would soon be back; but the withdrawal was to prove permanent. The collection is displayed at the Roman Museum in Butchery Lane.

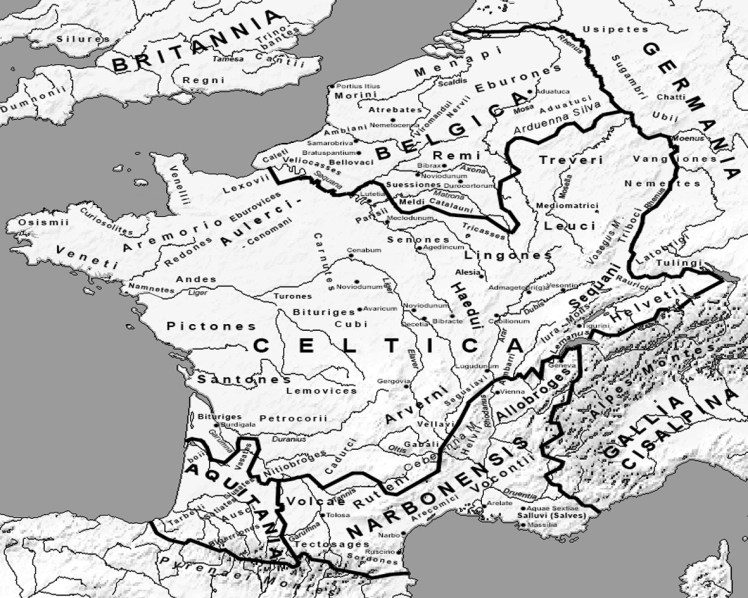

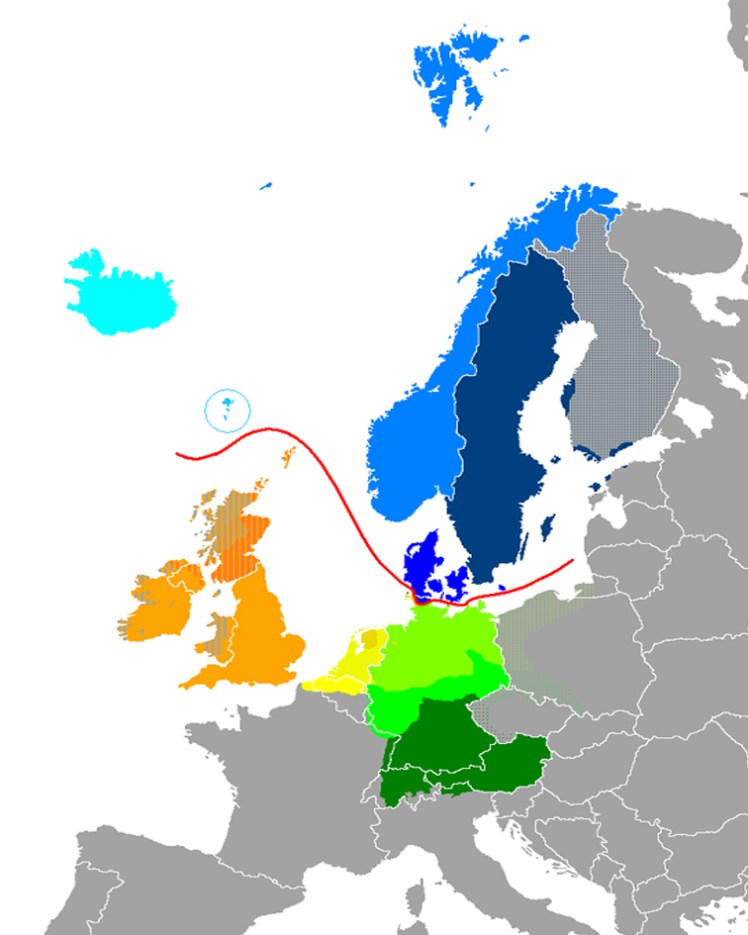

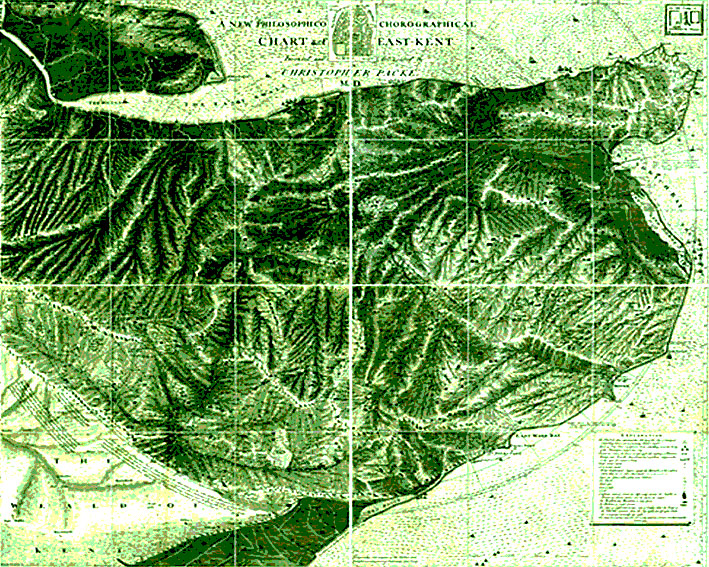

The Cantii

The Cantii

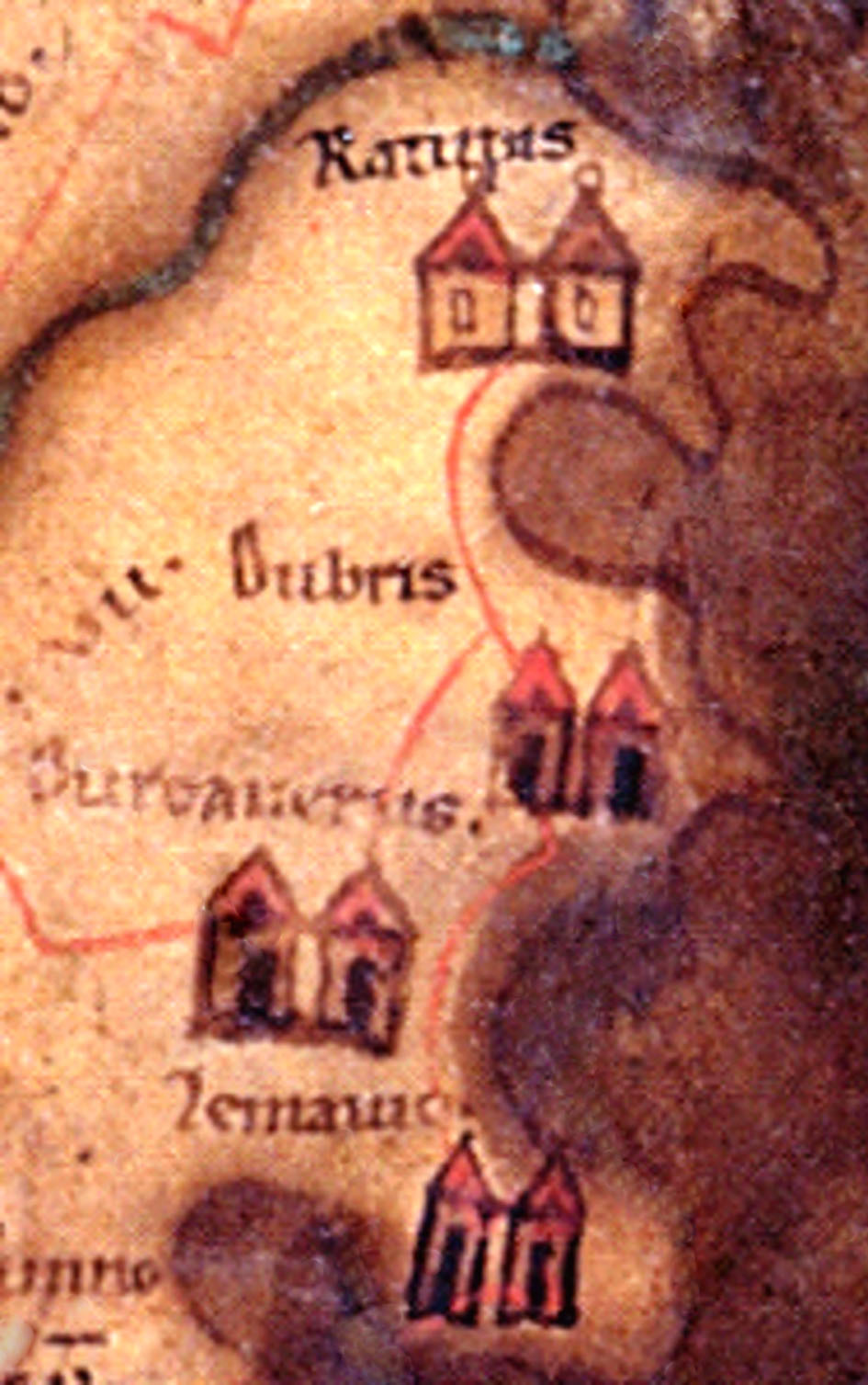

Kent got its name from the Cantii, or Cantiaci, a Bronze Age tribe that emigrated across the Channel from Northern Europe, or possibly the Baltic, probably in the C2 BC. Their favourable location, close to mainland Europe, gave them such a cultural and economic lead that Julius Caesar described them as the most civilised people in Britannia. They did not have a single polity: Caesar recorded four contemporaneous kinglings, namely Segovax, Carvilius, Cingetorix, and Taximagulus. Their territory was even larger than the historical Kent that endured until 1889, additionally embracing parts of Sussex (including Hastings), Surrey, Middlesex, and Essex. Among Cantium’s Roman-era settlements, the C2 Greco-Roman geographer Claudius Ptolemy listed their capital Durovernum Cantiacorum (Canterbury), Durobrivae (Rochester), Rutupiae (Richborough), and a port on the north bank of the Thames called Londinium. In 1886, archaeologist Sir John Evans, father of the famous Sir Arthur, excavated the Cantiian ‘Aylesford Bucket’ (C1 BC) now held at the British Museum.

‘Carrington VC’

‘Carrington VC’

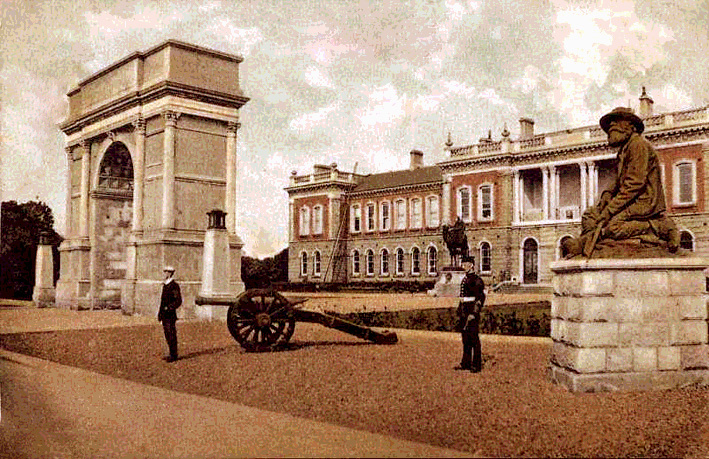

This 1954 black & white movie is the kind at which Anthony Asquith, the son of a former prime minister, used to excel: a taut drama, economically told and expertly acted. Starring David Niven as a Royal Artillery major, it revolves around a military trial (whence its American title, ’Court Martial’) engineered by a superior officer who is jealous of the eponymous character’s wartime heroics. Although the interior action was shot at Shepperton, what lent the action particular authenticity was the outdoor scenes, filmed over a period of two weeks at the Woolwich Barracks thermselves. Featuring footage of actual RA soldiers on parade, the movie represents a vivid antiquarian record of this once hugely important British Army unit shortly after WW2, when it was commencing its long, slow depletion. Just two years later, it was decided that, though the regimental headquarters would remain there, much of the historic barracks would be demolished and replaced.

Chain Home (CH)

Chain Home (CH)

The CH early-warning system was a product of an age when Britain still valued genial geniuses over noisy know-alls. It was prompted by an assertion of Prime Minster Stanley Baldwin in 1932 that “the bomber will always get through”. One English boffin, Arnold ‘Skip’ Wilkins, sat down to ponder whether that had to remain the case. He worked out how to detect incoming bombers by the canny use of radio waves. By 1937, with the Nazi menace growing, five experimental stations were built under the codename ‘Chain Home’. There were two in Essex and one in Suffolk, but the forward-most were on opposite sides of Kent, at Dunkirk and Swingate. Recognisable by their multiple radar aerials, they were subjected to repeated bombing once WW2 started, but kept going. By the end of the War, there were more than forty nationwide. It’s been estimated that CH tripled the RAF’s fighter capability, beating off Germany’s far superior force by pitching brains against Braun.

Chapel Down

Chapel Down

The Romans introduced wine-making to Britain, and there were over a hundred vineyards in England in the Tudor period; but the weather militated against both scale and quality. After heavy duties were imposed on French wine in 1703, the British developed a preference for fortified wines like port and sherry. It is global warming that has created a sea-change in recent decades, with a proliferation of brands emerging. Kent’s southerly latitude and limestone soil give it an advantage that has been richly harvested by Chapel Down. The business is named after a vineyard on the Isle of Wight that in 1995 acquired Rock Lodge of Tenterden, where its new headquarters was set up. Five years later, Chapel Down merged with Lamberhurst. The company is now the biggest wine-producer in the UK, and has established a national reputation for quality produce that includes, unprecedentedly, English sparkling wines that do not disappoint. The visitor centre plays host to 50,000 annually.

Chaplin’s

Chaplin’s

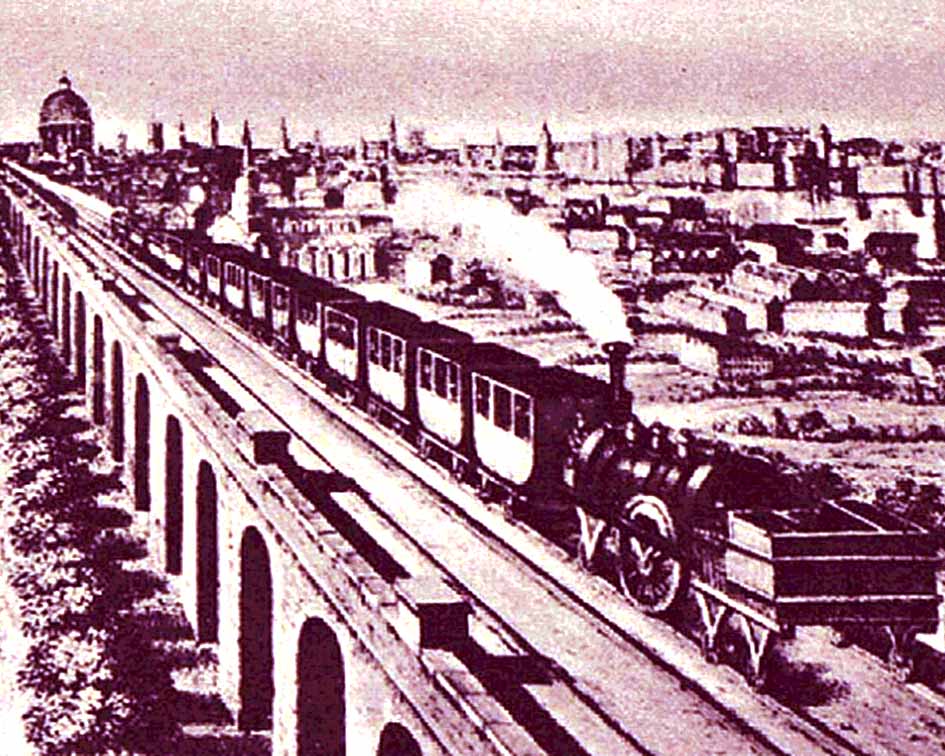

In the Georgian era, the name Chaplin was not universally associated with a bowler hat and funny walk, but horse-drawn coaches. William Chaplain or Chaplin (1787–1859) was a coachman of humble origins in Rochester who exhibited an outstanding entrepreneurial streak. He built a network of coaching services that eventually extended around the country, and by 1835, with up to 1,500 horses, 68 carriages, and several depots at its disposal, was a household name. Much the biggest business in the field, it was reckoned to be making around half a million pounds a year. But Chaplin was not complacent. When the railways started to impinge, he responded proactively, becoming deputy chairman of the London & Southampton Railway, later famous as the London & South Western Railway. He went into partnership to form a road-and-rail haulage business, Chaplin & Horne, that was eventually taken over by Pickfords. In later life, Chaplin became Sheriff of London and an MP.

Charlton Horn Fair

Charlton Horn Fair

The Charleton Horn Fair was one of the most riotous occasions of this or any county. One legend has it that King John, caught in flagrante with a miller’s wife, assuaged him with cash that paid for a fair every St Luke’s Day, and a patch of land that became known as Cuckold’s Point – the traditional symbol of the cuckold being horns. More prosaically, it may just be that Charlton Church was St Luke’s, and the saint was always depicted alongside a horned ox. Whatever the case, the custom arose of wearing horns at the annual fair. But behaviour grew more outrageous than wearing fancy dress. It became such a pretext for lascivious and drunken behaviour that Daniel Defoe complained bitterly about the “yearly collected rabble of mad-people”. Unsurprisingly, it was too much for Victorian propriety, and was banned in 1874. The Horn Fair was revived in 2009, although no doubt with a more sophisticated ethos.

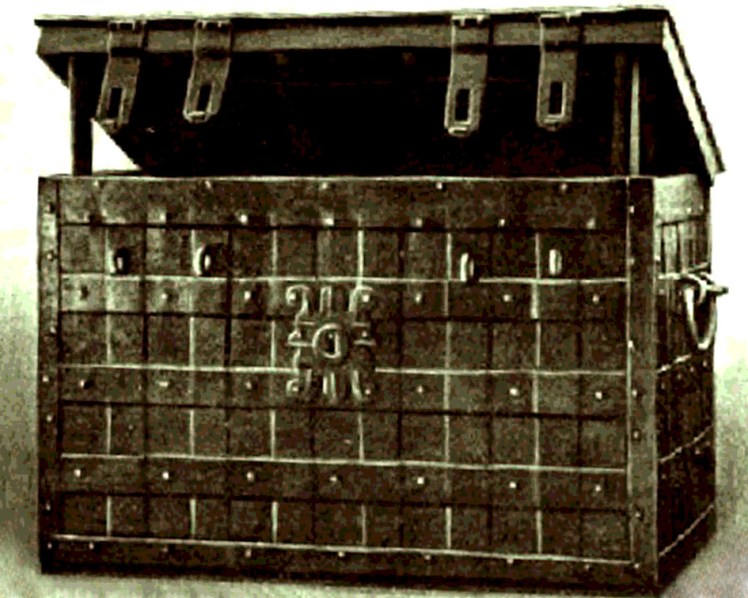

The Chatham Chest

The Chatham Chest

The war between England and Spain in the late C16, culminating in the defeat of both Spanish and English armadas, brought a toll in disabled sailors. Agitation for financial help induced the Lord High Admiral to press their case with Elizabeth I. The outcome was a pension fund that came to be known as the Chatham Chest. For 155 years from 1594, one thirtieth of every seaman’s pay – typically sixpence a month – was deducted for the fund. Payments were made to sailors according to the extent of their loss: an armless man, for example, earned £15 a year. The funds were kept in a literal chest, a strong box guarded by the Royal Marines at Chatham Dockyard. It had five locks, whose keys were held by five separate functionaries. It didn’t stop large-scale theft by officials; and Charles I exercised his Divine Right to steal the whole lot. It was eventually merged into the Greenwich Hospital fund.

Chattenden Camp

Chattenden Camp

Following the Dutch Raid on the Medway, the armed forces began to store gunpowder at Upnor Castle. As demand grew during the C19, large new magazines were created piecemeal nearby. In 1875, however, a tidier solution was sought, and five magazines were built behind a natural blast wall at Chattenden, nearly three miles north of Chatham over on the Hoo Peninsula. Designed to store at least 40,000 gunpowder barrels, they were defended by the Chattenden barracks built three years earlier, and served by the Chattenden & Upnor Railway. Originally shared between the Army and Navy, they were placed in sole possession of the former from 1891, but assumed by the latter in 1903. Although the magazines ceased to be used in 1961, they still stand, having subsequently been used for general storage. The barracks and training areas survived into the C21, and eerie relics can still be seen behind barbed wire along Lodge Hill Lane.

‘Churchill’s Grave’

‘Churchill’s Grave’

In Charlton cemetery at Dover lies the grave of Charles Churchill (1732-64), a London-born, Cambridge-educated poet whose funeral there was embellished by a monument in St Mary’s church. Churchill was a classic C18 libertine, a member of the notorious Hellfire Club. He wrote satirical pieces lampooning William Hogarth, Dr Johnson, and Lord Sandwich among others, but was most popular for his ‘Rosciad’ (1761), which ridiculed London actors and actresses. He died of a fever at 32 in Boulogne, where he had gone to meet his friend, the outlawed radical John Wilkes; another Hellfire member returned his body for burial in Kent. Half a century later, Lord Byron came to pay his respects, and was struck by Churchill’s anonymity in this graveyard full of forgotten souls. He recorded his dismay in a poem called ‘Churchill’s Grave’, beginning “I stood beside the grave of him who blazed/The comet of a season, and I saw/The humblest of all sepulchres…”.

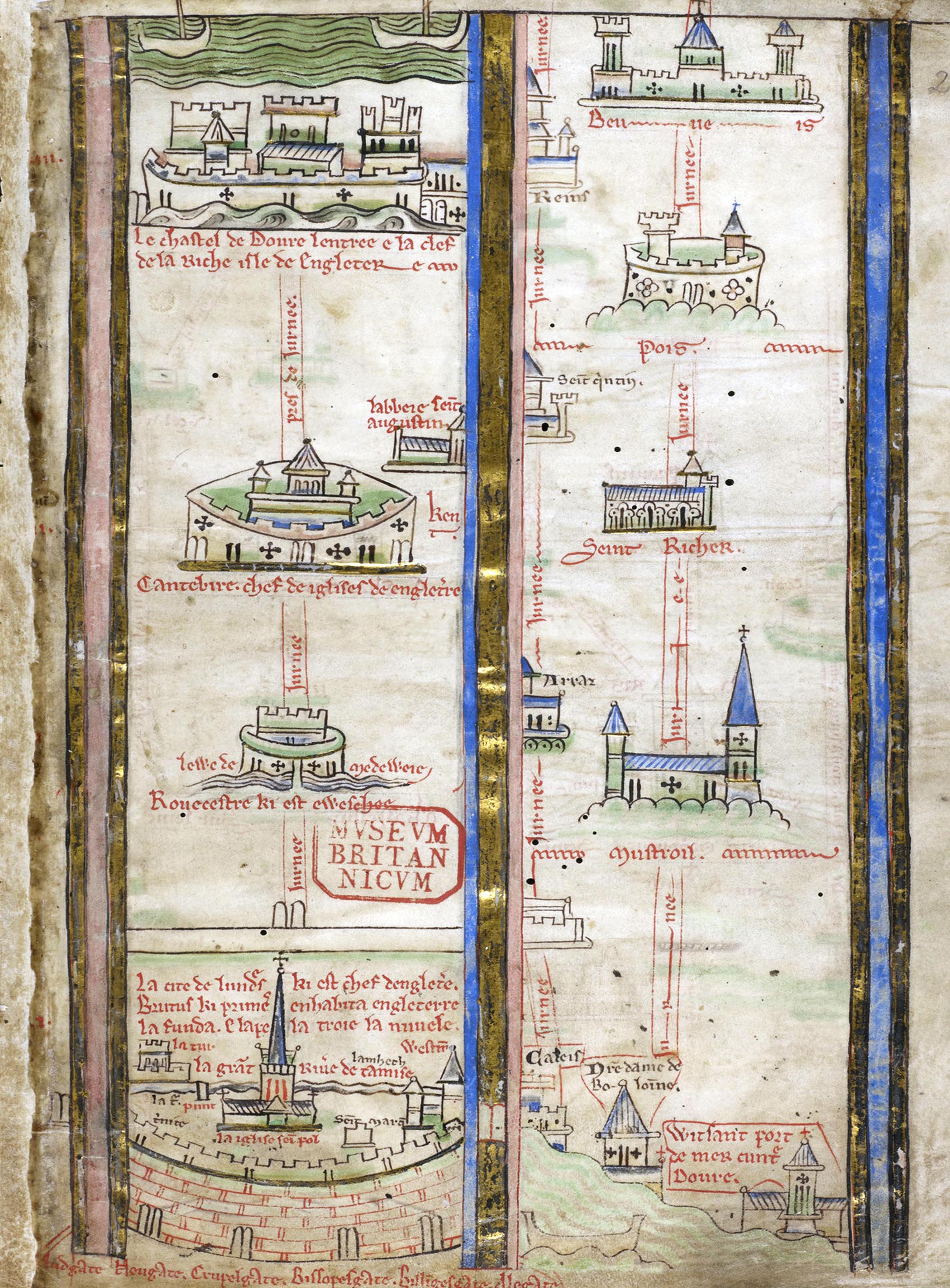

The Cinque Ports

The Cinque Ports

The Confederation of Cinque Ports came about in response to the King of England’s need to have ships at his disposal. Since the kings of the day were Normans, the agreement struck with (mostly) Kentish coastal towns still has a French name. It was formalised by royal charter in 1155. In return for providing 57 ships for 15 days a year, the participating towns could enjoy privileges including certain tax, justice and salvage rights. The initial Kent participants were Sandwich, Dover, Hythe, and New Romney, with Hastings making up the five. They changed from time to time, for example when New Romney harbour silted up and was replaced by Rye. There were also associated ‘limbs’ like Folkestone and Ramsgate, as well as numerous ‘connected’ towns and villages. The practical arrangement died out by the C15, but the honorific post of Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports still entitles the holder to reside at Walmer Castle.

The Cleveleys

The Cleveleys

John Cleveley senior (1712-77) was born in Surrey and, in accordance with his father’s wishes, became a navy carpenter at Deptford dockyard, later serving on HMS Victory. His passion, however, was for art. Guided by his technical knowledge, he produced many accurate depictions of navy ships as well as Kent dockyards. One of his sons, James, was also a carpenter, and travelled with Cook on his 3rd expedition; but his others, Deptford-born twins John junior and Robert, were artists. Like him, they both worked in dockyards, and probably both got tuition from Paul Sandby of the Royal Military Academy. More liberal in style and diverse in subject matter, they exploited public interest in naval matters commercially, with dramatic paintings of dockyards, ships, combat, and South Sea scenes. John junior (1747-86), who accompanied Joseph Banks on one journey, died young, probably at Deptford, while Robert (1747-1809) fell off a cliff at Dover.

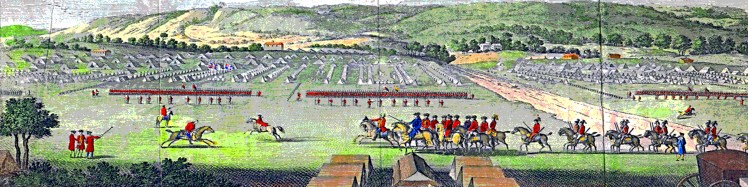

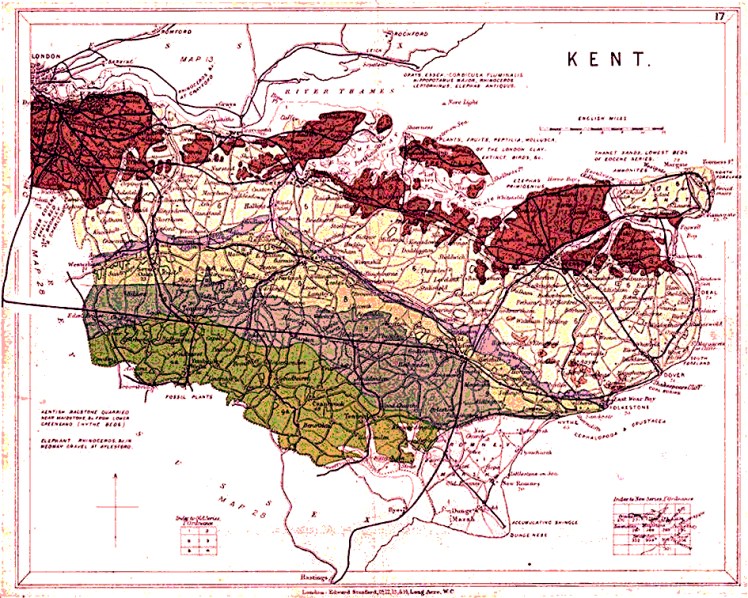

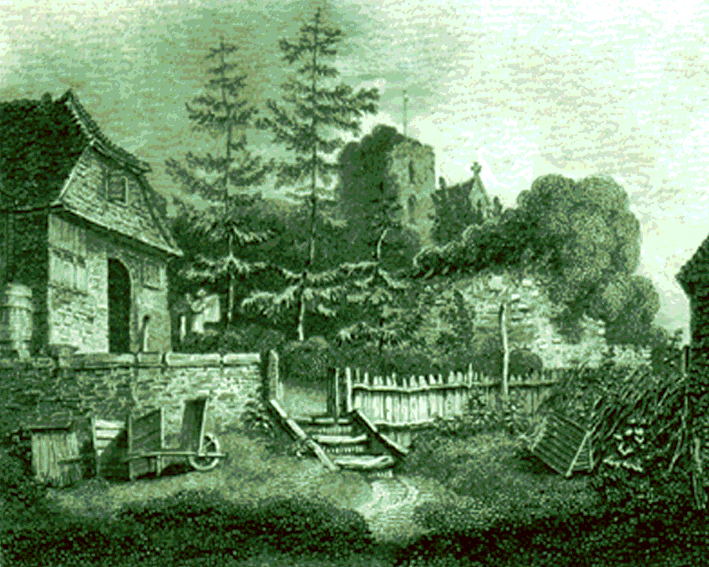

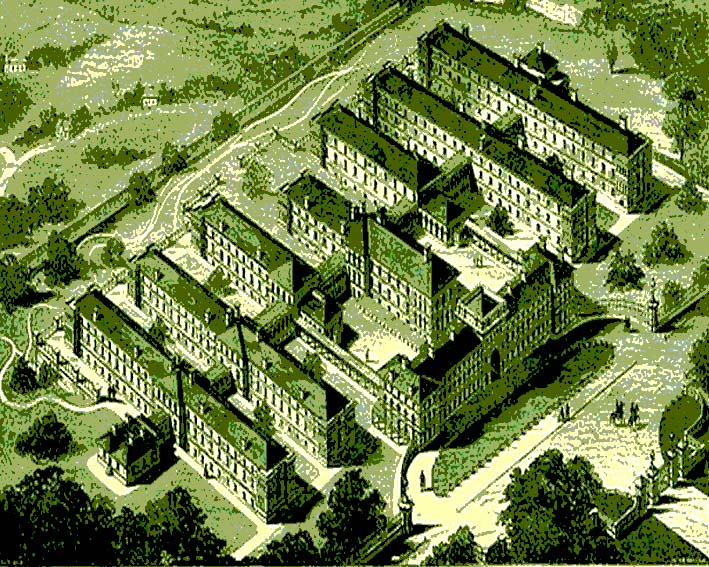

Cocks Heath

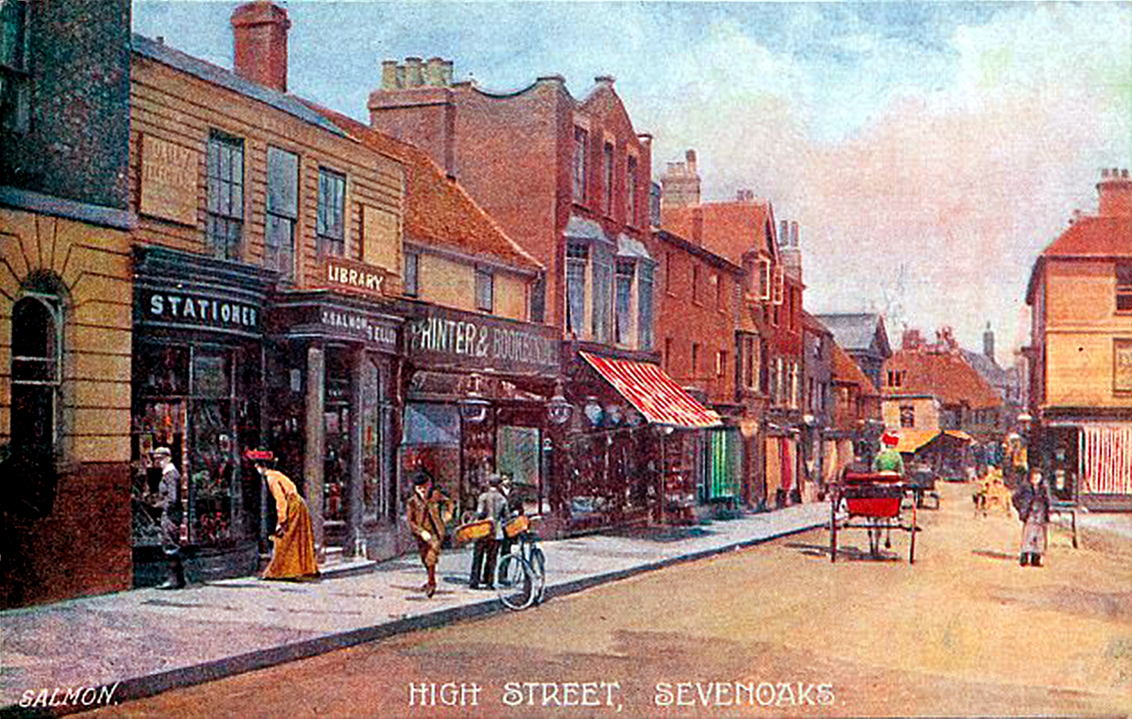

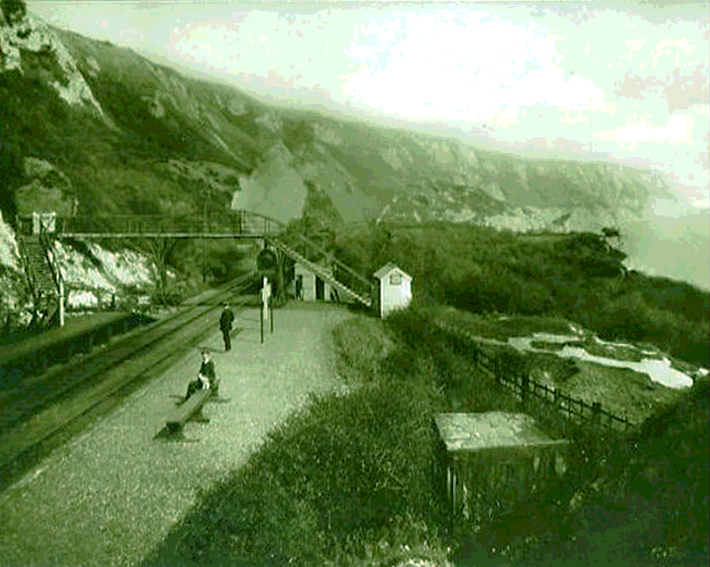

Cocks Heath

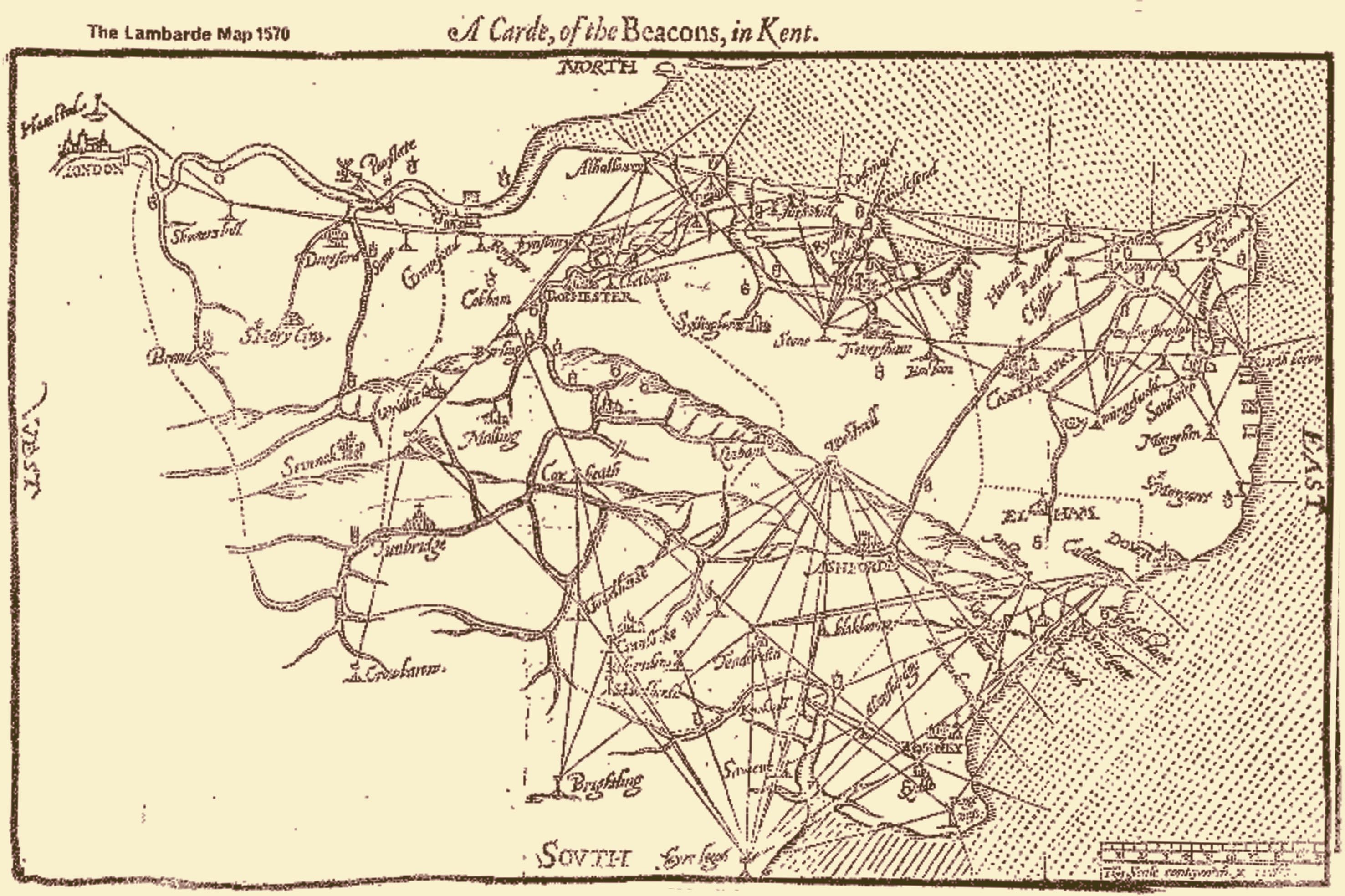

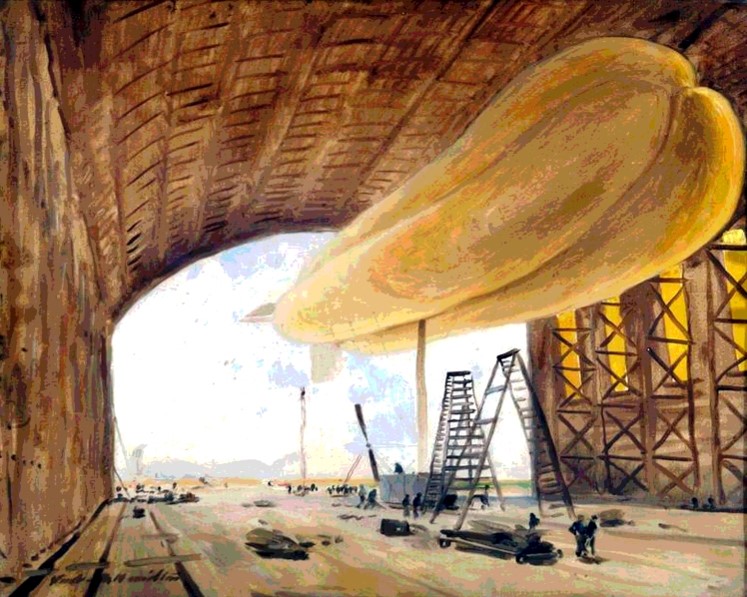

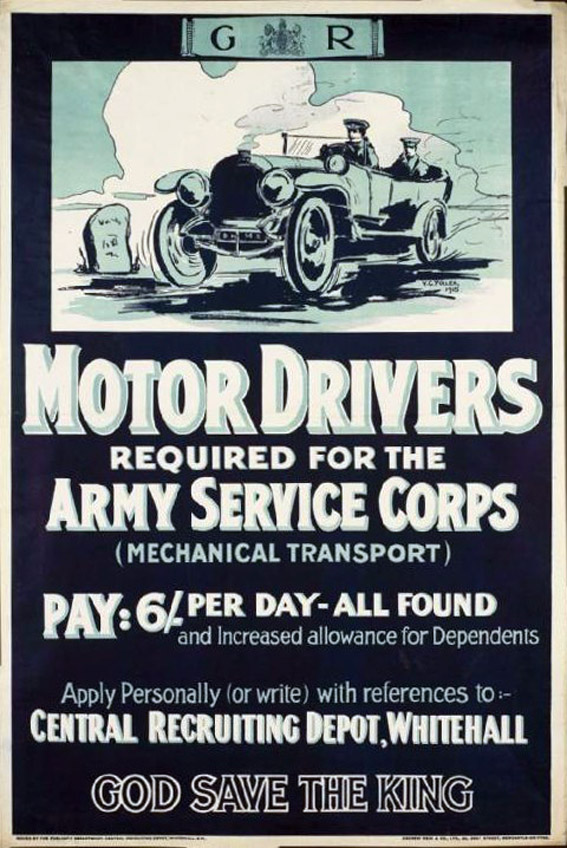

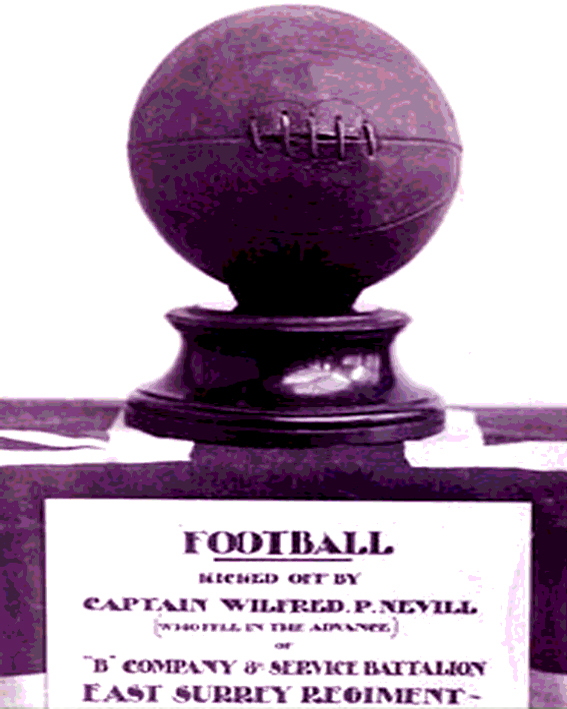

The housing estate that now constitutes Coxheath occupies an area that was once a nationally infamous military camp. Initially occupied in 1756, it was so large – three miles by one – that it was able to accommodate 15,000 troops and their wives during the American Revolution. This made it a significant town in its own right, and traders poured in from London and Maidstone to cater for them. So too did prostitutes, and the nefarious goings on suggested the nickname ‘Cocks Heath’. Light relief from weapons training was provided by the Duke of Devonshire’s celebrity wife, whose cavorting with fashionable friends became a source of national chatter. The great playwright RB Sheridan even co-wrote a popular musical entertainment about it, called ‘The Camp’. It was of course of no avail, because the intervention of the French swung the Revolution decisively in favour of the rebels. After Waterloo, France and England made up for good, and the heath reverted to farmland.

The Coffin Stone

The Coffin Stone

The Coffin Stone – alternatively known as the Table Stone – is something of a misnomer. It refers to a 14-foot by 9-foot block of sandstone lying flat close to the Pilgrims’ Way about a quarter-mile from Kit’s Coty, north of Maidstone. For one thing, any resemblance to either a coffin or table has been somewhat obscured ever since three smaller stones were placed with it. For another, it probably used to stand upright, but fell over. It was long thought to have been part of a long barrow, a communal grave typical of the Neolithic era, and human remains were indeed found underneath when it was lifted in 1836. The absence of matching megaliths nearby gives the lie to this theory, however, although it might have been moved there about five centuries ago from one of the other Medway neolithic sites. Being alongside a public footpath, it can easily be inspected at close quarters.

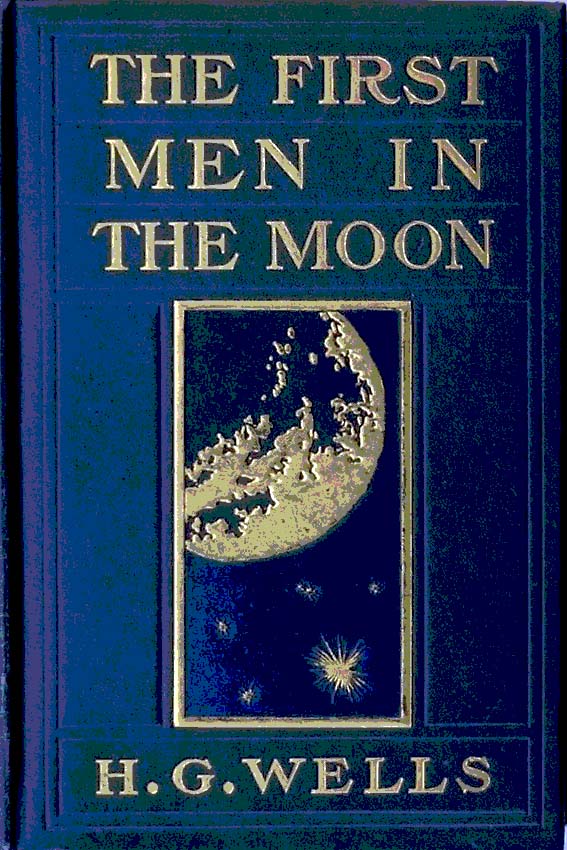

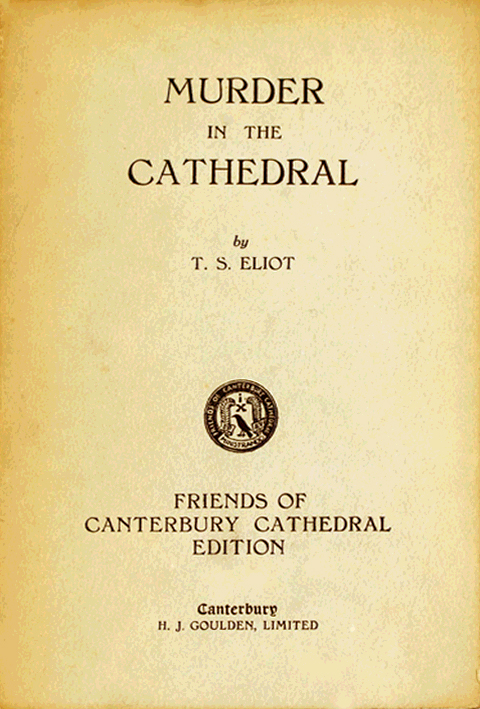

‘The Coming of Christ’

‘The Coming of Christ’

In 1927, the dean of Canterbury Cathedral, George Bell, persuaded John Masefield (1878-1967) of ‘Sea Fever’ fame to write a nativity, ‘The Coming of Christ’, and Gustav Holst to set it to music. Bell secured permission to perform it in the cathedral nave during his 1928 Canterbury Festival, making it probably the first new mystery play since the Middle Ages. Holst took the challenge seriously, importing choristers of his own from St Paul’s Girls’ School to reinforce the local musical talent. Although his pleasingly simple choral music was crowned by a grand finale in which the audience joined in whilst the bells tolled above, the piece was not entirely successful. The music was punctuated by verbose prose passages that stifled its momentum, and concluded with a frustratingly short trumpet voluntary. Although Masefield became a long-standing poet laureate two years later, the work disappeared in England for eight decades. It was finally revived in 2010, with Masefield’s contribution considerably redacted.

Coronation Chicken

Coronation Chicken

After attending Le Cordon Bleu cookery school at Paris, Rosemary Hume (1907-84) from Sevenoaks opened a cookery school in London in 1931 with fellow alumna Dione Lucas, followed by L’École du Petit Cordon Bleu in Sloane Street. So striking was her culinary expertise that the much older flower-arranger Constance Spry offered to write a book showcasing her best dishes. Having no literary skills, Hume agreed, and the ‘Constance Spry Cookery Book’, credited to Constance Spry & Rosemary Hume, became a familiar feature on the kitchen bookshelf. In 1953, possibly suggested by the Jubilee Chicken created for George V in 1935, Hume designed a dish specially for Queen Elizabeth‘s coronation that she initially called Poulet Reine Elizabeth. Unusually for the period, it was made with curry powder, possibly because her father, a British Army colonel, had been stationed in India. A simple way to use up leftover chicken deliciously, the dish caught on under its now traditional name, Coronation Chicken.

The Crab & Winkle line

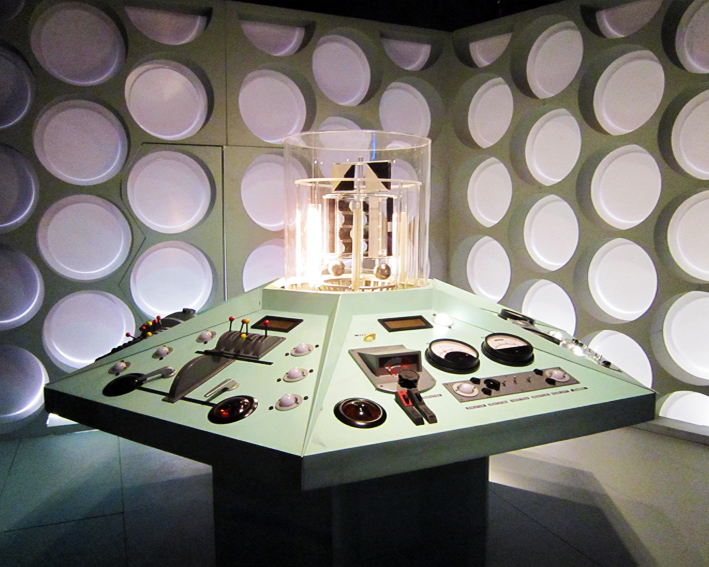

The Crab & Winkle line

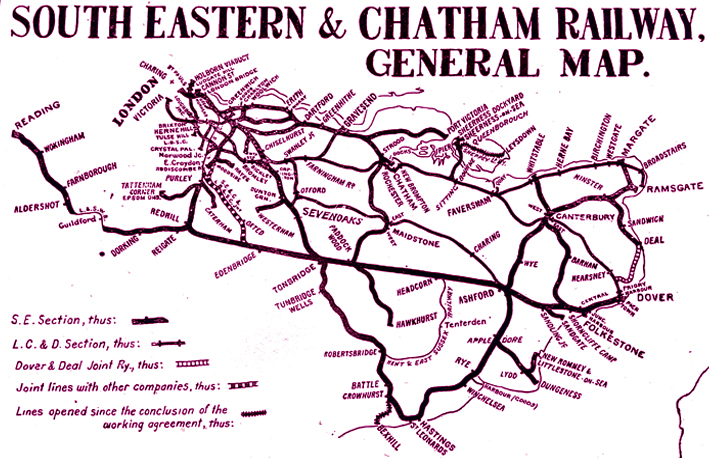

In the early 1820s, railway pioneer William James lobbied for a line to run the six miles from Canterbury to Whitstable. Its benefit, he claimed, would be to relieve traffic problems in the city centre. Work started in 1825 under the auspices of two engineering legends, George Stephenson and, later, his son Robert of ‘Rocket’ fame. The gauge was set at 4ft 8½in, which subsequently became the International Gauge. Opening in 1830, the Canterbury & Whitstable was not the first railway line in Britain, but certainly the first in the South-East. It catered not only for freight, but also passengers travelling in open wagons to the coast; whence its nickname, the ‘Crab & Winkle’. Anxious to secure regular use, the operators set a world first by selling the first-ever railway season-ticket. Nevertheless, the primitive engine, Invicta, was not up to the mechanical challenges, travel was slow, and the line lost money. The South Eastern Railway took it over in 1844.

Crispin & Crispinian (d ca 286)

Crispin & Crispinian (d ca 286)

During Emperor Diocletian’s persecution of Christians in the late C3, two brothers from a noble Roman family, Crispin and Crispinian, fled to Soissons in northern France, where they made shoes and preached to the indigenous Gauls. Arrested by the Roman governor, they were weighted down and thrown into a river. Having escaped but been recaptured and beheaded, they were canonised as martyrs, and celebrated as the patron saints of shoemakers and any number of associated occupations. An alternative version maintains that they escaped to Kent and established themselves as cobblers in a house at the end of Preston Street, Faversham, that eventually became the Swan Inn. An altar was later dedicated to them in the local church. Like St George, they came to be adopted as a particularly English phenomenon, which partly explains Shakespeare’s excitement that the Battle of Agincourt happened on October 25th, St Crispin’s Day. A pub named after them in Strood was frequented by Dickens.

Cromwell’s head

Cromwell’s head